DAMIEN FLOOD: TODAY

WHEN I think of archaeology and anthropology, I think of three things: digging, death and Damien Flood’s paintings. Over a decade ago I critically called out Flood in my first text on his paintings, The Corrupt Geologist and the Awkward Coroner.

Extract: “Damien Flood's paintings look like they were made by a corrupt geologist. He is knee-deep in browns, drips, rainbows, islands and mountains, that either shadow or seem to be in the act of swallowing everything whole around them. His daily painting routine is a process of excavation, when several layers of painted horizons are either covered over or dug back up, using the awkward relationship between chance and intent to uncover a corrupted space or form.”

That was 2011. Later, in 2020, in the monograph essay The Mythology of D & Me, I wrote: “Words, words, words, and paint; the dumb reality of words and paint.” I have written and spoken many dumb words about Flood’s paintings. Experiencing his work today (Wednesday 16th November, 1pm) at Green on Red Gallery Dublin, I wanted to experience them as they are, without words, without sublimation — solid to gas. But here I am. That says something that I won’t understand until after today.

Today I thought about civilisation. That thing we proclaim when emerging from the wilderness after being lost for days in said wilderness. The shout of CIVILISATION! as we exit the woods, dirty and almost dead, is elevated to saviour in this context. But what are we really shouting at the moment of least hope followed by gracious relief.

Detail.

Civilisation, outside the context of despair and relief, is a society that has reached a mature and highly developed state of development in terms of human behaviour, technology, and what Michel Foucault might call “the administration”, or with sunshades and bondage gear on, “the police”. Culture is generally included in the definition of civilisation. And yet I like to think of culture as the thing that questions and criticises the foundations of civilisation, while also keeping in mind that the final resting place of culture will be, for good or ill, the tomb of civilisation, not the wilderness of culture. To my mind culture exists in efflorescence not civilisation. Civilisation is culture all grown up, secure in its own legacy. Sean Scully thinks he and his paintings are civilisation. He may be correct.

Today sunlight flashed the space like the most shameless streaker. There was a feeling that the world within and the world without were not so separate, as the excoriating sunlight shed the space of a softer skin. Revealed: the pockmarked walls; the patched-up floor; the rusty brown-orange scrawls on the ceiling, as if a metal bird had tried and failed to escape. SQUAWK! More and more I believe the setting for art determines its capacity to be more than its individual parts, more than a showroom or window display for the penniless artist, looky-loo consumer or loaded collector.

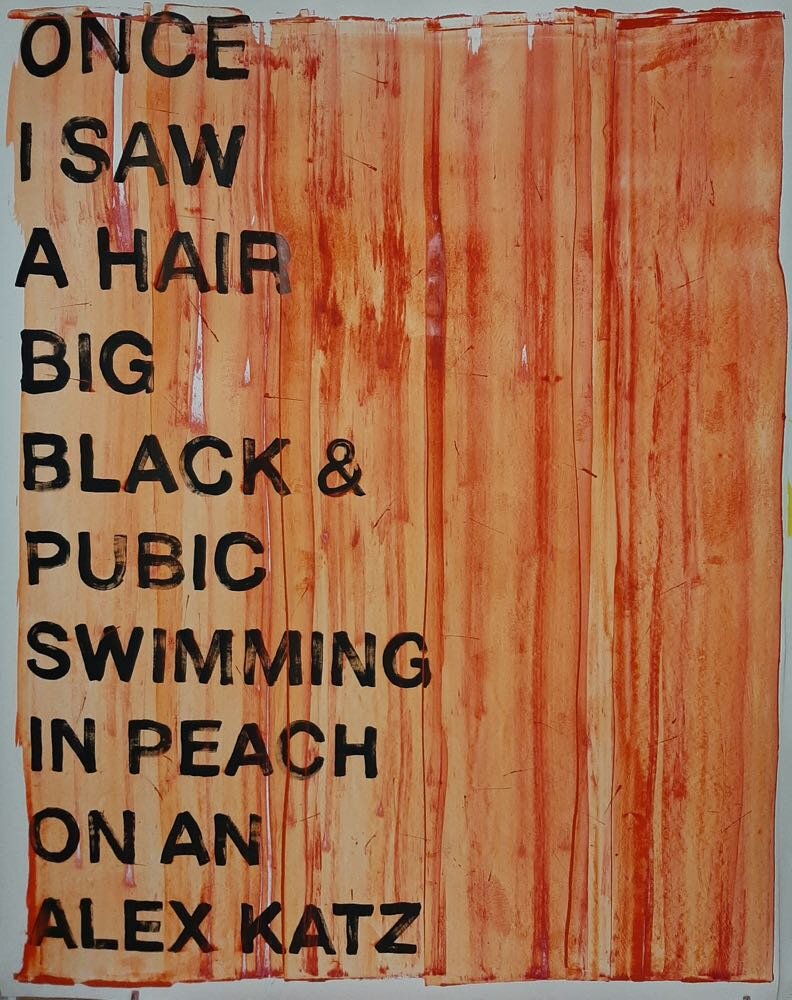

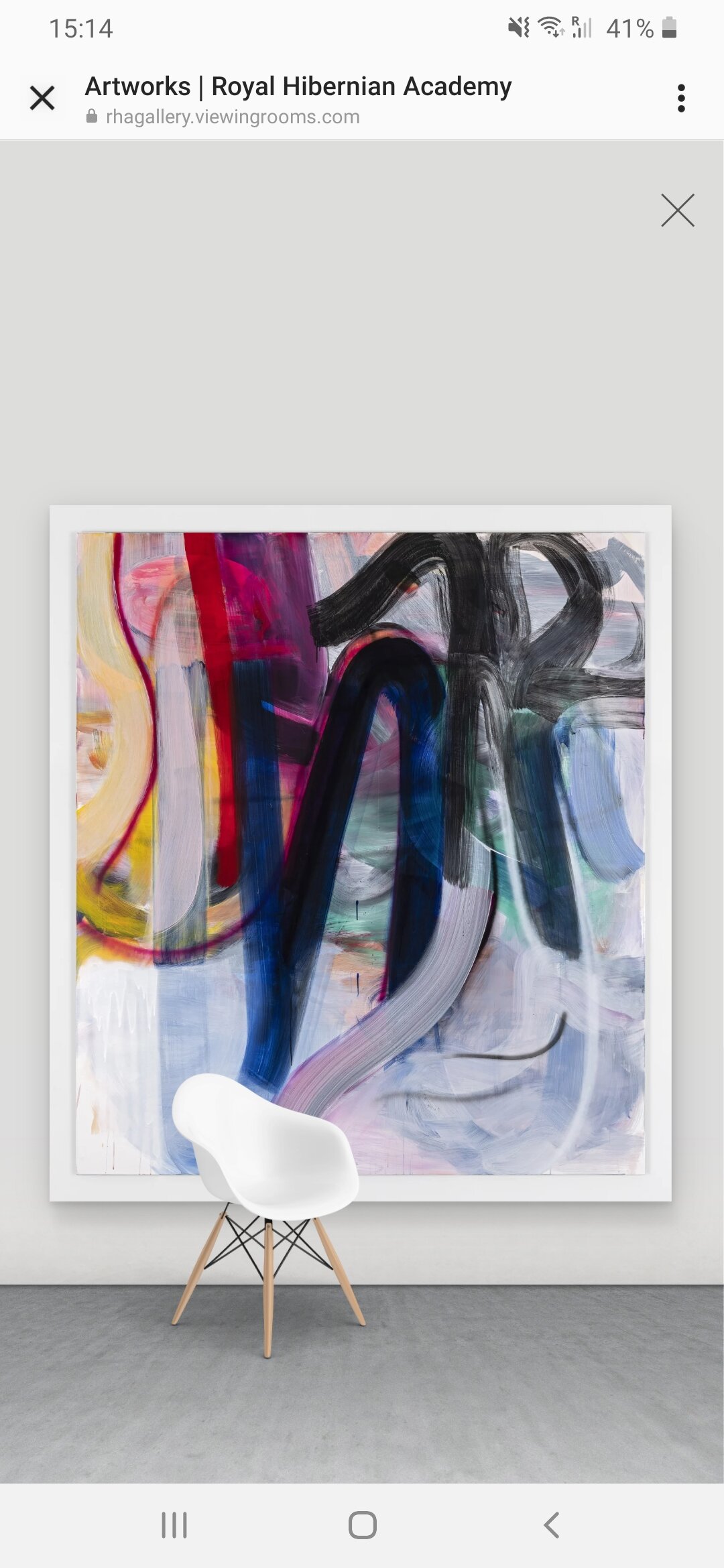

Against and within this setting, Flood’s paintings infer ruined civilisation from the vantage point of the lively wilderness of painted forms. But not just from an objective looking down from the concrete and conduit rafters of Green on Red, but ruination from one painting to the next. As I enter the gallery, paintings are full and fat with colour and paint, but gradually recede and disintegrate to end in a withering and anaemic painting at the far back wall, with bone-white broken sculptures of fruit and veg sprinkled on the floor beneath.

Green on Red’s crumbling — but never fully gone retail potential — helps with the culture-cum-civilisation simpatico between Flood’s work and the space. They know each other. Standing here I think of culture as always coming while simultaneously disappearing from view. I think of culture as not permanent; a flash in the pan. Its power not residing in the archive or the record. In this space, among these paintings and painted things, the idea of culture becomes one of momentum and transition. Green on Red, like culture, is set in the dusty concrete of its own decay. The gap-toothed walls held together by the braces of a hollow building waiting for commerce to save it, not culture to sustain it. Green on Red (with art) is more representative of culture than civilisation. Filled with Flood’s work it feels like I am standing in the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum with triple glazing. It is more 2010 artist-run than 2020 artist-run. The white and polish of commercial spaces and art museums was never my thing anyway, and less and less so these days. I have come to think of them as agencies of consumption and control.

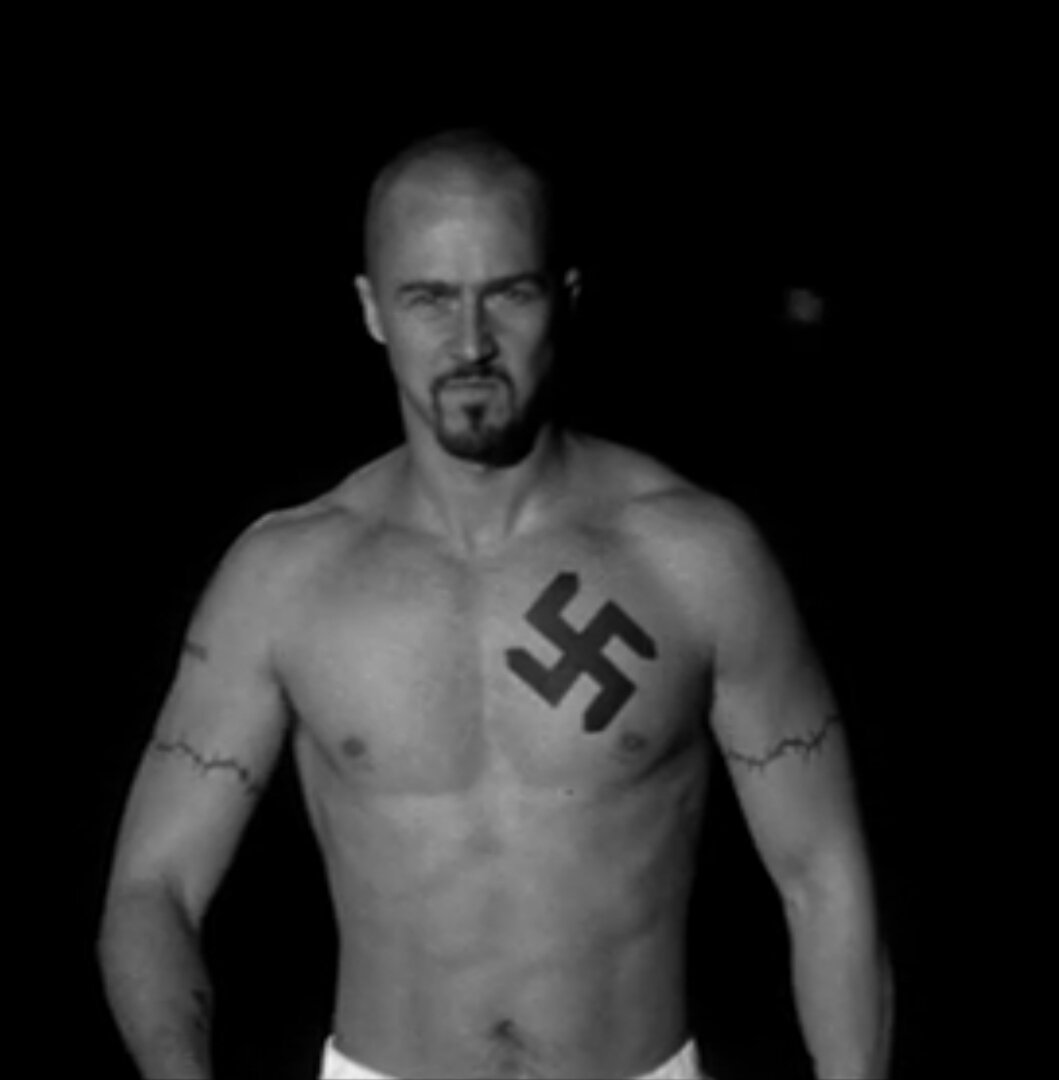

Flood’s project also makes me think about time, especially how, outside and inside the gallery, the low winter sun and cloudless blue expanse, frame and suffuse the work with light and colour. It makes me think of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity when it came to public attention, if not public understanding. When, up to its publication, philosophers were engaged in a metaphysics of space-time á la Henri Bergson et al. Why I think of Einstein and Bergson here is because the transition from a philosopher’s theory of time to a scientific theory of time is documented in Katherine Waugh and Fergus Daly’s film I see Darkness, screened concurrently down the road at the Museum of Photography Dublin. In a debate in New York in 1922, Einstein asserted that there was “no such thing as a philosopher’s time”, and that Bergson’s version of it was merely “psychological time”. In some ways I feel Flood’s paintings lean towards Bergson’s psychological time. There is something about the ‘last’ painting in the gallery that is suggestive of the last painting Flood painted in this body of work, or will ever paint. In the same way Stephen McKenna’s darkest painting Large Night Interior exhibited at the Kerlin Gallery is 2017 was literally his last painting, and looked it too.

Stephen McKenna, Large Night Interior, 2016, oil on canvas, 90x120cm

Flood’s paintings (to my mind) are leaden with metaphysical content within a phenomenology of paint. Anselm Kiefer keeps coming to mind. Flood however is a kid-Kiefer, truncating and saturating massive metaphysical landscapes into portraits of body parts connected by the fibrous (healing) tissue of paint. The artist’s scars, and manifest in different ways, different forms.

All this could be read as discontents, especially in person, contra the digital image of Instagram, which tends to colour and compress Flood’s paintings, resulting in graphically readable and digestible images, even desirable images, but sacrificing the minutiae of mess and the particular for the consumable, uniform, whole. Unlike online, I have never been able to digest Flood’s paintings in person. We have two on our walls at home, which are still left undigested after 4000 breakfasts in their company. My gag reflex is always on high alert around them. That’s why art on Instagram frustrates me so much. It’s consumable. Capitalist. Easy.

Detail.

Freud’s Civilisation and its Discontents comes with a bevy of symptoms, fetishes, anxieties, repressions and so on. Flood’s pictorial mythology is not so explicit in respect to either the signification or representation of such discontents, except for the ever-present brain-pan. But there is a new emphasis re the silhouette or tear in the fabric of his warped time-space gradients. In one instance the profile of a vase is substantiated by an impastoed setting without, and a gradient setting within. The vase is a void to be filled.

There is a Sisyphean effort in Flood’s paintings that demonstrates a repeated ambition to reach beyond their flat and fenced-in perimeters, like the startlingly weird fingers that flirt and fondle the gallery walls. A fetishistic excess. A social and masturbatory gesture. The artist, symbolically and imaginarily, among others, but realistically, alone. The gold and glazed ceramics of heads and fruits seem to exist out of exasperation, the last death rattle of culture echoing in the halls of civilisation. One last breath before everything turns to stone, to history, to dust.

Of course we can be more light-hearted in our estimation of Flood’s work. Less heavy. Less elevated. Less. His work is deterministic, tacit, in its painterly objective. Raw linen or gradients are the consistent foils for his spoiled paint. After inspecting Flood’s paintings all these years, I find they continue to use the same raw repertoires and transitional effects to balance the neurosis of the clotted and complex builds and weaves of monstrous forms. The other stuff in the gallery, pottery gone bad, is like the cutlery on a well-dressed dining table, where animals toast to civilisation, while stuffing their gout faces with the spillover and excess of capitalist culture.

So can we digest the paintings of Flood without getting sick ourselves? Are they too much? They are paintings that are determinism to be themselves. They are healthy in their sickness to be, and to be more. They are science-fictions of the past, regurgitations of what was to what could be. Skulls and mountains, death and the sublime, earth and the ethereal still pervade and parade in the work. The lost and found of civilisation finds its home as a cornucopia of forms on the slippery when wet horizon of time and space, belief and heavy metal. It seems that Flood does still believe in illusionistic space, but illusionistic space without all the trickery. Like the farther you stand back from a painting the realer it gets. No. Flood’s paintings look the same up close as they do from afar.

There is a theory, one sourced from Immanuel Kant and later expounded through psychoanalysis, that we experience reality through fantasy. I wonder if all cultural production is a way of getting closer to reality. That somehow, among these works saturated by the natural low-lying winter sun, and further lit by the uncanny fluorescence of the gallery lighting, that painting, at its best, brings us closer to reality when it is displayed in the lights of day and detritus of life.

Green on Red director, Jerome O Drisceoil, mentioned Edvard Munch today. My brain bristled with identification. Munch is all about death and sickness and repetition, but so what. Death and sickness is commonplace for all of us. What makes Munch interesting psychoanalytically, and by extension artistically, is what he did with death and sickness in his paintings, an example and description that might bring us closer to the florid obfuscation of Flood’s work.*

Damien Flood’s paintings are at odds with themselves — if we can use that pronoun. Landscape wanting to be portraits; lively still lives of nature morte identification. They are undead. Perhaps the nature of all contemporary painting is to become and not to become simultaneously. This is what Francis Bacon did so well, landscape as portrait, and the existential uncanniness of doubling the conventions of art history, whereby past becomes present becomes postmodern in a warped temporal and spatial relationship that would make Bergson proud. A narrowing of the secular landscape for something more sacred — can we say sacred anymore in relation to art? Einstein has left the building at Green on Red. The sun has dimmed. The blue turned to a pin-pricked black. And Bergson has reentered the atmosphere… in flames. We just don’t know if he will survive the impact. I think he will.—James Merrigan

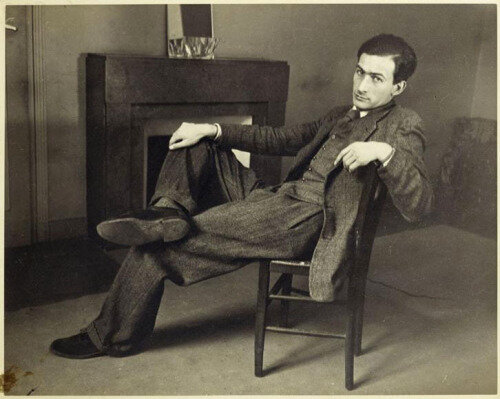

*Edvard Munch lost his mother at age 5; and his sister, who became his maternal substitute, aged 14 — she was just a year older that Edvard. Munch would experience countless other family tragedies throughout his 80 years, and would invest most of his energies in the repeated and periodically portrayals of his sister’s sickbed. Psychoanalysts have called Munch’s painted repetitions of his sister’s sickbed as a “lifelong transitional object” — reflective of the Freudian death-drive — an object that helps the infant transition from the mother’s incubated embrace into the real world. But I think what some psychoanalysts define as a transitional object is in essence a fetish, something that loses its healthy and developmental definition, to one that is more cultural in a corruptive and destructive sense. Recently I have been thinking a lot about Edvard Munch, and at the mention of Munch while at Green on Red, I started to understand Damien Flood’s work apropos Munch. More generally I wonder what motivated Munch to paint what he did and the way he did? There was the fin de siecle permissibility in terms of what a painter could paint at the end of the nineteenth century in respect of expressionism. There were the tragic formative years of his childhood, which we can psychoanalyse, and further label his paintings as life-long transitional objects or perverted fetishes. Leaving Munch behind, what if we ask the same questions of Flood? The fetish is many things, not one thing. It’s anthropological, it’s commodity borne, it’s sexual, it’s an object, it’s a psychic process. Outside of so-called normative sexuality, the fetish can be something more than a stiletto. The fetish can be a hamster. Slavoj Žižek tells a story about a friend of his who lost his wife. Žižek says they were very much in love, but for some reason his friend didn’t show any signs of sadness or mourning for his deceased wife. To the point that Žižek felt his friend was psychotic. Later Žižek discovered that his friend was keeping a hamster, and not only keeping a hamster, but on bended knee, caring and loving a hamster. When the hamster died, Žižek says that his friend was heartbroken in excess of the little creature he now mourned. Of course the hamster didn’t invoke the sadness that his wife’s death couldn’t — the mourning for his wife was just delayed, suspended in the object of the hamster. So the fetish is less an object of a specific aesthetic, and more a fantasy-process that can be fixed to any object, stiletto or hamster, when the world of meaning or emotion is pulled from under us. The fetish is defined by disavowal. That is why I believe that all artists are fetishists. Žižek calls the symptom a partial truth, and the fetish a partial lie. Edvard Munch whipped his paintings; he also placed eyelashes in his paintings. In another sense the fetish is a way of coming close to death without dying, close to sex without having sex, close to the absolute without succumbing to it; close to art without having to make it. As Georges Bataille said, “The fetishist never loved an old shoe more than an art lover loved a piece of art.”

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)