THE ART OF MAKING IT

“Jerry Gogosian, this anonymous entity, is one of the very few places where there’s a cut in the top of the pie to let the air out of how fucking ridiculous the corporate for-profit world has decended, on this thing that used to be bohemian, radical, underground, and actually totally cool because it was those things. ”

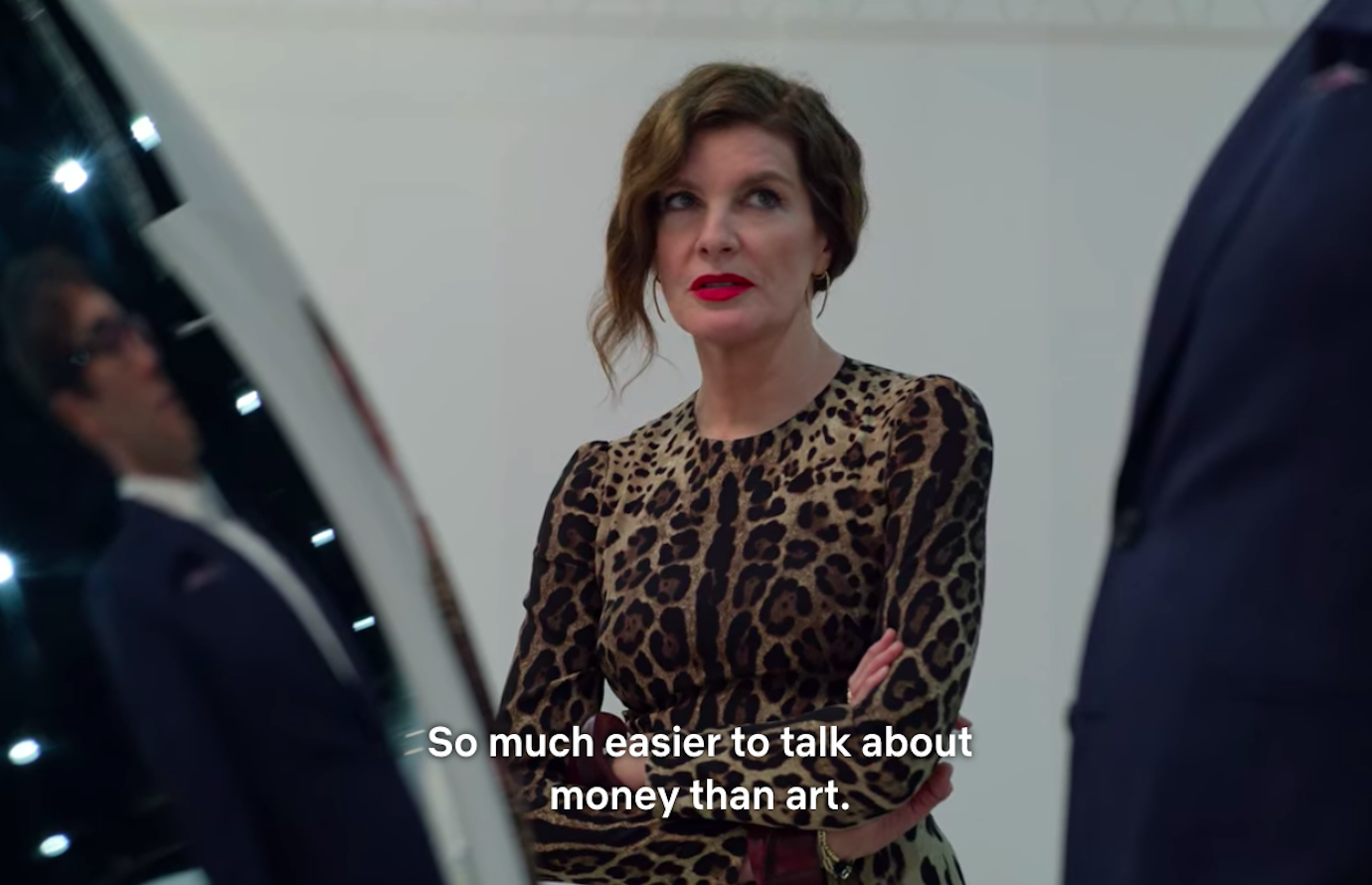

“So much easier to talk about money than art. ”

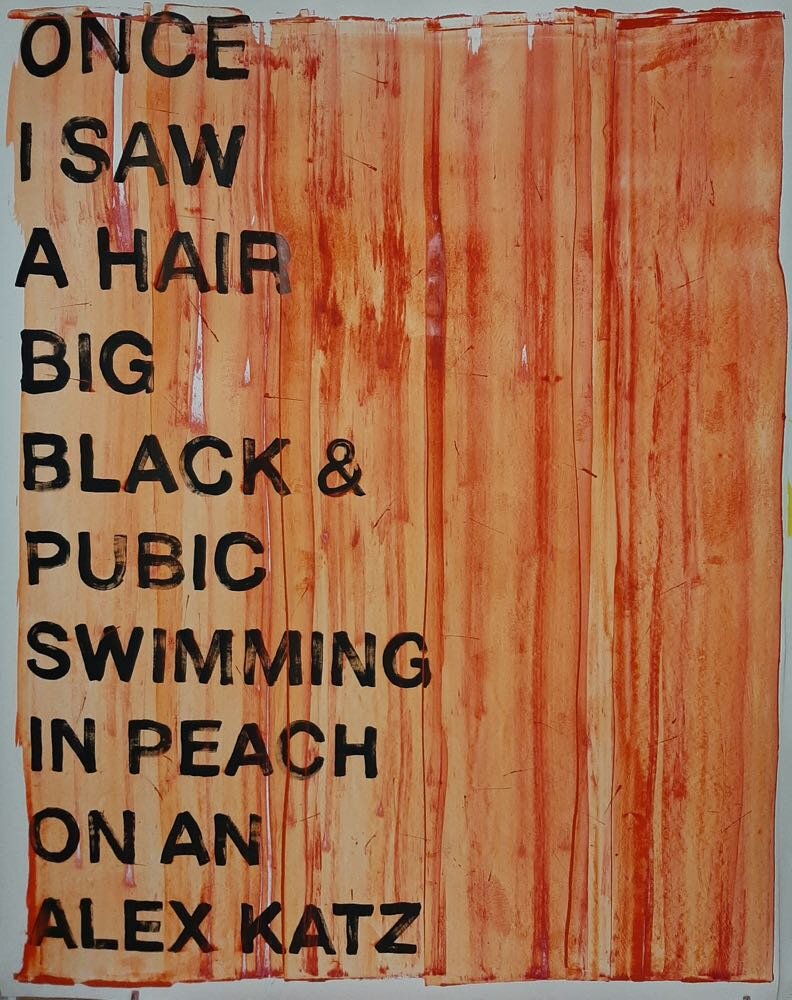

“Art, at a certain point in its history, was thought to be a humanistic study, because of its ability to expand the ideas and the knowledge of the world. It wasn’t thought to be a career. We have to rethink how we deal with a discipline whose main purpose is to produce ideas, not to produce consumer objects.”

“Art is not bought, it’s sold.”

“...commodity fetishism is a definite social relation... that assumes the fantastic form of a relation between things. The value of a certain commodity, which is effectively an insignia of a network of social relations between producers of diverse commodities, assumes the form of a quasi-natural property of another thing-commodity: money.”

“But I love the art world…” (Jerry Saltz)

“I love it too!” (Jerry Gogosian) ”

The Art of Making it is a 2022 documentary on the North American artworld, starring such Instagram-famous artists as Jenna Gribbon and Jerry Gogosian. The “Making It” in the title refers to the career objectives and trajectories of the U.S.-based contemporary artist, from MFA graduate (Yale School of Art) to Mega art gallery (Pace Gallery). It is yet another documentary on artists trying to “Make It” in the big bad artworld of mega art galleries and art fairs. It’s not exactly Velvet Buzzsaw, and not nearly as entertaining, but it’s the same old story told time and again, with new actors to replicate the same advances and withdrawals from the artworld that went before.

This time race, non-profit, education and even Native American art is thrown into the intersectional mix. But their edits feel obligatory not critical. Dealers, and in particular art educators, play the most central and complicated role in the documentary, made complicit and guilty by the art-student debt they perpetuate as actors within university profitable, but student fleecing, MFA graduate programmes in the States. Whereas sociopathic dealers seem to feel nothing at all; their wry smiles curled with knowing rather than emotion. Closer to Velvet Buzzsaw I guess.

Even though most of the artists profiled in The Art of Making It have committed to making it in the artworld, whether via MFA or Instagram, the artist testimonies of how commodity driven or racist the contemporary artworld is, in contrast to the dealer who replies to the question:

“Do you think it’s as tough as it has ever been for emerging artists, or do you think it’s tougher?” with,

“I don’t know, it always seems tough”, is telling.

Nothing has changed or will change because generations of artists are hellbent on trying to make it in this capitalist mode of making and thinking about art. There’s no alternative in their eyes, if the ivy-league education and gallery gatekeepers to the art market is your prize as an artist. In the eyes of the art establishment things haven’t changed, that’s why they are the establishment, hence “it always seems tough”. Artists new and old to the workings of the artworld establishment end up hating it, but also want to be part of it, which makes them hate it and love it all the more.

The narrative arc of The Art of Making It hinges on one artist, Chris Watts, who is accepted to Yale School of Art, presumably aware before applying that Yale is the gatekeeper to Pace, Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth et al. He is dropped from the programme for reasons that are not made clear in the documentary. We are told he “turns up” and “experiments”, but perhaps too fast, too soon. A Yale lecturer corroborates Watts’ testimony when she, after first egotistically listing the artists who went Mega under her watch, admits those artists that made it weren’t the best students, but they understood the market and how to market themselves. It’s all relayed in a matter of fact manner by the lecturer, which makes Watts look either very naive or bitter, especially considering that he must have known what Yale could do for him in terms of marketability when he applied.

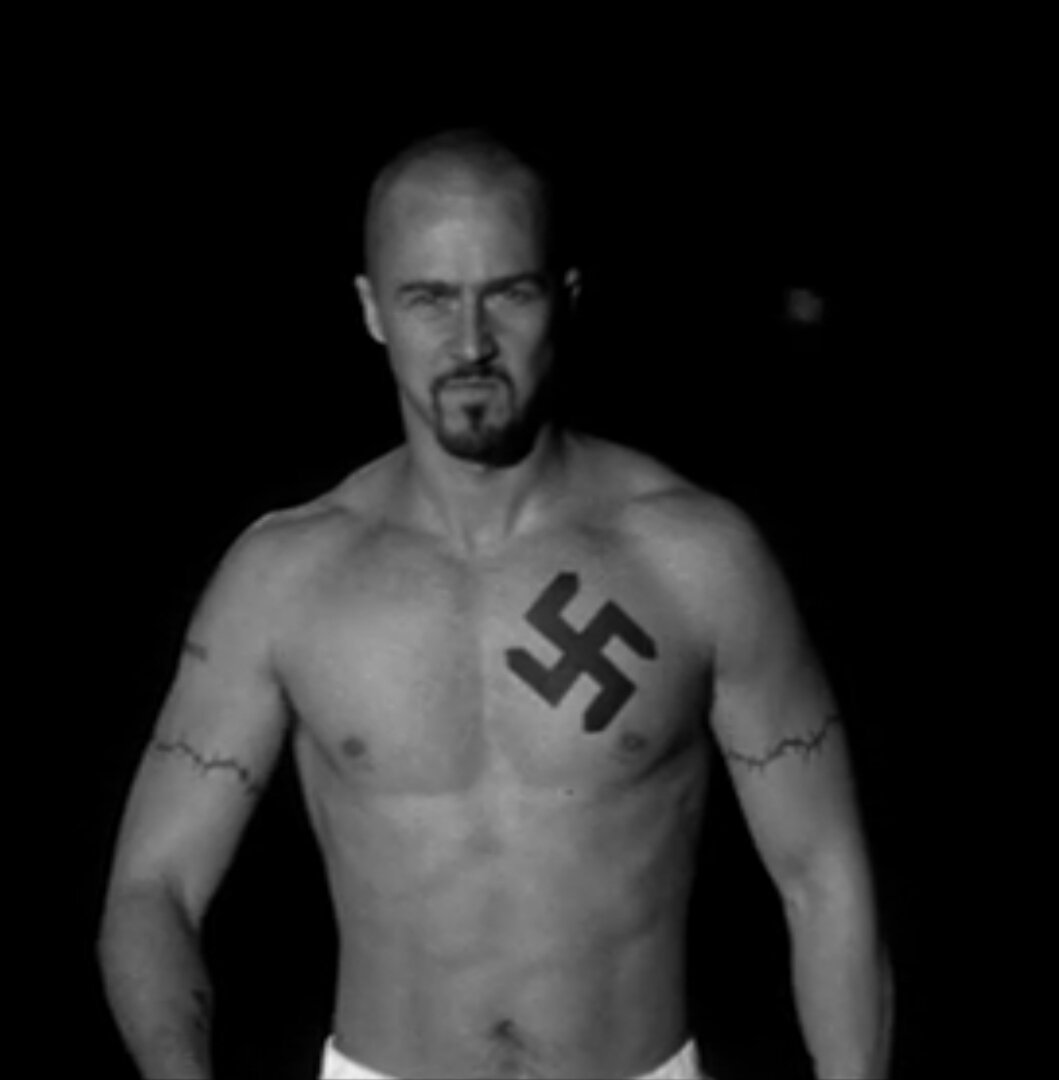

Velvet Buzzsaw, 2019

The artworld described in The Art of Making It is a very distant and different cousin to the one we have here in Ireland. In the first few years of being an art critic, I was in splendid isolation. I was a local art critic. I wrote critically about what was happening around me, specifically in Dublin City. I was cynically productive or productively cynical. I knew what art was in relation to art history, and in terms of the experiences I had in the local art scene, which I navigated week on week through words. Sometimes I went abroad to experience art that was less cerebral or more visceral. I got to know the social patterns in terms of institutional partnerships between galleries and artists, curators and funding, education and galleries. When I noticed an artist could exhibit twice in one year at two spaces in the city, commercial or public, and this was a pattern repeated year on year, I began to question the consensus. (The absolute consensus among dealers surrounding an artist in Velvet Buzzsaw is not rational, it’s viral). When I noticed the rise of the profile of the curator in terms of financial and cultural cachet, I began to question the hiearchy between the art administration (curators) and the artist. But, thinking back, I was getting caught up in a democratic discourse, in which artists, unfortunately, think being an artist is a career, like the curator, a career that could sustain them economically in a country without an art market. “Art is not a democracy” (Gore Vidal).

Jerry Gogosian meme

Writing critically on our little art scene sometimes feels like whipping a puppy into submission. There are no real bad guys or good guys here, just opportunists, careerists and narcissists like everywhere else. Artists are just trying to make art in an art scene supported by public money, funding that helps to get art made but not lives lived. Artists elsewhere are telling me to stop complaining at this point. We’ve got it good. And we do. Those that benefit from it.

But what does a publicly funded art scene look like? Without a private art market artists learn how to write proposals for public funding. It’s a skill, one that is graded in terms of a growing institutional reputation and dependent on a web of the institutional support structures and planning already laid out in advance. Dealers aren’t the only ones who build a stable of artists, so do freelance curators. There is a lot of meaning-making in the public funding process, which can cripple some artists who are in it for the pure pleasure or need. In a sense, public funding feeds back into the institutional architecture of the art scene. It’s a funding feedback loop based on specific criteria and public outcomes. The Irish art scene is primarily a publicly funded art scene, not a privately dealt one — the obverse of New York or L.A. “Annually, U.S. government funding for the arts totals less than $5 per person.” Once again, we have it good.

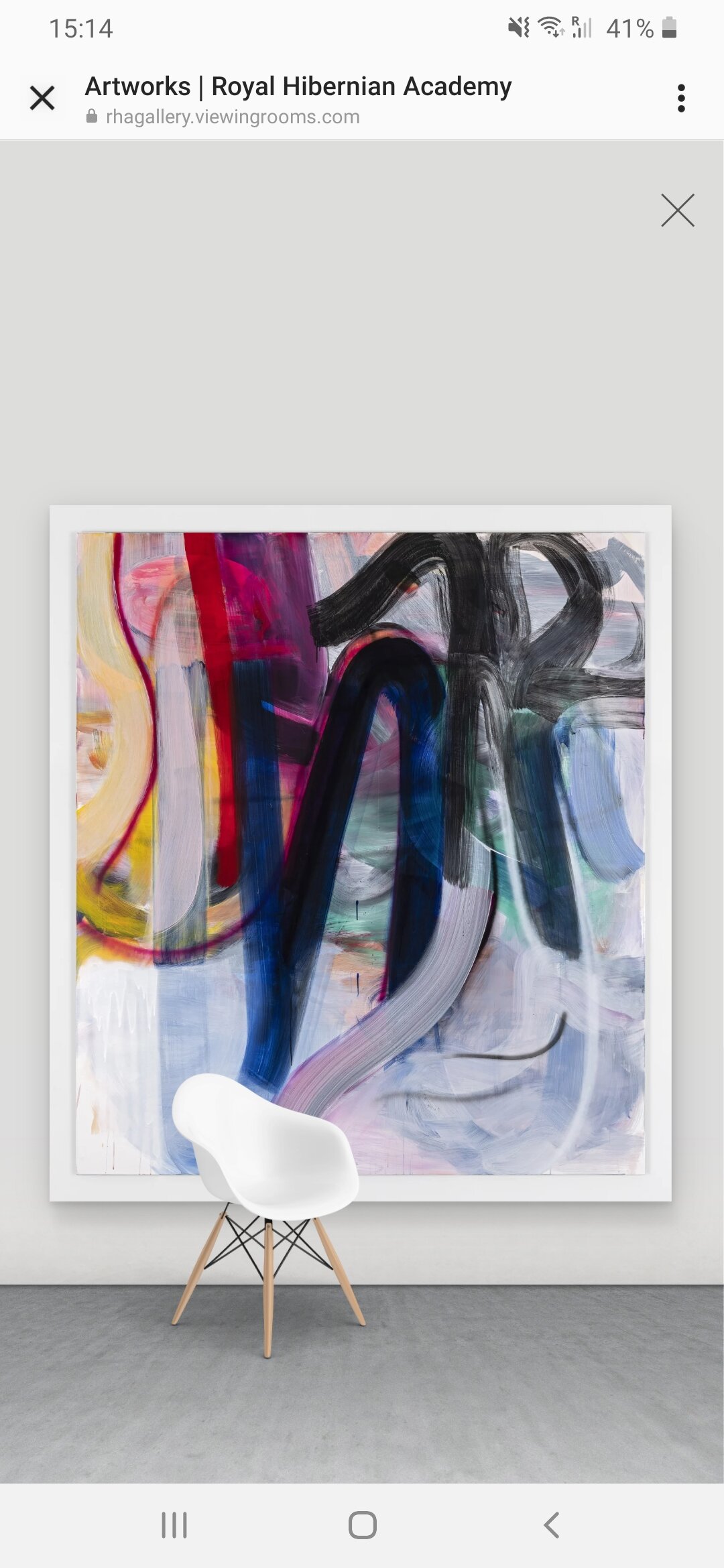

Outside of painting, a lot of the art made under the rubric of public funding can be equated with PhDs in art practice, where artists do a lot of research into marvellous and hidden histories, which manifests into artworks that look nothing like their research, or worse still, look like research. Artists, from art school to public funding, are conditioned by the eminent obstacles of meaning and context. Art is full of meaning here, and it has nothing to do with sentimentality. There’s no dumb Velvet Buzzsaw art. Painting is generally smaller here, and thus more commodifiable, ending up on the handful of commercial gallery walls or basement racks of those few collectors who can afford a basement rack. Failing that, as an image on Instagram. And that’s okay!

A publicly funded art scene is, on paper, a beautiful and fair thing. But critical questions, speculations and imaginings abound. What if a private market of mega galleries and fetishistic dealers suddenly flourished in the city? And those galleries and dealers were as contradictory and complicit with the fluctuating market place of the corporate elite as the ones profiled in the The Art of Making It or Velvet Buzzsaw? Would art made under such capitalist hedonism be more reflective of the world we live in, rather than the marvellous excavations into the past? We have a good art scene, and we have good artists, but sometimes too good. Sometimes the art made here lacks presence and prescience or pure dumb risk.

Yale School of Art.

In The Art of Making It, it is not surprising to hear artist and educator Charles Gaines say the following (even though he is represented by one of the mega galleries Hauser & Wirth, and whose work fetches $100k plus): “Art, at a certain point in its history, was thought to be a humanistic study, because of its ability to expand the ideas and the knowledge of the world. It wasn’t thought to be a career. We have to rethink how we deal with a discipline whose main purpose is to produce ideas, not to produce consumer objects.” Gaines' lucidity in terms of his perspective on what art is and is not is forthright if contradictory. You can imagine MFA students being spellbound by his message. We make ideas to challenge consumption not objects to perpetuate consumption. The artist of today is able to compartmentalise their contradictory roles in the artworld through a cognitive dissonance that accepts rather than denies the conflicts inherent in the mismatch between being an artist and existing in the capitalist realist world of commodities. No matter how rhetorical or dissonant, Gaines is criticising the commodity driven artworld from his role as an educator, not as an artist represented by one of the biggest commercial galleries in the world. Artist and educator Andrea Bowers plays the same role in the documentary, who, after asking a studio assistant what kind of college debt he has — $400k — admits to quitting teaching “a couple of semesters” because she “cannot — literally — strap my students with that kind of debt”.

That is why the interview with Pace Gallery CEO Marc Glimcher is so funny. In that he comes across as someone who was mistakenly rolled out by the Pace board, to then proceed to openly discuss the manipulative mechanics and material hedonism of the architecture of Pace, from the gallery door costing $120 million, which he doesn’t confirm or deny, to the private viewing room where “we give you tequila”. Hilarious. It’s telling that Glimcher chooses poor and tragic Van Gogh’s Letters to his Brother Theo as his favourite book among the hoard of blue-chip artist catalogues that crowd one wall of the white mausoleum. This episode is in high contrast to the non-profit art space The Mistake Room, the director of which reflects on how much he should disclose about the subject of race in the artworld. What might be perceived as Marc Glimcher’s endearing openness, is power at play. He is on top of the pile. Everyone knows what’s going on. We shrug at Jerry Gogosian’s memes because, as curator and writer Helen Molesworth says, Jerry Gogosian “is one of the very few places where there’s a cut in the top of the pie to let the air out of how fucking ridiculous the corporate for-profit world has decended, on this thing that used to be bohemian, radical, underground, and actually totally cool because it was those things”.

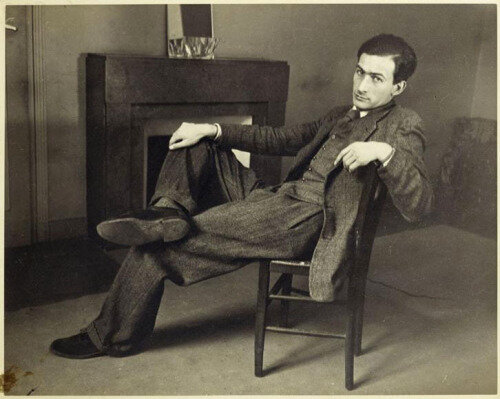

Pace Gallery CEO Marc Glimcher

A critique of Pace Gallery or the Gogosian is as pointless as a critique of capitalism — it goes on. Andrea Fraser, who propagates an institutional critique of the artworld and its institutional mechanisms, is always meta in her delivery, delivered as it is within the very institutions that bear her criticism, while ironically applauding it. Once Fraser said “the artist is an institution” as a corrective to being too literal in terms of big white buildings and black-suited agents in her critique. And yet Fraser is short sighted, or just narcissistically stating her own position as an established artist. Fraser is an artist that has become an institution by being accepted by the institution she critiques: the artworld. Only those artists that become institutions by signing up, or being accepted or sold by the artworld are institutions. Everyone knows the artworld at the levels profiled in The Art of Making It is full of contradictions and corruptions. But so is every other industry at those levels. You just wish it wasn’t the case with art. But business is business.

Helen Molesworth’s nostalgia or mourning for the bohemian art scene of “cool and radical” is also something to be questioned. Is that what it was, cool and radical, rather than the corporate and professional artworld of today? Or was it underground because it couldn’t be mainstream… yet. As Mark Fisher says, Joy Division didn’t want to be identified as a subterranean alternative to the Beatles, “Joy Division wanted to be the Beatles, that’s what made them special.” In other words, Joy Division was competing with the mainstream. They had a bright North to compete with, even though the underground, the cult, would be the dark south from where their music and legacy would spring forth. Subcultures bathe in the shadow of the mainstream audience, a subterranean shadow that depends on the bright lights of the mainstream to colour its deep shadows.

Towards the end of the documentary, in a conversation between Pulitzer Prize winning art critic of the New York Magazine, Jerry Saltz, and Jerry Gogosian (aka Hilde Lynn Helphenstein), both admit to loving the artworld. I get this, even though the artworld is a fantasy from this distant perspective. But perhaps it’s a fantasy for all those invited too. To read too deep into Jerry & Jerry’s outpouring of love for the bad artworld, considering the context, is, in this instance, helpful. It underlines how contradictory and institutionalised the actors (artists, curators, writers) are in the artworld. Without the artworld (as it has been since the 1980s), Jerry Saltz and Jerry Gogosian’s brand of art criticism, which typically focuses on the negative market mechanics of the New York Art World, would never be. Cultural critics aren’t born, they manifest out of a collective discontent with the workings of culture vis-a-vis capitalism. Jerry Saltz and Hilde Lynn Helphenstein are bad artworld products. You don’t pick your Mammy & Daddy. Shit. You don’t even pick your name.

Hilde Lynn Helphenstein (aka Jerry Gogosian)

The Art of Making It opens with Sebastian Errazuriz’s horrible installation of 3D-printed Greek sculptural parodies of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg entitled “The Beginning of the End.” Towards the end of the documentary the disembodied narrator, who adds a few ideological words from time to time, claims “There’s no society without art. It’s not because we like pretty things. I believe it’s because those societies that have been able to remove art, haven’t cared about art, never made it, they extinguish themselves.” It’s a strange thesis, one that places the burden of civilisation on the shoulders of culture. No.

This is an old idea, not a new one. Even though religion has been subjugated by capitalism in terms of cultural patronage, its dissemination and reification in the homes of the elite, culture’s promise, in the eyes of those institutions who value it — the gallerists, collectors, curators, Jerry Gogosian — is to create a foundation for civilisation to live on and them to live off. Jerry Gogosian was crowdfunded to visit the Venice Biennial this year. On hearing this on an Instagram post, one person commented “I thought you were independently wealthy?” Jerry’s reply: “Shouldn't I be paid for my hard work?” Fair enough. In The Art of Making It Jerry Gogosian, in defence of the artworld dealers, says, “we also need people like them”, and then references the Renaissance banking and political dynasty of the Medici Family.

Jerry Saltz with a Jenna Gribbon, from The Art of Making It, 2022.

Culture, at its most civilised best, is to lay to rest in the museum. One commentator in The Art of Making It claims that art is the only thing left after we are all gone; another claims that those societies that “remove art… never made it”. Both claims are inflated and sweeping. Societies or governments have always made choices concerning what art is, what art is not, and what art should represent a society by way of the vagaries of taste, the market or censorship. Adolf Hitler chose Greek and Roman art over “degenerative” art, but he didn’t remove art tout court. Art had a place in Nazi Germany, albeit to propagandise his war machine. Art always has a purpose.

Art is the ticklish subject that unsettles and unnerves the foundations of civilisation; art is not the foundations of civilisation. Yesteryear an artist was accepted, today they are not. Art is undead. Art is not a thing that rises its head from the grave of civilisation to one day, some day, shoulder civilisation in the museum, where is stays still in a contextual paralysis, only to be recontextualised in dusty history books by dustier art historians. The discontented of civilisation have always been artists. Artists are either too soon or too late, premature or tantric. They never really wanted to be in a museum in the first place. All they want is the present, a present that recognises their efforts to shake the institutional foundations that ignore their liveliness until they are dead. Artists don’t tell the future, they tell the present. It’s just that everyone else is in the past. Catch up.

—James Merrigan

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)