DEAR SKATEBOARD

Congratulations!

You debuted at the Tokyo Olympics this week. Mainstream newspapers — The New York Times, Guardian, Independent — have embraced you out of novelty rather than passion. The coverage is shallow and repetitive, journalists depending on the second-hand words of their peers for their copy, not real experience. “Sellout” headlines follow you amidst this Olympic “achievement”. The writers depend on Nyjah Huston alone to poster boy their ignorance. You are more than Nyjah or Tony Hawk, more than gold, silver or bronze, more than airbuds, shoe deals or skate games, more than the billion-dollar industry that you have become, more than an official sport sponsored by Nike that's been nationalised, uniformed, institutionalised, named. I still hesitate to call you a sport as you were so much more to me than a sport when I adopted you from age 12 to 23. You were a lifestyle, a culture, a rebellion, an attitude, a style, resistance, art.

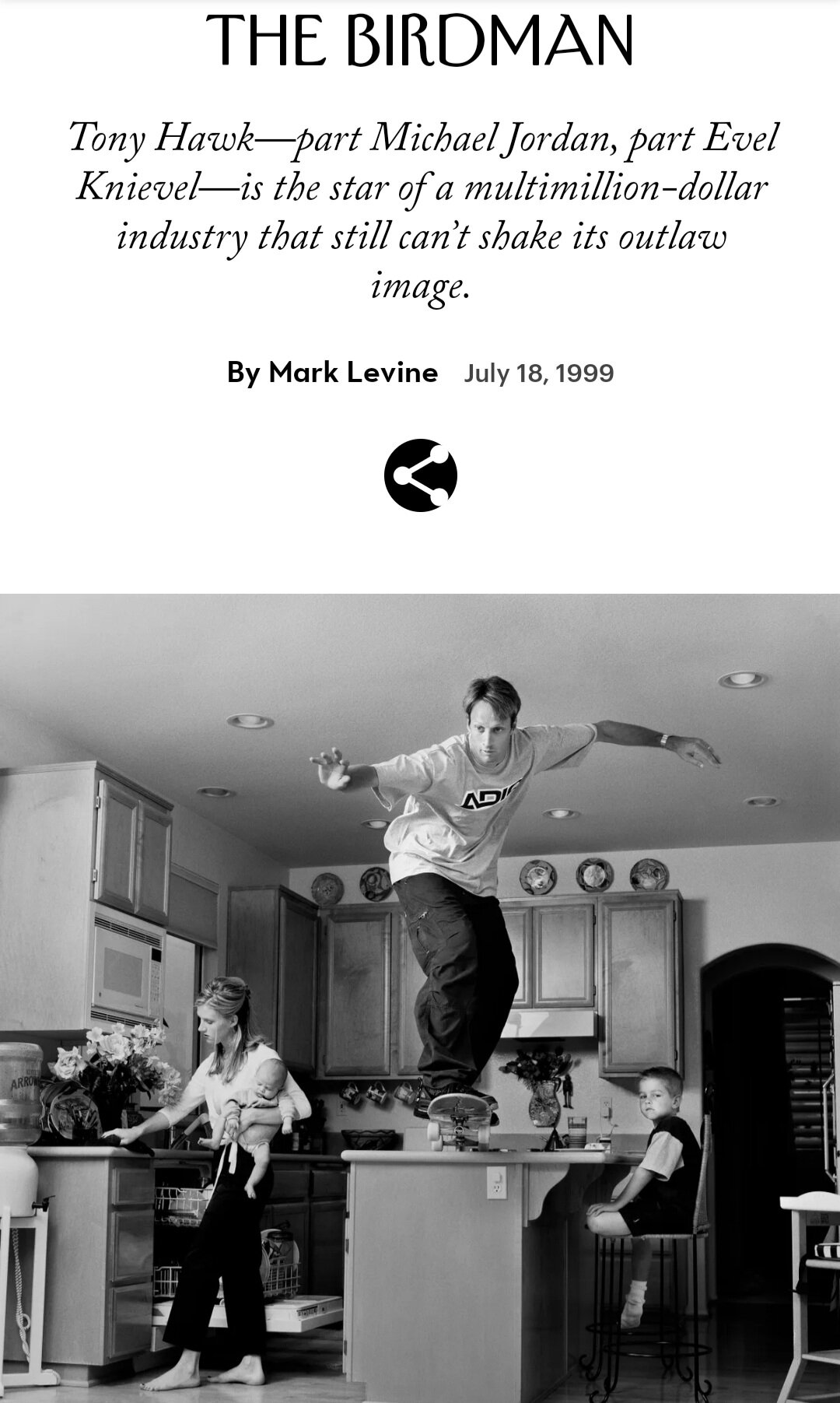

New Yorker Magazine, 1999. (READ SUBHEADING!)

We first started skating you down steep hills in a rural Wicklow, Ireland; power sliding and pivoting, creating an explosion of noise that was socially abnormal and individually awakening in a cow-caked universe that never changed its clothes or its smell. We shredded on you down those hills all day, leaving bits of ourselves (and you) on the hot tarmac and spattered gravel. The feeling on those hills was fun, free and full. You owed us nothing; we owed you everything. As the late editor of Thrasher Magazine Jake Phelps put it: “Skateboarding doesn't owe you anything but wheelbite in the rain.”

Thrasher Magazine (1st Issue) January 1981

Fed up of wheelbiting in the rain we imagined there was more to you than a horizontal deck — grip tape up top, trucks and wheels down below. Problem was there was a famine of influence where and when we found each other. This was potato Ireland, before the Internet and the grey bureocracy of skateparks. We had silly glimpses of the possibilities of you in 1980s films like Police Academy or Gleaming the Cube. We broke the ReWind button on the VHS player to piece together something that we could use to lift you into the air. In those Video Days we surgically discovered how to Ollie then flip via watching videos via watching each other. We continued with severe drive, individualism and independence to keep you underfoot. My 6.6 ft. frame broke you so many times that I couldn't afford you anymore at €50+ a pop. But when I did I popped you big, flicked you big, grinded, pressured and wrapped you big: kick, heel, tre, pressure, impossible, cab, nollie, fakie, switch to the slap of a horde of you.

Jamie Thomas & Donny Barley. 1990s; photo: Ed Templeton

The people and police were against you from the start. They didn't see the thing that we saw in you. I cannot describe that thing we felt riding you. Perhaps it was the push and pull of the world underfoot while the external world eyed you up so disapprovingly. We were young and disobedient, wanting attention for the wrong things. When I look at you today I see you elicit an unapologetic elegance and grace in the awkward and rebellious teenager. You make embarrassed and sulky youth dance and smile. It's a weird meeting, you and the angst-ridden. But you saved us from patterned shorts and socks. You split the world into two: those that walk the main thoroughfare and those that skate the road seldom taken. You gave us a choice.

Bottom line you upset the status quo; the A-Z flow of unfreedom. You came with a stereotype which our adolescence then lived up to: drink, drugs, self and public annihilation. But we held and rode you with pride in our indifferent difference. When we got our hands on Thrasher Magazine and VHS videos Hokus Pokus, Useless Wooden Toys, Welcome to Hell — you made sense: you and life were inseparable. We had permission to be no matter what they said. We had a community that cliqued. The early zines and videos in which you starred portrayed the personality and style of the skaters, but also the personality and style of the culture that popped you. Under the arms and feet of these skate video icons you became a lifestyle that was all and nothing, nothing and all.

Nyjah Houston’s Instagram post after the disappointment of placing 7th in the Street final.

You got me arrested many times, even strip-searched when I was 18. During those times you taught me that difference was not tolerated by the main thoroughfare. You formed my identity in those moments when the world pushed back. The music we listened to got louder, the fashion we wore baggier, the style and the tricks we made our own more in touch with what we needed to express. You never made us anti-social, you made us exhibitionist. It was your presence on the thoroughfares of normalcy that made others anti-social in their reaction and resistance to a way of life we had chosen for ourselves.

Tyshawn Jones, fakie ollie with a fontside drift; photo: Mehring

23 is the year Ernst Gombrich tells us the artist comes of age. I gave you up to be an artist at 23, but your culture, especially the one I bonded with as a teenager, has influenced me to this day in my art, writing, and institutional critique borne on a subcultural attitude to break in order to create. After wearing the slogan “Skateboarding is not a crime” for so, so long, you are now an Olympic sport. It's funny, as a teenager I met and asked skater Jason Lee for an autograph in a skate shop on Haight Street, San Francisco. When I recognised him in Hollywood films much later – post the box-office failure of Mallrats – I thought he had sold out. There is something about the transition from subculture to the mainstream that grates on the nerves of skateboarders dedicated to retaining the image and identity that attracted them to skateboarding in the first place as kids. The rub rubs deep and long. I rolled on you that second time because of the first feeling; I skated you for over a decade because of everything that you pushed and pulled me against. You were always against; a dissenter rather than cementer of opinion.

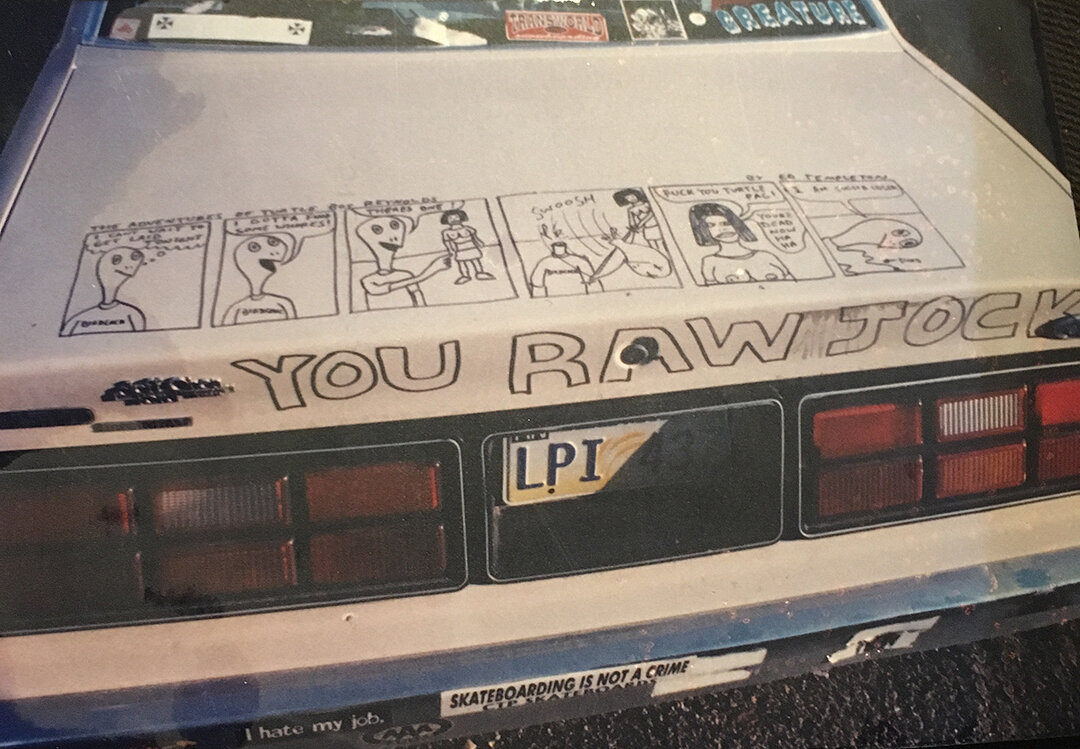

Ed Templeton's demo car artwork; photo: Donny Barley

You might be interested to know that a new breed of skateboarder will be riding you at the Olympic Games, one who is the antithesis of Nyjah Houston's competitiveness, and who is conflicted about his participation, summed up in a quote that vies the creative spirit of skateboarding against the competitive spirit of the Olympics: “Am I there to help skateboarding, to help spread creativity throughout the sport, or am I there to place the best and try to beat everybody?” His name is Andy Anderson, who solely represents his native Canada, and — as his Instagram handle evinces @autheticandyanderson — the authentic spirit of skateboarding. He will ‘P’ you all over the Park — plant, pivot, primo and pop — at the Tokyo Olympics. And going by his Olympic qualifying run at Detour, which blended freestyle with early and contemporary street and vert, the judges will be hard pressed to judge his “Malto manual shit” against what his peers are doing today. Andy Anderson is a wholesome and nostalgic redescription of what skateboarding was — an anti-social and destructive urban menace — and what it has become, a billion-dollar industry and competitive Olympic sport. Problem is, if Andy Anderson's ideology is collective rather than individual in spirit, he will have to compete at the Olympics as only the finals will be televised to the world.

Olympic Gold skater, Yuto Horigome, filmed by skate icon, Eric Koston, switch tail-sliding an 18-stair rail in his part, The Yuto Show, 2021

You are now on the world stage. Mainstream newspapers keep on waving the white flag for you by suggesting you have finally soldout to the mainstream (This is also a sentiment shared by a percentage of the hardcore skateboard community). “Sellout” reads as a triumphant tagline – the editor's wet dream of misunderstood misfit come good. As an Olympic sport more money, films and fashion will be made in your name that will outfit you in nostalgia, what Jean-Paul Sartre diagnosed as a “retrospective illusion”. The money-making percentages will breed inequality. But you will still aggravate the world: it's curbs, rails, walls and security guards. Like the artworld, we can choose what terrain, what grain to slap and pop you against. Subcultures never grow up, no matter what resistance or acceptance is put in its way.

To write, skate, make art — all the above and above all — is to resist.

Good luck Andy Anderson!

—James Merrigan