SEAN EDWARDS: FAULT OF STYLE

You have to squint your eyes to catch the conscience of Sean Edwards’ art at TBG&S Dublin. When you do, eyes dilate to a Local world that, through a series of micro-expressions, twist and turn the nature of looking and feeling.

It seems grim nostalgia was already creeping — almost too soon, too young — into Sean Edwards’ aesthetic attitude in his early 30s, when he made Dream of Him (2010), a small, personal photograph of childhood trophies inset centre-stage and square within a large photograph of the adult artist’s studio wall. The juxtaposition is weird: the small photograph reeks of a 1980’s sitting room replete with the itchy, damp and brown-yellow accoutrements of a 1980’s sitting room; whereas the large, white, anaesthetic backdrop of the studio wall looks almost lunar in topographic comparison, intimating great polar distances in space and time, adult and childhood, life and art. Like Duchamp, Sean Edwards appropriates the dinge and dirty of society, mixed with a conceptual architecture that, at first, comes across as arch or decorative, but up close, smells of stale alcohol and gambling BO. Perspective is the making and loss of this exhibition.

It’s the perspective shifts between small and big, close and far, single and double that stabs you in the back here. That is, If you stay for a while — most don’t. Most glance at the objects in their formal doubling and singular entendres, uncannily reproducing themselves to dizzying and decorative ends.

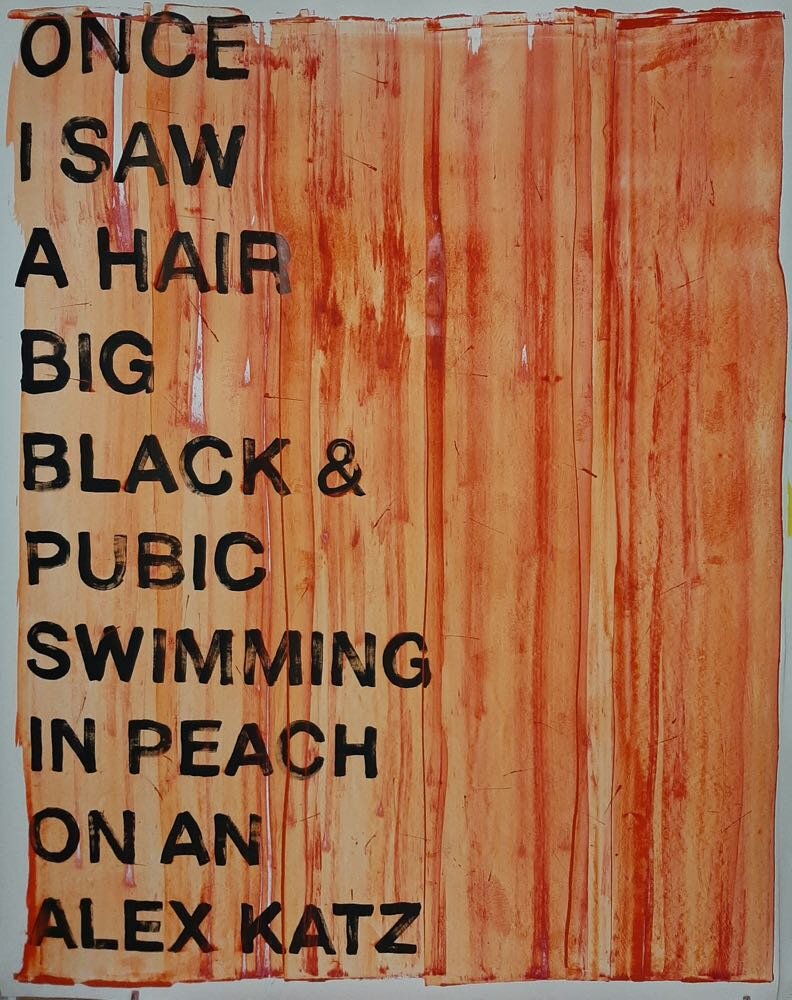

Sean Edwards' work is far from pure decorative. And yet his dioramatic constructions have enough pattern, repetition and symmetry to slow interpretation to a concentric rhythm. But reading between the veneer and the disturbed geometry, the artist has something to say beyond the decorative, whether that message is distilled through a stained sherry glass or the grafted imagery that sidewinds and fractures the formalist resolve of his art.

It’s like this: Sean Edwards sadistically slices and dices his memories of Wales, and then sadistically and masochistically puts them back together again like humpty couldn’t; and then sadistically and masochistically puts everything out there in plain sight for you to discover in incremental, insect-scale ways. Conceptual woodlice.

We also have big things here, like the Richard Deaconesque Stations, fabricated from veneered MDF that loop, contort and repeat bookmakers’ Logos (LADBROKES etc) on their ribs. The gallery attendant hands me an off-cut of the same logo-infested rib, like someone might in a flooring shop, in anticipation of me monkey-bar swinging on the 14 sections that range across one wall of the gallery. Sean Edwards’ objects provoke touch or rearrangement by hand or imagination. Others before me have been pawing his ribs hence the existence of the spare rib. I hold it in my hand; a cane to offset my stutter and stumble.

In my other hand is the gallery handout, which does a lot (too much) describing and explication, so to repeat here, like the rest of the cut-and-past promo reviews to follow, would be another tautological exercise. So let’s not do that. Tautology, in a manner of speaking, is the definition of nostalgia (to superfluously repeat or relive what has been said or done before). In that respect, Sean Edwards’ dioramas of times lost, loved, forgotten and remembered are tautologies. That said, as defined in mathematical logic, “a tautology is a formula or assertion that is true in every possible interpretation”.

Sean Edwards’ warped perspective is sourced from an isle close by, but an isle drifting farther and farther away as time goes by, as current geo-politics oscillate and escalate between cohesion and separation, tolerance and war. But this is smaller than all that big stuff. This is very much Local, very much micro in its expressions. So much so that a lot of squinting is needed in extrapolating the explicit but easily missed minutiae of Sean Edwards’ formal vis-a-vis conceptual contortions.

1980’s Wales, not unlike 1980’s Ireland I guess, is a time best forgotten, and certainly not relived through the sophisticated and purging display-case of the contemporary artworld, a world that forgets, fetishises and commodifies better than it remembers. Sean Edwards remembers for all of us, especially those who don’t want to remember. Like me.

Much later I think to myself that, by accidental context or ruthless unconscious, this is a post-Brexit exhibition: an exhibition coloured by past political separations and present emergent Kingdoms and Empires; an exhibition that evokes — amidst the gallery cleanliness and godliness — stale carpets and tobacco-tinged walls of working class homes and gambling houses; an exhibition that smells of memory, recession, emigration, mining strikes, not the distracting and hurtful perfumes of nostalgia, mourning or melancholia; an exhibition that bottles and battles stagnant time, standing still for the artist, but broad enough in the re-representation of forgotten and found paraphernalia to elicit a time in us that we, or our parents, experienced, but a time, thank god, that has now past. A time so stilted, damp and dark that it is best left repressed and denied as a joke or a stain, not a trophy.

12 years on from Dream of Him (2010), Sean Edwards is forty-something now. As a forty-something artist, and parent as the press-release and double text work makes clear, the past begins to weigh heavier than the future. This can amount to a formal contortion as the past becomes a source of form and content, and perhaps comfort for the artist. Especially considering how artists generally contort themselves into a möbius strip of tautological form and content. That said, “tautology” is sometimes defined as a “fault of style” (e.g. they arrived one after the other in succession). Contra-style, which superficially defines art in theory and market, “Fault of style” could be the very essence of art. —James Merrigan

Through 12 November 2022

TEXTS

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)