Daddy Dancer Redux

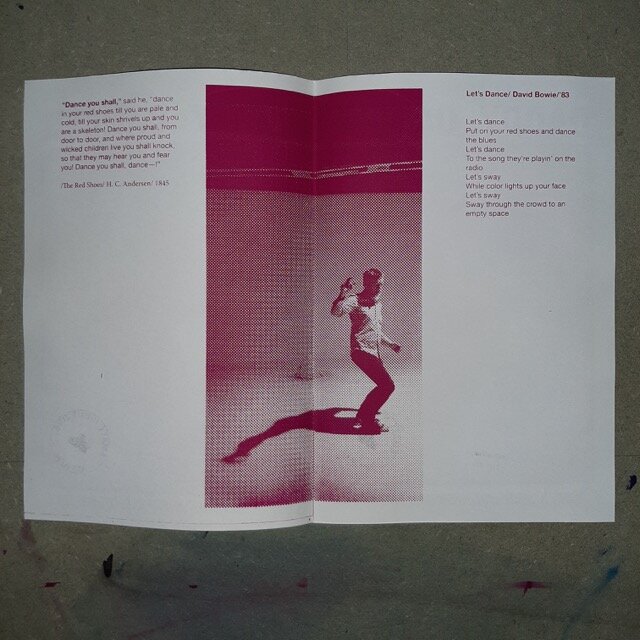

““Dance you shall,” said he, “dance in your red shoes till you are pale and cold, till your skin shrivels up and you are a skeleton! Dance you shall, from door to door, and where proud and wicked children live you shall knock, so that they may hear you and fear you! Dance you shall, dance—!””

“Let’s dance

Put on your red shoes and dance the blues

Let’s dance

To the song they’re playin’ on the radio

Let’s sway

While colour lights up your face

Let’s sway

Sway through the crowd to an empty space”

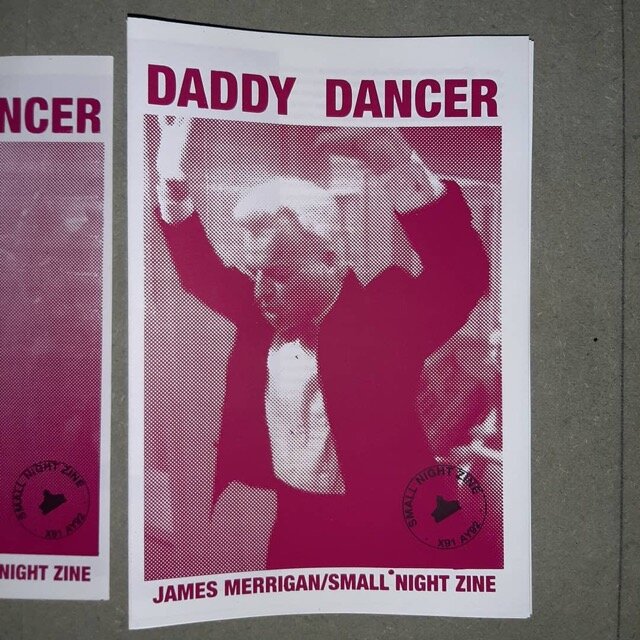

YOU call the performer ‘daddy dancer’ because it is easier that way. Daddy dancer calls his performance ‘Dance alone’, which is a little on the money for the times we live in. That’s why you have invoked a family to watch daddy dancer, a son and daughter mortified by their daddy dancing in a gallery for all to see. You don’t find it mortifying at all, daddy dancer’s dance; not like the way you have found performance art that was a little more self-conscious or masochistic mortifying. You are at peace with daddy dancer’s dance. It is entertaining. It is on point. A dance with a little more umph would have been too much; a dance with a little less umph would have not been enough. The planetary bodies of private and public orbit this Silverilocks in a universe that’s all wrong, rabid with anxiety and heartache. And here is daddy dancing in a gallery, with no invites, no VIPs, just a window – a large window – floor to ceiling, dancing under a spotlight, across the road from Centra during the 5pm rush, which is more of a creep these days. No dramatics. No knee slides. No triple twists. Just a body dancing, mind elsewhere, feet on the ground, head in the sky. A daddy dancer swallowed whole by his ears, down an eyeless chamber where a vacuum fills with music that daddy dancer bops to. What makes daddy dancer dance? Music? Mood? Exhibitionism? Company? A moment? You yourself either can’t or cannot dance; the distinction is hard to tell or accept. Daddy dancer can dance. You envy him that. Daddy dancer has music. You have nothing; no inanimate art objects to discern or distract from the body moving in sync with the music, the mood, the moment… company? That’s why you have imagined more, invented more, a narrative that includes... company. Without company what do you have?

As Tom Waits soulfully croaked, it’s “Closing Time.” A middle-aged man dances in a galley as the 2021 workday staggers to a 5 PM halt. Shirt, jeans, red runners, headphones, bristled from grey jaw to grey crest, the dancer dances unselfconsciously, a pale king in a white room. With no company or artist statement, we are free to pretend this dancer has children. Let’s name them Audrey and Leland for good reason. As daddy dancer dances he makes Audrey and Leland curl into ringlets of shame, like the daddy jokes he performed around their friends or the hopefully more. Shame! “Is he trying to impress them? Why does he have to speak, exist, dance!?” Audrey blushes while Leland nods in embarrassment. Daddy dancer moves; he sure does! He is not trying to impress with his moves, he is trying to feel, or turn inward to escape from the straightjacket of thinking or, he’s just dancing in a world of pretend, scheduled and awaiting an audience. Daddy dancer is in a gallery where pretend pretends to be true. The art objects are beside the point and pivot of daddy dancer’s fantasy. THIS IS NOT REAL! This is after hours, when screens oppress as black rectangles, powered off so the body can turn on. The dancer turns on his heel. The dance is a daddy dance. It is a dance of one when the couple is just a memory. Everyone looks on. No big show, just shuffles and taps and the clicking of fingers, something Audrey and Leland love most of all. When the dancer giddies up after a click of his fingers he almost takes off. Almost. But the floor is this dancer’s stim. He is a sweeping brush brushing on the spot, marking a spot, religiously not venturing beyond the mime closet of his masturbation. He dances; erect; alone. This is a pretend private dance gone public. The public watch from the gallery window – window shopping for a connection. They get sweet and sad and that thing the Greeks called pathos. Daddy dancer is wired up. Not wirelessly wired! Shame! He wears red All Stars. Shame again!! After 30-minutes of dancing his phone rings. The fantasy stops. He acknowledges the audience in a gesture of soft modesty that breaks hard on WALL No. 4.

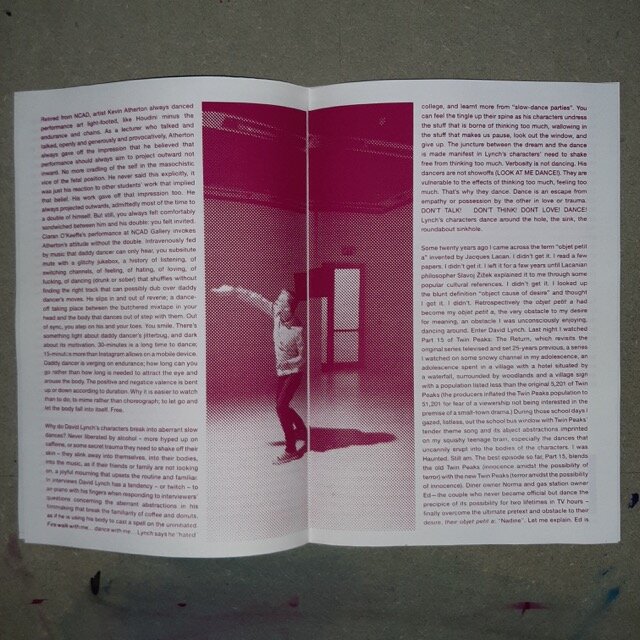

Retired from NCAD, artist Kevin Atherton always danced performance art light-footed, like Houdini minus the endurance and chains. As a lecturer who talked and talked, openly and generously and provocatively, Atherton always gave off the impression that he believed that performance should always aim to project outward not inward. No more cradling of the self in the masochistic vice of the fetal position. He never said this explicitly, it was just his reaction to other students’ work that implied that belief. His work gave off that impression too. He always projected outwards, admittedly most of the time to a double of himself. But still, you always felt comfortably sandwiched between him and his double: you felt invited. Ciaran O’Keeffe’s performance at NCAD Gallery invokes Atherton’s attitude without the double. Intravenously fed by music that daddy dancer can only hear, you subsitute mute with a glitchy jukebox, a history of listening, of switching channels, of feeling, of hating, of loving, of fucking, of dancing (drunk or sober) that shuffles without finding the right track that can possibly dub over daddy dancer’s moves. He slips in and out of reverie; a dance-off taking place between the butchered mixtape in your head and the body that dances out of step with them. Out of sync, you step on his and your toes. You smile. There’s something light about daddy dancer’s jitterbug, and dark about its motivation. 30-minutes is a long time to dance; 15-minutes more than Instagram allows on a mobile device. Daddy dancer is verging on endurance; how long can you go rather than how long is needed to attract the eye and arouse the body. The positive and negative valence is bent up or down according to duration. Why it is easier to watch than to do; to mime rather than choreograph; to let go and let the body fall into itself. Free.

Why do David Lynch’s characters break into aberrant slow dances? Never liberated by alcohol – more hyped up on caffeine, or some secret trauma they need to shake off their skin – they slink away into themselves, into their bodies, into the music, as if their friends or family are not looking on, a joyful mourning that upsets the routine and familiar. In interviews David Lynch has a tendency – or twitch – to air-piano with his fingers when responding to interviewers’ questions concerning the aberrant abstractions in his filmmaking that break the familiarity of coffee and donuts, as if he is using his body to cast a spell on the uninitiated. Fire walk with me… dance with me… Lynch says he “hated” college, and learnt more from “slow-dance parties”. You can feel the tingle up their spine as his characters undress the stuff that is borne of thinking too much, wallowing in the stuff that makes us pause, look out the window, and give up. The juncture between the dream and the dance is made manifest in Lynch’s characters’ need to shake free from thinking too much. Verbosity is not dancing. His dancers are not showoffs (LOOK AT ME DANCE!). They are vulnerable to the effects of thinking too much, feeling too much. That’s why they dance. Dance is an escape from empathy or possession by the other in love or trauma. DON’T TALK! DON’T THINK! DONT LOVE! DANCE! Lynch’s characters dance around the hole, the sink, the roundabout sinkhole.

Some twenty years ago I came across the term “objet petit a” invented by Jacques Lacan. I didn’t get it. I read a few papers. I didn’t get it. I left it for a few years until Lacanian philosopher Slavoj Žižek explained it to me through some popular cultural references. I didn’t get it. I looked up the blunt definition “object cause of desire” and thought I got it. I didn’t. Retrospectively the objet petit a had become my objet petit a, the very obstacle to my desire for meaning, an obstacle I was unconsciously enjoying, dancing around. Enter David Lynch. Last night I watched Part 15 of Twin Peaks: The Return, which revisits the original series televised and set 25-years previous, a series I watched on some snowy channel in my adolescence, an adolescence spent in a village with a hotel situated by a waterfall, surrounded by woodlands and a village sign with a population listed less than the original 5,201 of Twin Peaks (the producers inflated the Twin Peaks population to 51,201 for fear of a viewership not being interested in the premise of a small-town drama.) During those school days I gazed, listless, out the school bus window with Twin Peaks’ tender theme song and its abject abstractions imprinted on my squishy teenage brain, especially the dances that uncannily erupt into the bodies of the characters. I was Haunted. Still am. The best episode so far, Part 15, blends the old Twin Peaks (innocence amidst the possibility of terror) with the new Twin Peaks (terror amidst the possibility of innocence). Diner owner Norma and gas station owner Ed—the couple who never became official but dance the precipice of its possibility for two lifetimes in TV hours – finally overcome the ultimate pretext and obstacle to their desire, their objet petit a: “Nadine”. Let me explain. Ed is married to patch-eyed and mentally disturbed Nadine. For a brief interlude in the original series Ed and Norma get together when thirty-something Nadine loses her memory to regress into a teenager in the possession of superhuman strength. Everyone is ‘happy’ until Nadine’s memory returns in the concluding episode. In The Return, Nadine confronts Ed at his gas station with a golden shovel (long story) and releases him from his marital obligations. A gawky Ed rushes to the diner, waves and strides towards Norma to tell her in his country and western timbre that he is free – they are free. Norma snubs him momentarily by continuing with a business appointment in a booth at the far end of the diner with a man that Ed suspects is also a love interest. Ed – a still reed in a storm – orders a coffee, takes a seat at the counter after a few sidelong glances with Norma that reciprocate disappointment, to then slip into a thousand-yard stare. Closing his eyes to inhale and hold the seconds, Ed braces against the suspended moment when Norma will either reject or accept him. “Same again Sam!” The objet petit a is not the object of desire (Norma or Ed) but the delay or suspension of attaining the object of desire. They are entangled, desire and its obstacles, fusing as surplus enjoyment. Ed’s freedom from Nadine immediately finds its substitute in another ad hoc objet petit a – anything to prolong the obstacle and object cause of their desire, a desire that will become void alone. This scene, although it has the elements of what could turn into the dogma of a Hollywood embrace overseen by the cheers of an overenthusiastic crowd, is anything but. Norma and Ed finally seal the union with a kiss, somewhat ironically to Ottis Redding’s I’ve Been Loving You Too Long after dancing too long to Jim Morrison’s lyric I’ve got this girl beside me, but she’s out of reach. I give them 6-months. Tops.

Yesteryear daddy dancer’s dance would have been a quirk; today it is a quirk and more, stepping in tempo with the mood and moment that will become indelible when the need to dance will be replaced with want once again. Daddy dance is a glitch in a glitch, a meta moment that looks at itself looking at itself, dancing with itself, within it-self, it and self entangled in the pandemic abstractions that are impossible to verbalise. Dancing is the best you can do, all you can do. Minus the ‘daddy’ – but not the dance – you are left with a dancer dancing alone, swaying through the crowd to an empty space (David Bowie). Empathy turns to empty as the emotional oxymoron between dance and alone clashes, leaving us to imagine a dancer, in a bedroom, just out of the shower, where he wallowed in water and whiskey, to end up dancing with the memory of someone else. To dance is to dance, tout court. However “dance” accompanied by “alone” can only mean one thing, not two!