On Mourning Mark Fisher Mourning Culture

“Strumming my pain with his fingers

Singing my life with his words

Killing me softly with his song

Killing me softly with his song

Telling my whole life with his words

Killing me softly with his song ”

“Much of listening to dance music consists of trying to recover a feeling.”

“…mourning is always already political…”

“They say, the problem with nostalgia is, that it makes us overrate the past. But I think the problem we have is overrating the present, and underrating our own dissatisfaction with the present.”

“I don’t want meaning… I just want things to work better.”

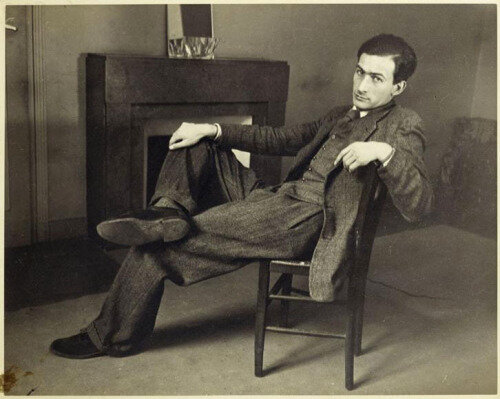

Cultural critic Mark Fisher’s self-reflexive question in a seminar over a decade ago, seems a pathological question to ask today. “Can one make negative judgments about the present moment? Or is any critical judgement being exercised about culture somehow inherently oppressive?” Mark answered with the following: “Certainly one can make negative judgments about the present moment. And to pursue this dialectic loop to its full extent, the reason why culture is bad is because there is not enough negativity.”

For the past few months I have been rereading and listening to Mark’s particular brand of awkward, intense and open criticism of culture, voiced under what he perceived and felt was the overwhelming pressure of capitalist realism, and his mourning — not nostalgia — for what was.

Looking back on the capitalist realism of Mark Fisher (aka k-punk) there is a real sense of disenchantment, melancholy and mourning for what was, what is, and what will be… or never be. His writings and lectures show a deep and concentrated effort to confront the impossible present with an equal measure of criticism and emotion, but cognitive and weary of nostalgia to substitute or obfuscate action in the present. He described his writing project in toto as: “Revealing the inherent negativity of the moment in which we live.” What a slogan for our times! With little to valorise in respect of cultural resistance or criticism in the times we live in, Mark’s impassioned and heartfelt plea for an alternative seems even more relevant today, five years on from his death by suicide.

Before I continue, it is important to clarify the difference between nostalgia, that psychological phenomenon of the good past that arrests our attention in the terrible present, when we can’t face the contingencies and uncertainties of the present; and mourning, which like melancholy, is something we feel and carry (over time) at a deeper and heavier level than nostalgia. Mourning is both individual, collective and “political” in Judith Butler’s terminology. Mark could be accused of nostalgia for the UK punk and post-punk periods, when cultural resistance was part of the dress code, lyricism and rhetoric. So we must be careful here in respect of nostalgia and mourning, and to not conflate the two. Nostalgia stems from negativity, but always negates negativity, whereas mourning embraces negativity. Nostalgia is fetishistic disavowal at its most pernicious, where fantasy and defence dance around the negativity of the present without confronting it head on. Mark confronted negativity head on. He is a mourner.

As a cultural critic and naturally consistent mourner, I have empathy for Mark’s project to reveal “the inherent negativity of the moment in which we live”. Truth be told, I am looking back at the art scene with less social mobility and energy for the other in terms of art criticism as a father of two young children. You give a lot of yourself as an art critic. It’s not a sociable condition. Especially when you approach and broach negativity. But as Mark says: “The motor of culture is negativity and dissatisfaction.”

You can find countless definitions of Mark’s capitalist realism online, such as this suitably fatalist one: “Fisher proposes that within a capitalist framework there is no space to conceive of alternative forms of social structures, adding that younger generations are not even concerned with recognising alternatives.” And yet, countless times in lecture theatres around the world, Mark repeatedly admitted that a definition of his notion of capitalist realism is always out of reach or date, adding that the word capitalism is not a word that the general population use to define their place in the world. In a sense, Mark’s difficulty in defining capitalist realism is the definition of capitalist realism itself, as something so deterministic, tacit and naturalised in society, that it consumes and conjures itself while we consume and conjure capital through it. Capitalism is self-perpetuating. Capitalism is the parallax gap in subjective judgement.

Mark supplemented his vanguard assault on the wall of the present with music. Music set the mood and tone for his lyrical klaxon call for change or, at the very least, a post-capitalist alternative, whatever that could be... Music was his way into a distracted, disenchanted and disenfranchised generation (him included). Music equates to mourning in Mark’s awkward lyricism. Sometimes he introduced a lecture, not with an academic quote, but with songs from the electronic, dub-step, garage, drum and bass, or ambient genres. “Much of listening to dance music consists of trying to recover a feeling.” There was something impassioned about his approach and plea. One heartfully and artfully attached to the idea of change or release from the techno-capitalist time he found himself unhappily thrown into, but still eager to have a dialectic relationship with, even though, on the retrospective face of it, it hurt. He wrote towards an alternative to the growing cultural malaise, but always with Fredric Jameson's remark whispering bracingly in his ear: “It’s easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.” Mark Fisher hung himself in 2017. He was 48.

Mark comes to mind now because I find myself listening to a growing playlist of disenchanted songs that he used as a sonic backdrop to his writings, from Burial to The Caretaker. I think it’s an age thing, and something Mark (and every cultural critic worth their salt) comes up against time and again, in his critical articulations of the present as an ageing theorist, from a transitional generation – vinyl to digital – in the accelerated time of the internet. Once again, he found himself in the gap between what was and what is. He wasn’t able to surmount the contingent uncertainties of the present, no matter how he tried. And he tried. He really did.

Mark was caught in what one of his favourite philosophers to cite, Slavoj Žižek, calls the “Parallax Gap”, a temporal and spatial gap between what Kant referred to as the phenomenal world (how we perceive the world through time, space and causality) and the noumenal world (the world separate and not dependent on the human to perceive it). It is in this gap where philosophy disembowels itself; a subjective space where the internal world vis-a-vis the external world is obscured by the very subjectivity of the one trying to see. We are in our own way most of the time. We are all internally blind to the external present, and great insight is always blinding. And when you throw history and emotionally charged attachments into this philosophical architecture, as Mark did, the eyes in your head become two pinpricks in an infinite universe amidst a dilating night sky.

My growing playlist of Mark Fisher and electronica comes at a time of personal disenchantment and distance from the local art scene. This disenchantment has many sources and perspectives: not living in the city; co-curating an artist-run space on the periphery with a dwindling audience; looking at the art scene through the lens of social media. From these warped perspectives and distance, the art scene looks like it’s receding into a virtual homogeneity, that is always moving towards something, producing something, being part of something, winning something, looking forward to something… something… something… some thing. Perhaps online is Kant’s noumenal world made manifest.

The only moment in recent times we had a reprieve from this forward-moving virtual onslaught toward something — always good — was during the pandemic, when artists retreated into nostalgia on Instagram, which, in a manner of speaking, was just another mode of phantasmic production. You have to wonder what all this production and waste is for, or goes toward. Indeed, artists are the best producers. Content, in their hands, becomes a sublimation of living. Marcel Proust’s 4000+ pages epic In Search of Lost Time is an ironic testament to that fact and fate. The artist’s life is a life of looking intensely at life while fearing living it. Memory and mourning is all that remains for the living.

Living has always been the capitalist crux for the artist. We live in a society that feeds off culture but is unwilling to feed artists. Instagram’s positive-production does not tell the story of artists barely able to sustain a life in an untenable economic urban environment in terms of living and studio spaces in the city. Artists are leaving the city. There is a cultural loss in their exodus. Artists are always better, artistically and psychologically, together, as in art school. Mark Fisher described this positively as the cultural concentration of the city. That said, the artist’s lifeworld has always been conditioned and shaped by society and capital, by the shifting housing market in the city. Mark mourned the collective no-wave moment, which effloresced in the empty capitalist husk of New York in the late 1970s. I myself return to 2011, during the financial crisis, when the original Basic Space Dublin made collective and solo excavations in the city with enigmatic and dialectic ambition. Perhaps we all have moments that define culture at its peak and trough.

Underground, 20/11/2011, Basic Space, Vicar Street, Dublin 8

The recent exodus of artists from the city and real life has led to a trenchant individualism, as artists become dispersed in the countryside, to only find a phantasmic community and solace on social media. In this respect, the property market is the determining factor of the fate of culture, the artist and possible resistance or alternatives in the city. Mark was speaking about the cultural ramifications of high rents and new laws against squatters in the UK long before the rise and fall of the economy; and how the idea of “public has become pathologised” (like criticism) before the exodus of artists from the real world to Instagram. Although Mark did warn “it will only get worse” in terms of our physiological and psychological dependency on social media, I don’t think he could forecast how bad it would become in the preceding years after his death.

I emerged from art school as both an artist and art critic during the global financial crisis in 2008. Even though public funding for the arts was obliterated, art centres temporarily closed, and our long-standing visual art magazine Circa was no more at the very moment I started writing for it, there was an efflorescence of damp and wall-crumbling artist-run spaces. DIY culture replaced capitalist realism for a moment. Artists made exhibitions in their city bedsits; artists became collective and unnamed in exhibitions. The momentary glitch in capitalism in 2008 forced artists into urban cubby holes that had no in-house graphic designer or aspirations for vinyl on crystal-clear gallery windows. Framing was not a thing like it is today. Things were desperate, even depressing, but they were exciting too. Raw. And this is not nostalgia, it is mourning. I wrote about my excitement and the possibilities at the time of Basic Space, without the fantasy or defence of nostalgia. The present became a future possibility for an alternative.

Today, especially through the lens of social media, there is a constant, libidinous, low-level negativity that never reaches a peak of outburst under a suspicious self-satisfaction. Negativity is not allowed on Instagram for fear of disturbing the status quo of passive closed smiles hiding rictus rage and envy underneath. Well, that’s what I imagine instead of the perhaps more likely settled inter-passivity. Artists exist on a feeding tube of virtual highs and lows that prevent any change or alternative from taking place in the real world. The world is flat.

The momentary exodus from Instagram to VERO last month was a case in point. It showed a real want for an alternative in terms of social media platform. But in a sense, such a migration, same for same, is replacing one goofing off for another goofing off. We cannot imagine an alternative to social media in the real world because it doesn’t exist. Real life is hard work, awkward and embarrassing. Sometimes you can’t remember the name of somebody you meet, or the word for something IRL. Real life is pathological in comparison to the fluency of online, where everything is known, not guessed or imagined. The so-called democratisation of culture has led to a levelling, where resistance (what Mark called in his punkish terminology “war”) is not on the protest cards. We are unwilling to risk our individualism or identity politics for the fantasy of we.

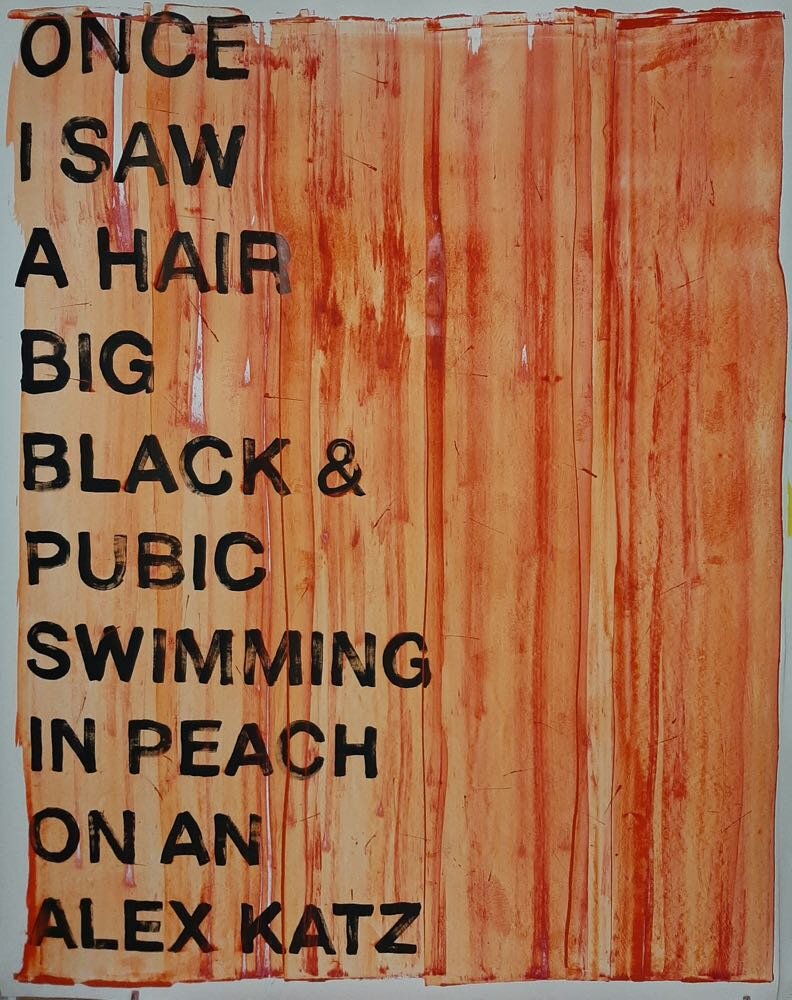

The state of play in our own city sees a new-wave of commercial gallery gambits, with painting (as always) as their pawn. Atelier Now’s mission statement opens with a line that is both a criticism and commandeering of the idea of the “art world”: “The Exhibition Programme at Atelier Now throws open the doors of the art world”, obviously inferring the art world is a closed shop elsewhere. The words “welcome” and “accessible” is the new branding argo for commercial galleries like Atelier Now and Hang Tough Contemporary, where ‘sleek’, ‘vibrant’ and vinyl-clad windows is the aesthetic. Dublin’s locally established galleries seem sacrosanct in comparison to this new sleek and vibrant vision, where clean and big gallery windows look out onto the streets, rather than turning their backs on plebeian pathways.

Atelier Now and Hang Tough Contemporary would have been viewed years ago by ambitious art school graduates (like me) as a particular type of gallery that represented artists, primarily painters, never mentioned in art school, but who sold paintings. However something has changed, what Mark cited as the “threshold of relevance” has been reached. Hang Tough Contemporary is now on the tip of young art-student tongues, whereas the critically and commercially reputable four or five galleries in the city are viewed unattainable, detached and elitist. Today artists are open (with the usual trepidation) to exhibit in such low-concept galleries, where a premium is placed on the quantity of framed artworks on walls over some high-minded conceptual conceit, that creates anxiety in the mind of the visitor rather than “well being”. Now galleries like Hillsboro Fine Art look high-concept in comparison. The claim that Instagram has democratised the art scene has bled into the physical art scene, where a hybrid blend of conceptually canny artists and others can be seen displayed together in formal inclusivity with no dialectic at play.

Voicing such criticism these days feels like conservatism. “Can you make negative judgments about the present moment?” I am not denying the existence of artist and curator-conceived moments of formal and conceptual invention and risk taking place in the city and beyond, through publicly funded Bursary or Project Awards, that are not concerned with oak frames, or art objects for that matter. But there was never a time, on my watch anyway, that a commercial gallery like Hang Tough Contemporary got this much attention by high-concept artists, or reached this “threshold of relevance”. Perhaps there is nothing to lose and everything to gain? Except enigma.

What was not fully resolved, and perhaps more enigmatic for that very reason, was Berlin Opticians, which lapsed its hybrid activities as an online and offline gallery with a stable of 10 artists in 2021. Not since Basic Space, a decade earlier, had a visual art entity activated a truly dialectic moment, one that independently changed how art could navigate and negotiate the dialectic world of art, from online to offline, concept via market. It was perfectly weird and contradictory.

I think in these contingent and uncertain times of art making and its dissemination online, artists that question their art's existence in terms of criticality, antagonism and resistance (and not to forget erotics, what both Mark and Susan Sontag claimed was missing from art both in formal and descriptive terms respectively), is art at its best and most necessary. Berlin Opticians was an entity that did just that, as it reflected the present moment, when art has become as much an online experience as an offline one.

Berlin Opticians was less punk than those critically self-reflexive and complicit New York iterations (Andrea Fraser’s for-profit Orchard Projects or John Kelsey’s Reena Spaulings), which were and are art spaces of ironical resistance to and compliance with the artworld market, that recycle market critique for its own promotional and monetary needs. Berlin Opticians was a brave move, and it took a curator to make the move: Marysia Wieckiewicz-Carroll. In 2018 it opened to a wave of crowded and curious anticipation. Curiouser and curiouser, it closed its doors online and off in 2021, while the streets were pandemic empty.

Today, the commodification of art seems more commonplace. Artists are always busy — a word I hate coming from the mouth of an artist. Busyness/business smacks of everything that Mark Fisher thought was wrong with culture. The perception that art school is for slackers should not be a snide remark borne on envious transference, but the truth. The romanticism that surrounds 1990s slacker-artist exemplar Laurie Parsons, is based on the fantasy that an artist can say “I prefer not to,” rather than continually proving their worth and value in the face of their parents or society through high production. What does it mean anyway when artists say they are busy? For what? For whom?

The artist’s need to fit in while being out of joint with society is the paradox of the artist’s lifeworld. But that’s what makes the artist special: the dialectic that takes place in their work and their place in the world. Within the figure of the artist, an inherent resistance and criticism exists in their work and their lifeworld. The artist embodies an alternative, they don’t need to profess an alternative; they are resistance embodied.

Mark Fisher undoubtedly staked a critical claim in his neoliberalism and social media bashing. Even though he made a self-reflexive effort to be dialectic, like Žižek, who “would prefer not to” take sides in the self-perpetuating paradoxical gaps of his own making, Mark took a side, sometimes to the point of one-sidedness. But he truly felt and believed theory could tremble the foundations of society so culture could emerge again in its antagonistic form. That is what set him apart: his intimate relationship with the words that trembled from his mouth and onto the page when the tempo of his criticisms sped-up to catch the conscience of culture. That said, Mark was fighting a losing race or war against the present, where and when the tracks of capitalist realism were already laid down well into the future, lying silently in wait, undisturbed by the vibrations of Mark’s voice from the past.

What makes culture culture, and civilisation civilisation, is culture doesn’t survive its momentary explosions and efflorescence in civilisation. Today’s cultural worker’s obsession with archives, history, conservation and legacy is on the side of civilisation. Mark Fisher was on the side of culture. And culture, at its best, is something that evades appreciation in the present, but haunts as mourning in the future present.

Thank you Mark for making culture tremble.

James Merrigan.

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)