MADDER LAKE ED. #12 : TOWARDS NOSTALGIA

EDITIONS

“IN APRIL 1970, Gregory Battcock appeared in his underwear on the cover of Arts Magazine, the publication he would briefly lead as editor some three years later. […] But Battcock’s appearance on the cover... is perfectly consistent with his writings within its pages—it epitomises ‘criticism without apology’, as he once described the writing of Village Voice critic and lesbian activist Jill Johnston.”

If it hasn’t happened already, one day it will. You will start to revisit the past with more frequency, becoming a graduating ghost of the present. As you jump back and forth in your joyous and tragic recollections like some ageing Time Lord, the present will become more ghostly, the past more concrete, rising up above your in situ indifference like a colossal monument basking in the glorious light of hindsight.

I've been Time-Lording it a bit lately. It's a symptom of ageing, but also a side-effect of covering art history across two curricula. To combat the adverse effects of art-history-time-travel I pick some favourites to offset the usual suspects within the canon of art history to cover the course bases and my biases. Through the process of resurrecting such brilliant and sometimes cruelly obsessive and egomaniacal artists I start to measure their artworld-shattering moments against the dancing pebbles from the little earthquakes of the present. The past wins every time. The present hasn't become the bejewelled memory of some ageing Time Lord in the future.

The early days of being a Time Lord you already begin to glimpse ghosts as the present becomes a Bells Palsy half-world of mushy decline. And the more and more your memories decline the more and more precious and false your memories become; their cavities filled with cubic zirconia to disguise their decay.

Maybe it was a case of being snowed in these last few days, but the image of art critic Gregory Battcock sitting and smiling on an ocean liner on the front cover of Joseph Grigley’s Oceans of Love: The Uncontainable Gregory Battcock greeted my deepest cabin fever from the warm bookshelf.

I'd been waiting for the right time to write something on Battcock, who has become a hero of mine ever since making an unplanned visit to Marian Goodman Gallery London in the summer of 2016, where, to my surprise, I found myself lost in the ‘Gregory Battcock Archive’ for more than an hour. The cover image that jolted me out of snow blindness is of Battock en route to somewhere planned, Leningrad, in 1973. He’s 36 — seven years later he would end up dead, stabbed 102 times by his Puerto Rican “houseboy" in an unsolved murder committed on Christmas Day in 1980. But before all that, Battcock, at 36, had already published several art anthologies in his twenties, had a job in academia and held the editor’s job at Arts Magazine, albeit only for a year. It all sounds nice and secure. But there were two sides to Battcock: the official side was the means to support his leanings toward an underground side, where he experimented with confession and gossip in relation to art criticism, and indulged in his other loves and lusts: sex, food and cruise liners.

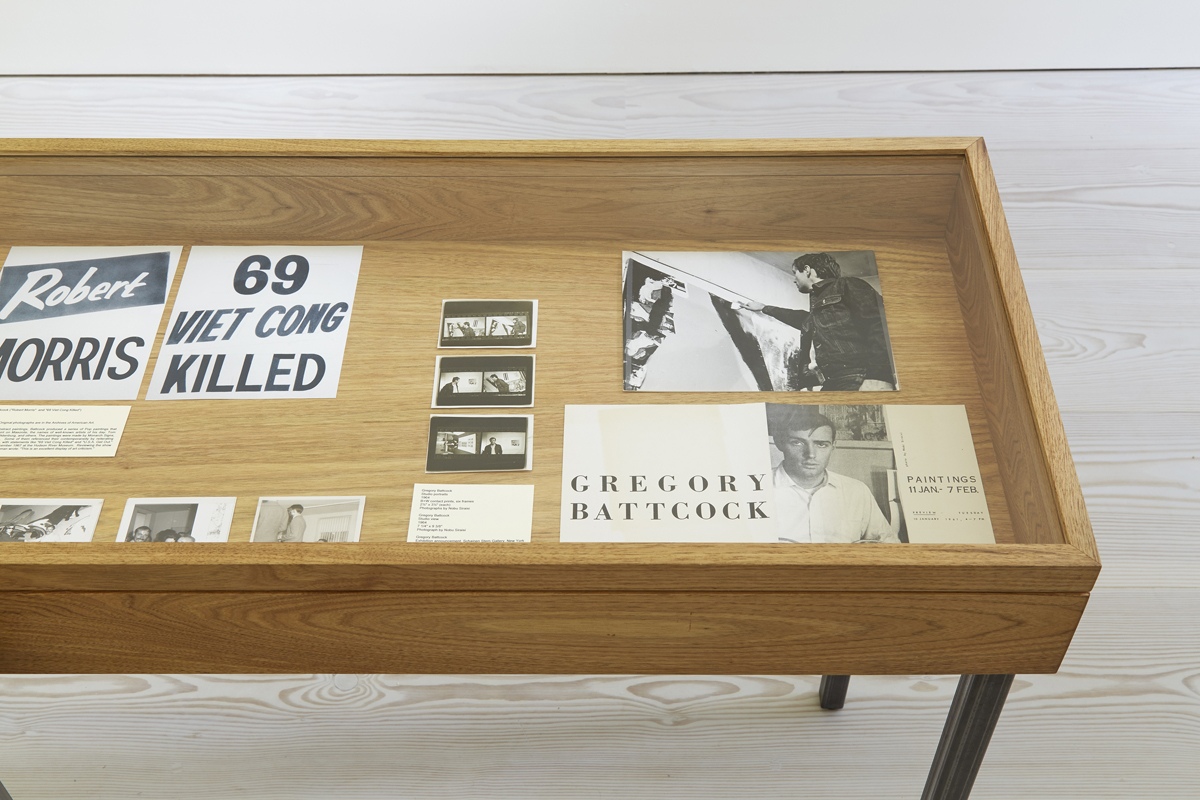

Joseph Grigely (who solo exhibited on our own doorstep at the Douglas Hyde Gallery Dublin in 2009) came across Battcock’s possessions when the “Shalom” storage company was evicted from a building where his studio was located in 1992. Grigely was 36, the same age Battcock is on the front cover of his book. Grigely had just returned from the “beautiful White Mountains” (the snow metaphors keep coming) to discover Shalom gone and, amidst a paper hoard of scattered and shattered lifetimes, seven boxes (originally 48) that belonged to “Gregory Battcock”. Being an art history professor Grigely recognised the name immediately, especially his “well-known anthology on Minimalism”. It was a match made in archive heaven. But it would take 20 years or more before Grigely would get around to writing the book and exhibiting the archive at the Whitney Biennale in 2014.

Eating Too Fast is a 1966 Andy Warhol film made at the Factory. It was originally titled Blow Job #2 and featuring 26 year old art critic and writer Gregory Battcock.

What Grigely discovered in the paper trail was a very complicated man. Nine years younger than Andy Warhol, Battcock graduated from the Warhol Factory, starring in a couple of his films, and was even ‘commissioned’ by Warhol to travel to Paris with fellow critic David Bourdon to take some photographs enjoying themselves in the look-don’t-touch Andy Warhol way. And it is through these ‘other’ adventures, usually on cruise liners, that the real Battcock is revealed to us in intimate detail. There’s his ‘Cruising’ diaries, where he explicitly details his sexual encounters with other men; his gossip columns, what he called his “yellow journalism” for Gay and The New York Review of Sex and Politics; and his self-published, self-edited and intentionally absurd zine Trylon and Perisphere. From paper to paper, alter-ego to alter-ego, officialdom to underground, Battcock utilised multi-personas and platforms to perform without fear of judgement or retribution by what he believed to be an increasingly moralising, market-led artworld. So nothing’s changed.

Alice Neel, Gregory Battcock and David Bourdon, 1970, oil on canvas.

But Battcock was as uncontainable as he was unpredictable. He didn't view art criticism as suppliant or supplementary to the art object, he believed it could breathe on its own. Crigley writes: “His reviews and essays published in Gay and the New York Review of Sex and Politics unmade and remade the genre of ‘criticism’ in a way that made the mainstream criticism seem as staid as it did unambitious. [...] As his friend, the essayist Jill Johnston, wrote after Battcock died: ‘He was a failed artist whose sour grapes were entirely original, and so absurd, such a parody on themselves, such a parody on this parody, etc. (the last hardly recognisable), that they had been dislodged from their point of reference and were functioning on their own — an art form too detached and intelligent to be called criticism.”

If the readership wouldn't listen or the mainstream publishers wouldn't publish, Battcock would find a readership and a publisher that would. His stint as editor for Arts Magazine was short-lived because sometimes he let his underground idealism bleed into his professional life. Grigely illustrates this bleed in an exchange between critic John Perreault and Battcock in 1970:

“Perreault: You write for nefarious publication the New York Review of Sex and I understand this has gotten you into several difficulties.

Battcock: It has. Into quite a few difficulties, as a matter of fact people are very jealous.

Perreault: What do you mean?

Battcock: Well, they try to put all kinds of pressure on me to stop writing. My publisher, my university, my colleagues. They all do this under the guise of reputation and scholarship. All those questionable values.

Perreault: Yes, which you pay no attention to at all.

Battcock: Yes, I do pay attention to them. The more pressure I get for writing in that paper, the more determined I am to continue writing for it. Very likely I would have stopped a long time ago if I hadn’t met this extraordinary hostility.”

Battcock sought out and fostered critical vitality in others too, such as in the dance critic for the Village Voice, Jill Johnson, who “got Battcock in a pickle with an essay she wrote for him [as invited Editor of a special issue ‘Notes on Women and Art’] for Art & Artists magazine in London in 1972. [...] Johnston’s piece began”:

“Male gallery dealers suck cockFemale gallery dealers suck cockMuseum people all suck cockCollectors suck cockArt appreciators suck cockArt historians suck cockArt critics suck cockArtists suck cockThe art world sucks cock.”

But Battcock is not just embodying sex or sexuality in his writing. What is so refreshing about Battcock is, he didn’t define art criticism as this or that, definitions that have subjugated art critics to self-righteous injunctions over the last decade. “[Gregory] Battcock, like many other critics of his era, and unlike the majority of critics in our own — was more interested in broadening communication than in defining it.” (David Joselit)

There is real humour and invention in Battcock’s subterranean and sea adventures. Battcock loved — I mean LOVED — cruise liners, perhaps for all the reasons we might hate them (as outlined in gorgeous detail in David Foster Wallace's ‘A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again’). He had this whole take on a future “shift in aesthetics from attention toward the ["tyranny of the art object”] to attention toward the receiver”. His “aesthetics of transportation” included an archive of unrealised curatorial projects based on cruise liners, cruise liner museums, etc.; not to mention his “Humourous Artist Statements” that anticipate London art collective BANK’s parodic intervention in artist statements by decades.

Robert Mapplethorpe's two invites for The Perfect Moment, which opened at two spaces in 1988: Holly Solomon exhibited the commercially viable portraits and flowers, while the experimental space The Kitchen exhibited the sex pictures.

Battcock’s life as a critic and his relationship with the New York art scene is best illustrated through Robert Mapplethorpe's two invites for The Perfect Moment, a dual exhibition that opened at two spaces in 1988, when Holly Solomon exhibited the commercially viable portraits and flowers, while the experimental space The Kitchen exhibited the sex pictures. Dualistic tendencies are common in the artworld as a kind of survival kit, leaving one alter-ego to take the brunt while the other blossoms.

Grigley’s archiving is in no way academic in book or exhibition form. At times it feels like a twenty-something art graduate is recounting the details of Battcock’s life rather than a fifty-something art history professor. There is a youthful vitality to the accounts, as if Grigley wants to believe that Battcock’s world of risk over rote is somehow possible again, if only today’s critics would take notice of the possibilities that Battcock lived and wrote on rather than theorised on. (Or maybe that's just me.) But what you do get from today's critics in their reviews of the Gregory Battcock Archive is romantic puzzlement over why Battcock’s unmaking and remaking of the genre of art criticism, and not defining it as this or that, is not explored more by today's critics, who vie for the attention of one audience. The last time I was excited by writing on art in this country, writing that hadn't been polished and preened to an inch of its life, was Hilary Murray's gossipy and confessional online blog entries for Circa Magazine at the height of the financial crisis. But vitality like Battcock's doesn't last: its nature is not to survive.

Cheers Gregrory Battcock and Joseph Grigley for the resurrection.

*Oceans of Love: The Uncontainable Gregory Battcock, by Joseph Grigley (Editor, Preface, Introduction), Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, 2016.

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)