FROM KANYE WEST TO ARTHUR JAFFA AND BACK

“I’m acting now, playing a role”

“When a giant looks in the mirror, he sees nothing ”

“Amen”. The last word spoken by the co-director and narrator, Coodie, of the 4-hours 30-minutes Kanye West documentary, Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy (2022). So why, at the Douglas Hyde Gallery Dublin, have I ended up in Amen and “Ye” Country?

Answer: Arthur Jaffa. Specifically, Arthur Jaffa’s 7-minutes slice and splice of black lives appropriated in a jittery matrix of emotions and mess of racial consciousness. Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016) is a compilation and complication of moving images edited against the unifying music of Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam. Taken from his 2016 Album The Life of Pablo, what one reviewer described as a hollowed-out gospel song within a “maximalist” album, the “Pablo” in the album title refers to the three Paul’s (Pablo Picasso, Pablo Escobar and Saint Paul) and perhaps the things they represent: Art, Gangster and God. As we will see (and as we are seeing in the unfolding media scrum surrounding Kanye West), it’s very, very, very complicated.

The critical reception to Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo seems to correlate and complicate its relationship with Jaffa’s appropriation of Ultralight Beam in Love is the Message, The Message is Death, and Jaffa’s film oeuvre as a whole. I arrived late to the brilliance of Jaffa’s work, in the months subsequent to the artist being awarded the prestigious Golden Lion Award at the 2019 Venice Biennale. It was in Venice, and the film that made Jaffa’s name at Venice, The White Album, that I first experienced his brilliance as an editor, or what Kanye West was dismissively named before becoming a rapper in the minds of his peers, a producer.

On entering the room wherein Jaffa’s The White Album was screened in Venice, we were met with contrasting belly laughter and cooed offence — thunder and lighting. One person was arguing with another over their inappropriately misplaced laughter. Like bullets, stray laughter can harm. Over the 30-minutes duration of film, the two became heated, but remained UFOs in the scattershot light and dark of Jaffa’s projected film. Huddled among all those people, those strangers, some there because Jaffa won the Golden Lion, others there by circumvented accident (as we were) was invigorating. It was like we had stepped into a film, a delta of people reaching from seats to floor, touching the walls, screen, each other, us. A raft of reachers: Géricault.

The opposite is true of the Douglas Hyde Gallery’s screening of Jaffa’s earlier and much shorter (7+minutes) Love is the Message, The Message is Death. On my watch, it felt like the gallery had been evacuated of all people and artworks: a giant screen left on, audio-visual crates and gear waiting in the aisles for the End. No invigilator. A table full of books on Race standing forlorn where former Paradise was empty. Bench. Bench. Bench. I stood. Seemed inappropriate to sit, like laughing in Venice.

Outside a raft was needed as Dublin City was adrift in thunder and lightning without a silent buffer (crackle-boom); inside Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam shined and sutured:

I’m tryna keep my faith

We on an ultralight beam

We on an ultralight beam

This is a God dream

This is a God dream

This is everything

This is everything

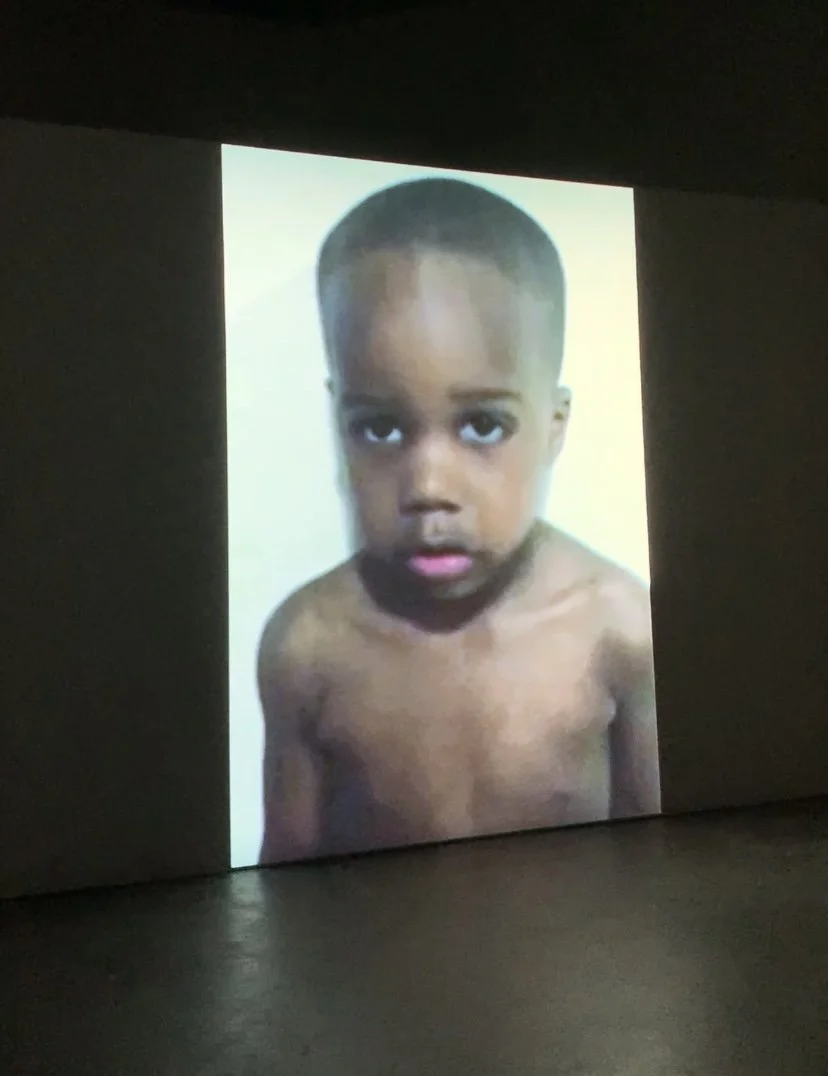

It is gloriously whole: visuals and beats. This dissonance, what one commentator calls “affective proximity”, is what Jaffa is celebrated for in the artworld. When both Jaffa and West, or West and Jaffa come together in Love is the Message, The Message is Death at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, dissonance rhymes. It’s a cavernous chop shop: Kanye’s chopped-up gospel beats against Jaffa’s chopped-up clipped clips. The screen is huge; cater-corned . Large, flat wall speakers, minimal square and grey, but ever present. The gospel according to Kanye brings bass drum, reverb, satanic inverse organs and choir to the panoply of Jaffa’s moving images, that suck and move and sample under the weight of their motivation: to affect through the close proximity of their diametric emotions. Once again, it is gloriously whole: joy abuts injustice; the everyday sparkles in the light of the extraordinary; and in terms of art-making and art, originality comes under the permissiveness of appropriation. And yet I am left with questions: Where does Kanye West end and Arthur Jaffa begin in Love is the Message, The Message is Death? Or does it matter?

Kanye West, The College Dropout, 2004; Kanye West, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, 2010 (censored cover); Kanye West, The Life of Pablo, 2016.

Afterwards, I went home and listened to several Kanye West albums. I had left the gallery with Kanye on my mind, not Jaffa. I wanted more. I got more.

Later I learnt that, as in both Jaffa’s visuals and Kanye’s beats, there was also a dissonance in the reception to The Life of Pablo on its release in 2016. Not just in opposing reviews, but within single ones. Rob Sheffield wrote presciently that “West just drops broken pieces of his psyche all over the album and challenges you to fit them together.” Jon Caramanica opined West "has perfected the art of aesthetic and intellectual bricolage, shape-shifting in real time and counting on listeners to keep up", concluding "this is Tumblr-as-album, the piecing together of divergent fragments to make a cohesive whole”. Ray Rahman (with the conflicting addendum “glorious whole”) criticises and commends “an ambitious album that finds the rapper struggling to compact his many identities into one weird, uncomfortable, glorious whole.”

It is this dissonance and dialectic between Jaffa and West, visuals and beats, that brings up the question of appropriation. Where does appropriation end and art begin? Did Marcel Duchamp just fall in love with the urinal, like perhaps Jaffa fell in love with Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam? As I have. Is appropriation in art just a love letter rather than a conceptual conceit as Duchamp would like us to believe. Lest we forget “Appropriation in art and art history refers to the practice of artists using pre-existing objects or images in their art with little transformation of the original.” It is the “little transformation of the original” in the definition that sticks. If more than a “little transformation of the original” takes place in appropriation, does that mean the art is void? Is there a limit to too much or too little transformation? Like Duchamp signing the readymade urinal “R.Mutt”? If he signed it ‘M.Duchamp’ or a variation thereof, would that have been too little or too much transformation? If he signed it in red instead of black? What then? Too much or too little? The bottom line in appropriation must be the retention but also subjugation of what went before in the original. Obviously the artist who appropriates has to survive the appropriation, to use and repurpose, but also overcome the object or image appropriated. Or does the artist need to survive their appropriation of the other?

I don’t think Arthur Jaffa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death survives without Kanye West. In other words: I can imagine listening to Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam in the Douglas Hyde Gallery with its loaded beats and lyrics addressing faith and race, but I cannot imagine looking at Arthur Jaffa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death without Kanye. It may be a dumb negation in respect of Jaffa’s mode of art-making, dependent on editing and curating appropriated content, but bear with me for a dumb beat.

I listened to Ultralight Beam countless times after my experience at the Douglas Hyde Gallery. I became obsessed with it: entranced. The dissonance, pacing and timing. The sampling of the child exorcising the devil and imbibing God with grandma’s overheard validation is both medium and message: Art. These are all the things that Arthur Jaffa’s work, especially The White Album, is acclaimed for, and aspects that speak volumes in Ultralight Beam and Kanye West’s work at the height of his creativity and production.

There is another thing that should be critically confronted, and that is the current media storm surrounding Kanye West’s very recent anti-Semitic comments on social media, proclaiming on Instagram just weeks ago, his interest in “going death con 3 On JEWISH PEOPLE.” When experiencing Jaffa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death, which is so dependent on Kanye West’s formally integrated Ultralight Beam, can we separate out Kanye from the experience of the artwork, especially considering the fundamental message of both Jaffa’s and Kanye’s work is a criticism of racial prejudice? This is an affective proximity that may be too much for some people to bear.

The Kanye West documentary Jeen-Yuhs, where I started this very speculative criticism, is about survival: surviving being black, surviving prejudice, surviving peer dismissal, surviving mo’ money mo’ problems, surviving God with a capital G, and surviving Kanye West, which continues apace with his antisemitic remarks, and follows years of questionable affiliation with Christian and right-wing policies regarding pro-life, pro-Trump and criticism of Black Lives Matter movement’s over-emphasis on black trauma in terms of history.

Against this often times absurd, dangerous and painful discourse propagated by Kanye West, I am left with the genius of his music in the Douglas Hyde Gallery, and the enigmatic back story courtesy of Jeen-Yuhs. Such as the scene in which Kanye walks into rap royalty’s Jay Z’s Roc-A-Fella Records, slots his CD into the office stereo, and raps along to the beat, to be ignored, and then to do it again in the adjoining office. The ambition, self-belief, nerve, it’s wonderful to witness. (Even though this self-belief was to become absolute belief – “Jesus Walks”.) And then there is the death of Kanye’s mother, Donda, at the height of her son’s fame. The one who told him that “When a giant looks in the mirror, he sees nothing”. It was all forecast or feared by his mother; “Ye” the antagonist was born on the day of her premature passing at 57.

This notion of affective proximity is not just performed in Arthur Jaffa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death, or Kanye West’s music, lyrics or his recent interview on the Lex Friedman podcast aired yesterday, or Coodie’s and Chike’s documentary Jeen-Yuhs. Affective proximity is also performed in the sense that a Kanye West song is being played in a public gallery. And not just for obvious reasons regarding copyright, which usually prevents visual artists from appropriating the music by artists of Kanye West’s market stature. But just because it is Kanye West being played on full dial in the Douglas Hyde Gallery. I can’t help but enjoy it. Like the affective proximity of the thunder and lightning outside, amidst the high-hat rain, love and hate, the beats and beef goes on. In the end, when all is said and done, it all fades to black.

Appropriation, at its best, is when the artist disappears under the cultural weight of the material appropriated. Arthur Jaffa has to disappear for his appropriations to be heard and seen. But sometimes those appropriations are so loud that they silence everything in their wake. Listen. See. —James Merrigan