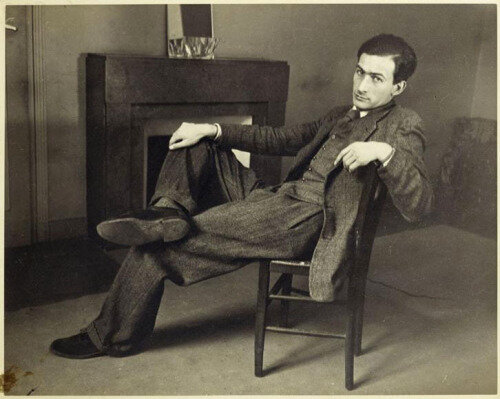

BALTHUS.

Balthus (aged 26), Paris, ca 1934 - by Rogi André (The year he painted The Guitar Lesson, had his negatively received first solo show in Paris, & attempted suicide)

“Balthus has painted some of his most hauntingly impressive portraits of fathers and daughters, of families, of husbands and wives, though it is the daughters on whom his fame rests.”

“The nearer an artist works to the erotic politics of his own culture, the more he gets its concerned attention. Gauguin’s naked Polynesian girls, brown and remote, escape the scandal of Balthus’, although a Martian observer could not see the distinction.”

“It is precisely those harmonies which have become dissonant we want to study in every way we can, for they had a harmonic origin. They changed. We changed. We need to know why.”

YOU sat down tonight, with pencil in hand, & read two books: A Balthus Notebook by Guy Davenport, & Letters to a Young Painter by Rainer Maria Rilke. Both books are from the Ekphrasis Series by David Zwirner Books, the wholesome publishing progeny (including first-time translations to english) of commercial gallery giant, David Zwirner. Your agenda was clear from the outset: to critically explore the paintings of Balthus in relation to his lifeworld, while keeping in mind Sartre's line— “A human person is what he is not, not what he is.”

Balthus, Thérèse sur une banquette 1939, oil on board, 72.7 x 91.9 cm –1939

As you correctly assumed before reading, both books validate & defend the morally controversial artist’s work, paintings that you never had a real taste for in the flesh, but acquired a taste for through reading the downpour of ink that has fallen on the moral nature vs. the aesthetic nurture of Balthus’ paintings. In particular his depiction of adolescent girls, a subject matter that has spawned oil fields, ocean-wide, deep & poisonous.

Far from deep & poisonous, Rilke's Letters to a Young Painter are of the other kind, shallow & sweet, and more about the sender (Rilke in later life) than the addressee (Balthus with a life yet to live). You have always found reading such literary letters by the deceased, perverse, even though you have read numerous, from Susan Sontag's to, in this instance, Rilke's. Contra Sontag's self-conscious & self-critical, Rilke's are buoyant, positive & exclusive in his correspondence with thirteen-year-old Balthus, whom Rilke offloads with advice, enthusiasm & praise for the way in which boy Balthus is emerging into the world as an artist of great repute after Rilke witnessed forty ink drawings Balthus made of his missing & forever lost but remembered cat Mitsou, drawings that Peter Schjeldahl described as “the most precocious art I believe I’ve ever seen, with boldly rhythmic compositions like those in German Expressionist woodcuts and uncanny affinities to Matisse”.

Rainer Maria Rilke with young Balthus and his mother, Baladine Klossowska

Rilke's Letters to an adolescent boy sets the stage & shapes the irony of Balthus' future obsession, adolescence. Balthus was a boy who would become a man with a desire to stay thirteen forever, alongside his adolescent subject matter, his “nymphets”, as Lolita's Humbert Humbert lovingly refers to his adolescent female desire & prey.

After reading William Gass' essay ‘Rilke's Rodin’ you find it hard to wade through this seemingly harmless correspondence between a middle-aged man & a young boy. Maybe it is contemporary culture, or that you are a father yourself, that has you at odds with such an intense correspondence between a boy & a man that is not the boy's father, even though Rilke adopted the on-off role of father in his on-off relationship with Balthus' artist mother, Baladine. That said, Rilke's penmanship is fatherly, or at the very least the poet is acting out what a father might be, or ought to be.

If you know anything about Rilke, whom you have grown to know through your research, you will know that he went out in to the world to discover what it is to be an artist, & “how to live” through the example of the artist. One example Rilke followed word for word was the advice given to him by Rodin, which amounted to the loveless companions of “work” & “solitude”. Rilke would discover through rejection & acceptance that to romance the role of the artist is to end up courting the tragic & pathetic of romance. With Rodin's romanticism tumbling around in his head from his early twenties like the monstrous meat of clay manipulated by the master sculptor, Rilke became the man he is in the Letters to boy Balthus, sacrificing everything to become something beneath the heavy thumbs of a Rodin head massage, which in some part, he was passing on to Balthus as both a blessing & a curse in “how to live”.

Mitsou. Quarante images par Baltusz. Préface de Rainer Maria Rilke. Erlenbach, Zürich et Leipzig: Rotapfel-Verlag, 1921

In your reading you have come to speculate that there were always two Rilke's. You learnt this best from reading William Gass. Gass describes Rilke's prose for Rodin's monograph as “celebratory” & “euphoric” (that’s fine as most artist monographs are celebratory & euphoric). But Gass offsets this verbal euphoria for Rodin's work with extracts from Rilke's letters of the same period to his wife (& child), who he would later abandon to the ‘good life’ of self-critical solitude & the daily grind of work handed down to him by Rodin (whom Gass comically calls a “satyr in a smock” because he never lived up to the advice he handed down to Rilke). Gass describes the twenty-something Rilke as a “poor and alone young man”, documenting the Beckettian bare-boned threads of a Parisian low-life stage, neither idealised nor tainted by the language of romance or religion he performs in the strained heights & hopes he has for the mature art of Rodin & the efflorescence of the boy Balthus.

“They were living, living on nothing, on dust, on soot, and on the filth on their surfaces, on what falls from the teeth of dogs, on any senselessly broken thing that anyone might still buy for some inexplicable purpose.”

Balthus, The Guitar Lesson 1934, oil on canvas, 161.3 x 138.4 cm

There is no doubt that Rilke was a formative influence on Balthus who, throughout his life, was deeply affected & almost surprised by any negative reception to his work, as if nothing but Rilkian praise would do. Following the negative reception he received from his first solo show in Paris in 1934, due in whole to the still infamous painting The Guitar Lesson, Balthus attempted suicide with laudanum. Peter Schjeldahl observes that Balthus “learned to soft-pedal the latter quality” of The Guitar Lesson, intimating the audience, culture itself, softened or censored his expression into what it would become later. So instead of portraying a woman absurdly & violently strumming the naked body of an adolescent girl in plain sight under bright lights minus a voyeuristic veil, we get Balthus hiking dresses of little girls in dark rooms where a glimpse is the world & its origin. To your mind The Guitar Lesson is shocking at first but arrives at absurd & boring quite quickly as shock always does, whereas Thérèse Dreaming (1938), painted four years after Balthus' suicide attempt, soft-pedals into something that is harder to shift from the reservoir of the memory as it dips its toe into the reservoir of becoming more than is depicted within the painting.

Balthus, Thérèse Dreaming 1938, oil on canvas, 149.9 × 129.5 cm

Some opine that Balthus was as innocent & naive to the disjuncture between his lubricious private predilections & those of the culture where he exhibited them in public in 1934 for the first time. Some others have said that Balthus was provoking attention with his subject matter & would continue to do so for the rest of his life. Once again culture is to blame. Judith Thurman writes in the foreword to A Balthus Notebook that when she met Balthus as a young woman he had a “bad boy’s appetite for surprise”. It is a strange comment to make in the context of Balthus, read as accusatory, or worse still, flippant.

The question you have is: is the artist & artwork mutually exclusive when you learn that the subject matter the artist obsesses over is also a subject matter that bleeds into their lifeworld? Further, if that subject matter is morally denatured in both work & lifeworld, how? or should? you separate the artist from the artwork? It is like this: how do you read either Paul de Man or Martin Heidegger after learning of their Nazi affiliation? Guy Davenport is of the mind that Balthus, as a man-boy of “patrician French” (even through the title of Count he wore was a fake, a fantasy) was “aloof of vulgarity”, and furthermore, the artwork is somehow autonomous from the obsessions of the artist:

“Whatever I might know about the artist’s obsessions (which in my case is nothing), that knowledge would remain irrelevant, and the paintings would remain unchanged.”

Balthus, Thérèse 1938, oil on cardboard mounted on wood, 100.3 x 81.3 cm

UP to tonight, you had read primarily American critics on the subject of Balthus & his paintings, from the inwardly agile, poetically condense & brisk Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker, to the outwardly looking, politically brazen & critically sharp Christian Viveros Faune of The Village Voice years (who also co-curated Dublin Contemporary here in Ireland in 2011). Both critics you respect, although Schjeldahl you feel has lost some of his snap & flow via the army of editors & fact checkers that filter the comma-peppered house style of The New Yorker; whereas Viveros Faune wrote his best stuff at The Village Voice &, may you claim, the best critical writing on art in America during the global recession. (You just read Viveros Faune's only collection of writings Social Forms: A Short History of Political Art during the COVID Lockdown, which was also published by David Zwirner Books in 2018.)

Both art critics, & they are art critics in the real sense of the title & role, explicitly call out Balthus as a pervert, no matter how pretty their metaphors peacock fan that shared opinion. Although very different critics in terms of style & critical confrontation with the artwork, their opinion of Balthus in terms of the latent passion or perversion beneath the still & dark waters of his paintings is strikingly similar. Viveros Faune calls Balthus “the fox in the henhouse of the Western nude” (You like that so much you highlight it in pink); whereas Schjeldahl, in one of those prose moments that stop you in your tracks, not because it dances with cat cunning & poise in terms of word & feel choice, but simply because it is direct & unadorned, writes “The man was a creep.”

You notice no exclamation mark after “creep”? And “creep” seems an understatement. It fits the vernacular—adolescence, angst—of Balthus' paintings with Radiohead as the soundtrack. Schjeldahl begins the same article with: “I both like and dislike Thérèse Dreaming (1938), the Balthus painting that thousands of people have petitioned the Metropolitan Museum to remove from view because it brazens the artist’s letch for pubescent girls—which he always haughtily denied, but come on!” There's the exclamation! Schjeldahl also concurred with the Met’s decision to not remove the painting from view. But still you wonder about Schjeldahl's stance in the case of the separation between Balthus’ paintings & his hebephilia.

Schjeldahl, more directly, writes: “Was Balthus a pedophile? His interest, if not lust, didn’t stir before his subjects’ pubescence, but it waned in their late teens.” The writer then does that thing that so many have done in defence of Balthus, even his son, Santislas: “the fabled theme of the young adolescent girl, which Balthus has treated repeatedly, has nothing to do with sexual obsession except perhaps in the eye of the beholder.” Guy Davenport, in A Balthus Notebook, calls this position precisely what it is, “ingenuous”. Schjeldahl continues: “If you can shrug off that tension at the Met, I salute your detachment. I sure can’t. Balthus puts me in two minds, attracted and repelled, in search of a third. He strains the moral impunity of high art to an elemental limit, assuring himself an august, unquiet immortality.”

You imagine Balthus' grave still shuddering beneath falling leaves.

Viveros Faune is less unsteady & tonally less repelled in his critical delivery on Balthus. “Never a formal inventor, this retrograde painter ignored avant-garde ambitions to become modernism’s leading antimodernist, with a twist. The original upskirt artist, Balthus devoted a career to obsessively depicting female pubescent sexuality. [...] Then the writer invokes Robert Hughes & you smile: “Balthus’s trick, in the words of Robert Hughes, was to tension the ‘coexistence between surface calm and predatory desire’.” You remember how good Robert Hughes’ prose is.

A Balthus Notebook is deceiving in title, suggesting either notes by Balthus or on Balthus by another. American Guy Davenport is the note taker. These notes, what Judith Thurman in the foreword describes as “aperçu” (a comment or brief reference that makes an illuminating or entertaining point) are overcome by driftwood references that, in the original edition of 1989, were left beached without footnotes like dead hyperlinks, neither illuminating or entertaining in their referential brevity. The publishers of this 2020 edition have taken it upon themselves to number & endnote all 64 fragments, fragments that sometimes connect discussion & argument, but most of the time feel that nights, months, years have past & the current of the writer's reflections are adrift in an ocean were faith alone will show the way home.

One thing is clear you feel: Davenport is religious in his defence of Balthus. Faith is his compass. You remind yourself that this was written in 1989, a time when art institutions still believed in the privilege of history & reputation in respect to the male canon of art, which was good & great enough to excuse the male artist of his idiosyncratic subject matter in terms of the representation of the female nude, bent this way, that way, & every which way between. Today, however, when dilated eyes replace the winking eye of innuendo in terms of identity politics, gender & race inequalities, Balthus is the most idiosyncratic of all in terms of a particular obsessional subject matter both in painting & life.

Davenport defends Bathus for the very reason he has a “subject matter”, quoting Claude Lévi-Strauss .

“The history of contemporary painting, as it has developed during the last hundred years, is confronted with a paradox. Painters have come to reject the subject in favour of what is now called, with revealing discretion, their ‘work’s….. On the other hand, only if one continued to see in painting a means of knowledge—that of a whole outside the artist’s work—would a craftsmanship inherited from the old masters regain its importance and keep its place as an object of study and reflection. ”

Davenport continues in the theoretical wake of Claude Lévi-Strauss by stressing “music has lost its harmony, literature its resolving plot, painting its skill in interpreting the world”. The more & more you hopscotch Davenport's A Balthus Notebook the more you find that the arguments that are being proffered through a well-read but poorly elaborated encyclopedic referencing pot is not just a sign of a retrograde, religious, sacred, metaphysical or mystical perspective on the arts as something immune from interpretation, judgement, space & time, but immune from morality. The sovereignty of the artist & the work, including Balthus' painted children, are islands unto themselves. “Balthus' children have no past (childhood resorbs a memory that cannot yet be consulted) and no future (as a concern). They are outside time.” Taken further, children are sovereign, painting is sovereign, the artist is sui generis.

“Deviations from iconographic convention register as a transgression”. Davenport’s point here is, if Balthus' adolescents had wings or were planted in the welcome house of religion where moral perversion is forgiven via a Hail Mary & an Our Father—Judith Thurman writes in the foreword that Davenports references are “refreshingly catholic”—then all would be alright. Get this:

“Jesus is naked to signify that he us without original sin, clothing being necessary only after the Fall.”

Or this (which implicates you):

“They are simply misshapen bodies for which Balthus makes a place in order to chasten his (and our) voluptuous taste for the world.”

Portrait of Balthus (rear) and his niece Frederique Tison at the Chateau de Chassy. Photograph by Loomis Dean, France, 1956. Source: LIFE Photo Archive

There is something personal & idealistically eurocentric about Davenport's version of America & its devaluing of childhood. His discussion around Balthus' children is repetitive & searching, which alarms you to speculate that the writer's idealisation of childhood is one that was never experienced in his lifeworld but imagined in fantasy, in dreams, in Rousseau, in Balthus. Printed on the back cover of A Balthus Notebook is the question: “Is the dividing line between nature and culture the imagination?”

Davenport's notion that painting has lost its skill, implies that he thinks that the sovereignty of paint unto itself rather than its material disappearance under the illusive properties of the realistically painted image is a modernist & secularised reduction of what is a “philosophical” difference… “even a religious” difference between Balthus & the “reductio ad absurdum of Pollock”. Davenport would take issue with Viveros Faune's notion of a lack of formal invention in Balthus. Davenport continually defines & celebrates Balthus as a “naive painter”, self-taught & outsider to the train of modernism that overtook culture in the twentieth century to make artists into passengers of the cult of the new, the progressive & the market.

Balthus (to Davenport's mind) “remained in the distinguished category of the unclassifiable, like Wyndham Lewis and Stanley Spencer. If modernity ended in trivialising its revolution (conspicuous novelty displacing creativity), it also has a new life awaiting it in a retrospective survey of what it failed to include in its sense of itself.” It is a remarkable statement, one for the ages, as it reflects our own time in the retrospective celebration & validation of those artists, outsider & women, who did not measure up to modernism's image of itself. David Zwirner Gallery, a half-billion dollar a year company, has held several outsider-art group & solo shows, Bill Traylor being one, whom, coincidently, is mentioned by Lucas Zwirner in his afterword for A Balthus Notebook.

Balthus. André Derain 1936, oil on wood, 112.7 x 72.4 cm

You wonder how you would feel now standing in front of a Balthus like Theresa Dreaming or The Guitar Lesson or André Derain (above) knowing what you know about Balthus bi-proxy his paintings & later exhibited Polaroids of adolescents; or after having kids who are not yet Lolita's age or Balthus' “passion” (Schjeldahl) or perversion (Viveros Faune). And not to forget being watched looking at a Balthus painting, even if the pretence of history within the art museum shelters you from being judged a beholder of the tensions to perversion that populate the sharing eyes of a voyeuristic culture—watching sex on TV with Mam & Dad. Davenport writes that the artist “must give us new eyes. He must educate our sensibility.”

So how does Rilke's Letters to a teenage Balthus & Davenport's Notebook on Balthus educate your sensibility. You know as a young painter you would have aesthetically lapped them up like Balthus' cat laps up milk from a saucer. You suspect the subject matter would have been beside the point in your attraction & attention to technique. Your eyes would have poured over Balthus' technique (especially post the rigid & crude The Guitar Lesson)—painting technique in the eyes of a young painter wanting to paint the world the best you could is all there is. You would have related & recognised the awkward poses as those of your young self. You cannot imagine being aroused by the subject matter of Balthus' paintings as a teenager, as they are, from the viewpoint of you the adult, warped fantasies that fail to scale the unbridgeable gap between childhood & adulthood, innocence & experience. The negative spaces between boney elbows, knees & toes you would have unconsciously assimilated as a future formal strength in your own work, but the objects & bodies that offset those negative spaces would have just appeared strange & haunting & aggressive to your naive sexual sensibility. Painting, as Davenport writes, may indeed be—the seen, but hidden eyes still abound like live insects in the paintings of Balthus.

James Merrigan is an artist & critic living in Waterford City Ireland.

A Balthus Notebook. By Guy Davenport. Contribution by Judith Thurman. Afterword by Lucas Zwirner. David Zwirner Books. 2020.

Letters to a Young Painter. By Rainer Maria Rilke. Introduction by Rachel Corbett. Translated by Damion Searls. David Zwirner Books. 2017.