THE PERFORMATIVE ATTITUDE

Believe me, when a critic calls out another critic on something they have written, there is always something behind it. Call it posturing, or a fear of irrelevance, there's something behind it. It took a few days to decide whether or not to post this text. I wondered what was the value of such a response, what did it matter. Was I performing the same thing I was being critical of? Would it be better just to shrug off the above tweet as social media performance (something we are all guilty of), or invest some time in the emotion that made the artist share the tweet with me in the first place. I think I would have shrugged it off if I had come across it directly on Twitter, not second hand by text message. “Twitter is not writing, it’s signalling.” (Margaret Astwood). And yet this tweet's whispered momentum made it more attractive. What was it about this shruggless tweet that kept parroting on my shoulder? To be honest it was the critical attitude performed in the two sentences conjoined by the personal and the public, the confessional and the performative, all entangled in the artist, institution and journalist that interested me. It was also the timing. After years of writing art criticism, I have only recently begun to question the performative in writing on art, whether an excess in irony, sincerity, modesty, posturing, or the literary, all masks that afford the writer evasiveness rather than commitment. Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, it is the artist's shugging silence that meets a social media post like this that rubs me the wrong way. I know I have publicaly silenced artists from time to time through my art criticism, negative or positive or performed, but I have always tried (and failed) my very best to unpack my later criticism in long form. Even though art criticism is dead, I still find myself invested in its zombie purpose. To write is to resist.

A few things need to be disclosed before I continue: I am a friend of the artist named in the above tweet, and I participated as an interviewer and writer for the exhibition in question; I have not corresponded with Damien Flood at the time of writing this response as I did not want to create any more conflicts of interest or biases that already exist. Knowing all this I would like you, the reader (artist or other), to do a thought-experiment: while reading the above tweet, substitute Damien Flood's name with your own name, and see how it rubs.

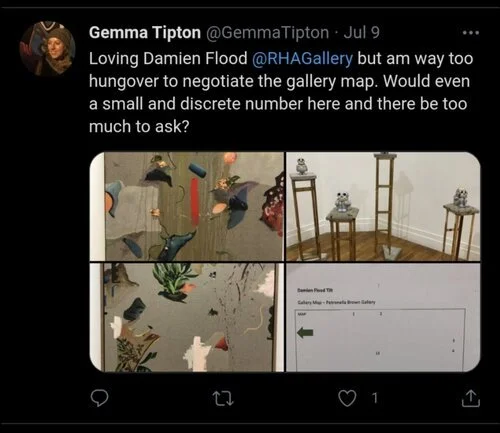

At first glance the above tweet posted at 12.40pm on July 9th 2021 by art journalist Gemma Tipton, and forwarded to me by an artist but not the artist directly addressed in the tweet, may not warrant such close analysis, being a tweet written when “hungover”. But here I am digging into a banality that seems to give a more profound picture of the social media world we perform in, than something supposedly more profound in its ambitions and the subject that provoked this tweet, art.

It is the compliment “Loving” used to soften the original intent of the critical expression to follow that can be used as an opportunity to helter skelter the sobriety of Irish newspaper art criticism, something that Irish artists have forever been disenchanted with but tolerate for promotion sake, into one that might be more drunk, interesting, and absurd in its knee-jerk manifestations online. What's the harm in criticising a gallery map anyway?

Well, context decides. We first have to take into account the context of a newspaper journalist with over 3,000 followers writing for one of the few mainstream newspapers that cover visual art in this country. Should a person of rare journalistic influence in the arts critique the administration of the gallery setting in a hungover state, a state that precludes one to experience the exhibition the way it was set up to be experienced in the first place, and then tweet it? Is the map the problem, or is the hangover the problem? Is the relationship between hangover and map not mutually inclusive?

Let's take the first line “Loving Damien Flood @RHAGallery but am way too hungover to negotiate the gallery map.” “Loving” of course is social media argo, like the ubiquitous “amazing” and “great” on Instagram. It's a way of saying something positive without doing the work. It is the public proclamation of your presence in the here and now of the gallery, on your own time, experiencing the free work of art, and the artist and institution in question should be privy to that fact, along with any default followers. In essence, tweets posted while in the art gallery are more about the person posting them than the event they are momentarily hosting on their social media feeds. This is the point of such expressions, whether hungover or not. “Loving, amazing, great” are not, I repeat not, value judgments. They are expressions that barely exist before floating into the air like the child's birthday balloon. The crying comes much later, and in private.

“Loving” followed by “but” can be translated as, “I was loving this but…” It's a case of stringing Cupid's bow but twanging the arrow's release and missing the heart. And there's lots missing here in this tweet (not just gallery wall numbers). Further, the misses are performative misses; for instance the missing 'I' in “but am way too hungover”. This is of course another symptom of social media expression, to feign casualness through grammatical suicide. We do this all the time to inscribe tone or attitude in our free and loose social-media commentary, which goes by a set of rules harsher and more institutionalised than the ones policed by the outside world. Just because we are in control of the rules of our expressions doesn’t mean they are not institutionalised, whether by Facebook or other people posting and policing your feed. This tweet, critically banal but fascinatingly absurd as it may be, brings to the surface the existence of the private consciousness we all bear but somehow believe we subsume beneath our tonal acrobatics via word use, emoji choice and abbreviation on social media towards some attitude that is conditioned by the external world that we think we are resisting.

The second line of the tweet — “Would even a small and discrete number here and there be too much to ask?” — is not a question but a criticism and rhetorical demand: of course the exhibition at this stage of its run will not be changed based on an individual's tweet no matter who they are. It's the “too much to ask” that is performative. The only question is: to whom is the tweet being addressed, the artist or the institution, as usually both have a hand in the administration of the gallery setting? The tweet's openness is the issue here. (Damien Flood is not tagged in the tweet, the RHA Gallery is, but the artist will surely find out about it, either as to alert him of its absurdity or its promotional value, the same way I was alerted to its existence second hand by way of a text message.)

A criticism of a gallery map (which indeed looks like a pinball machine) is the most banal criticism. However banality should not be confused with harmlessness. The question that such a banality proffers – written as it was in a “hungover state” – is: was the hangover the cause of Gemma Tipton’s inability to navigate the map? Most likely. Was the absence of gallery wall numbers the cause of Gemma Tipton’s confusion? Perhaps. Or was the tweet, written in the cabbage sweat of a hangover, just a silly amalgamation and manifestation of all those things: hangover, map, performative tweet? I use "silly" performatively to make my next point.

I understand provocation as someone who has practised it many times as an freelance art critic for over a decade. In my youthful criticism I used provocation to elicit a response from what I felt was a silenced arts body politic. As someone who was an exhibiting artist, shy in temperament and evasive of conflict in the real world, I performed my provocations absolutely, which is one of the reasons I worked under the moniker Billion Journal for so long, as I could shore the responses to my criticism on a psychologically separate island. But I grew up, and decided to really think through my tendency and desire to critique – criticism being something I think is more necessary today than ever – to bridge the gap between a probing journalistic temperament and one that is more critically nuanced and reflective on the personal source of that naturally dissenting attitude.

Social media is a performative space where we create attitudes not real people. The harmful thing about this is we begin to believe in our social media attitude because of the validation it gets, validation we do not get in real life. Social media is a personal poison but also a spiralling venomous snake held by the tip of the tail. I learnt in recent years that art criticism is about working through rather than over the personal source of your criticisms of the world in private before sharing those criticisms with the world in essay form. Nothing less will do. You are implicated in your criticisms – that's the personal risk. The performative brevity of social media is not the place for commited art criticism, because it is entangled in the performative attitude of the individual.

—James Merrigan