Mercurial Richard Mosse

“The aesthetic problem is not at all about beauty. It is the experience of a common world, and who is able to share this experience. That is why, for me, politics is aesthetics before art. ”

“Together these elements create an unsettling yet mesmerising experience that aims, in Mosse’s words, “to implicate the viewer within the work’s gaze, to force the viewer to confront their own participation on many levels”. ”

The Butler Gallery's use of the not-so derivative adjective “mesmerizing” for their Richard Mosse exhibition is perfectly poised. It follows their use of “unsettling” to describe Mosse's 52-minute video installation Incoming (2017) presented at the Butler’s new home at Evan's Home Kilkenny. Usually it's best to ignore such promotional adjectives for, of all things, contemporary art, which most of the time endeavors to flatten experience, not hyperbole it. That said, the word “mesmerizing” could not be a better conjunction to “unsettling” to describe Mosse's controversial and episodic redescription of social trauma that conflates politics with aesthetics in the heart of humanitarian darkness.

At Butler Gallery the majority of the space is blocked off – partly motivated by COVID-19 restrictions and presumably Mosse's insistence to only have front row seating – to create a one-way corridor that guides you to the double-height and triple-long room. There, momentarily adjusting to the deep darkness and the tonal strangeness playing out on the double-height screens that span the room, 1… 2… 3….. you find yourself in the cockpit of Mosse's mercurial vision, the plane spinning in a slow silver haze. The experience of these three screens up close is that you cannot pull all three together. It's experiential not contemplative; it's political not aesthetic. It has the oompfh, vibration and girth of a rock concert; “rock star” Mosse (as one newspaper journalist referred to the artist recently) is behind the camera, but still larger than life in the choices he has made to look at humanitarian crises from inside out.

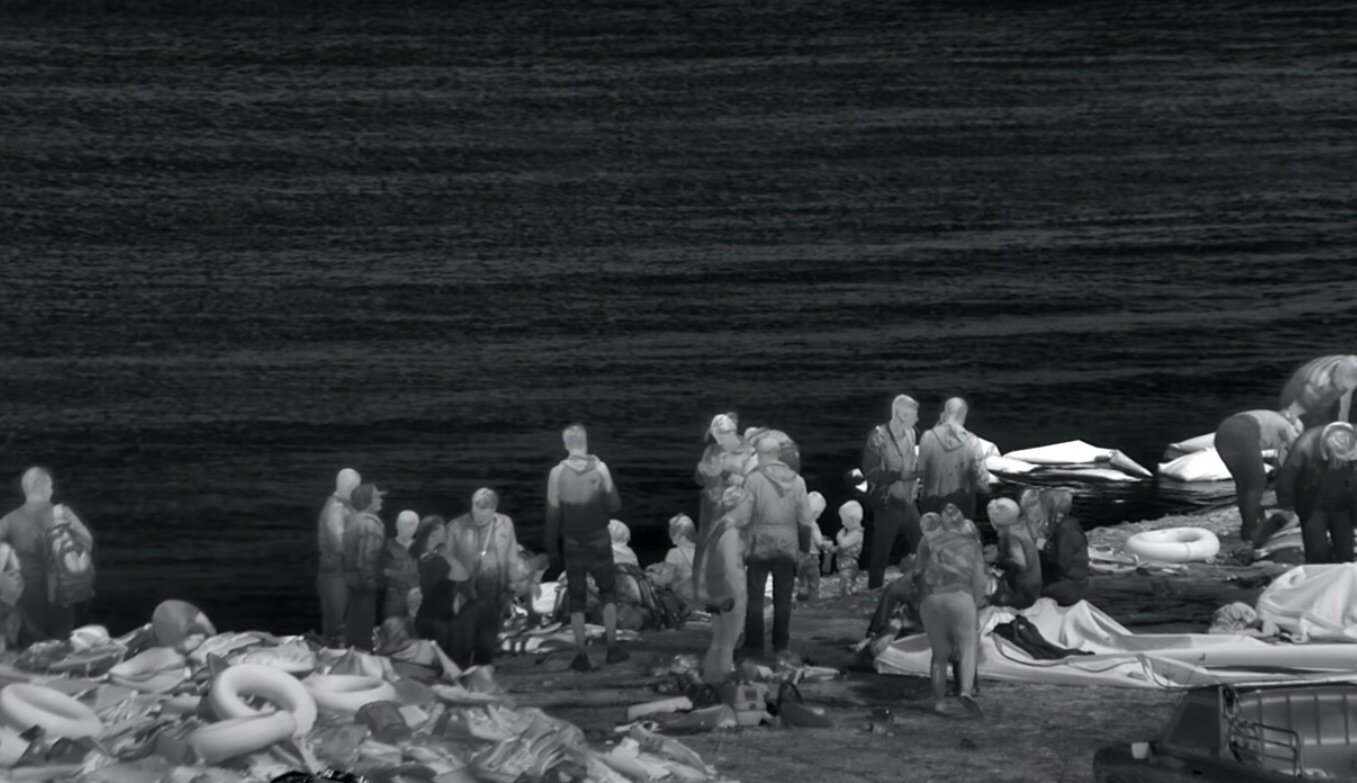

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

This time Mosse's lens is aimed penetratingly at the European refugee crisis – a long-lost memory before the temporal black hole of the pandemic – with the use of a military-grade thermal imaging camera made by a European multinational weapons company. The resulting image is monochrome grey and glacial in form, with a texture and pace that speaks the audio-visual language of contemporary art. The camera (or weapon) registers body heat, rendering the world transparent or reflective, ironically like a block of ice. When the same camera cannot render reality due to extreme heat or cold (jet engine flames, camp fires, a lit cigarette, or the cold ocean that acts as both barricade and vehicle to another life for the refugees), violent fissures of pure white or droplets of jet black rend this alien world apart. It's a beautiful thing, a mesmeric thing that Moss has appropriated and repurposed. So beautiful and new that it almost eclipses the subject of the refugee crisis being documented. Frame by frame the subject moves beneath this space blanket like a latent trauma, both present and absent below its silver folds. Like through a sniper's lens, Mosse's camera crops and targets in a narrow field of vision that looks through rather than looks at, ending up in what some have described critically as the Irish artist's “aestheticisation of suffering”.

And that is where unsettling enters and mesmerising exits to conjunctively contrast the political subjects of Mosse's work with the poetic objectification and obfuscation of that same subject. Simply put: the subjects of Mosse's photography and film are unsettling in terms of the contemplative, distant and passive aesthetic gaze in times of social suffering and political unrest. And all this plays out in a high-end presentation of that reality in the unreality of the gallery space for the consumption of the small artworld. Mosse’s film installation Incoming is both unsettling and mesmirising so you can suffer it – in what the artist describes repeatedly in interviews as the viewer's complicity – and enjoy it.

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

The use of unsettling first and mesmerising second is interesting, in the way that unsettling has critical cachet whereas mesmerising is for your entertainment. What is being claimed for Mosse's work is that it is first and foremost critical, but it is also a feast for the eyes. It is this balance between the ethics of its criticality and the aesthetic spectacle of its ambitious delivery – most art institutions do not have the technical resources to present this new work – that some have called into question. Further, if you look deeper into the definition of mesmerise – to “bring into a mesmeric state, hypnotise” – you will discover that mesmerise relates to ‘mesmerism’, “the doctrine that one person can exercise influence over the will and nervous system” of another. It is through this hypnotic state that we have to confront and contend with our thinking, feeling and opinion about what is really playing out beneath the aesthetic gloss in front of us.

The conceptual groundwork for Mosse's practice is revealed via his interviews (there’s several on YouTube for this work alone) wherein the artist openly discloses the how? and why? of his working method, which most to the time begins with the repurposing of military-grade technology, the very tools that keep war-torn countries under vigil and thumb. And you can imagine and understand Mosse’s glee, like every artist, when he comes across a medium that can direct his hand in the expression and motivations of his aesthetic needs, wants and ambitions. Of course, like every artist working in the language of contemporary art, Mosse tweaks and tinkers with the technology so it speaks with a tonality and pitch that is understood by the viewer of art.

Guradian art critic Adrian Searle on hearing Richard Mosse being awarded the Deutsche Börse photography prize in 2014.

But rather than just release his film and photography into the world for the viewer to decide, Mosse ends up defending his practice to journalists who throw the obligatory and stray never-followed-up ethical question his way. The minute you defend your art as an artist you have lost the argument, especially when the questions lobbed are based in ethics – and especially when the artist in question is repurposing and lugging the same weaponry back to war-torn countries where this technology is used to keep “insurgents” in check, and all this with a mix of photojournalistic zeal and conceptual side-stepping. (Perhaps this is the reason behind Guradian art critic Adrian Searle’s critical and reductive Tweet in 2014 on the occasion of Mosse being awarded the Deutsche Börse photography prize – See picture above.)

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

Neither an activist nor a “dry conceptual photographer” (his own words), Mosse's work “elevates” photojournalism beyond quotidian news media and cerebral contemporary art towards the empyrean where run-of-the-mill reportage is transformed into sublime feeling. There is something religiously perverse about this transformation that leads to an aestheticism and voyeurism that sheds the skin of reality to reveal its ghosts rather than its essence, an aesthetic ghost that haunts long after you have left the gallery – I still have magenta in my eyes a decade on from Mosse's film and photography of the Congo. Mosse might rightly respond to this aesthetic perversion and viewer possession as the very purpose of art, to unsettle and inject the viewer with feeling, even empathy, through the aestheticism of reality and the “distribution of the sensible” in a common world where complicity is a given. His work (in my experience and address here) does not instil empathy in the viewer, it seduces in its efforts to induce feeling. Its high-endness, its showmanship, its glossing over the brute pragmatism of the originary purpose of the technology with beauty and distance edited with instances of disgust does not squeeze a single tear from the eye. There is an implicit disinterestedness in the aesthetic that comes from the technology and the editing that reveals this as an aesthetic passion not a political project. Again, art that deals in politics within a wounded and vulnerable public sphere is bound to stir these feelings in the viewer, but to what end? What is the motivation? To bear witness?

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

French philosopher Jacques Ranciére writes that bringing awareness to something is a form of inaction… what do we do with our awareness? Not to be glib but all we can do it seems these days is post our inaction virtually on social media. Experience is the motivator for action, whereas the introjection of an experience that is not ours in the first place is a type of masochism or ego filler. Is Mosse packaging suffering as art, or art as suffering? If the artist’s motivation is for the viewer to bear witness to human atrocities so they might feel something, where does that feeling go in a pragmatic sense? (I think here of the Quaker tradition of bearing witness to humanitarian crises in situ as a form of action/inaction.) If Mosse's motivation is for the viewer to bear witness at an aesthetic distance of contemplation in the safety of the gallery, then he has indeed elevated photojournalism to that of the nineteenth century idea of art (or today’s for that matter) when the passive inaction of men of taste in front of the artwork was/is a signifier of class. Moreover, if art is an individual experience, how can mediated transformations of reality that lean towards sublime beauty end in the transformation of the individual? The highly aesthetisced experience of Mosse's art, fraught with pleasure (jouissance) can only compel dissociation not empathy, paralysis not action. It’s art after all, not activism.

This body of work by Mosse arrived late on our shores; Incoming premiered in London at the Barbican Curve in 2017. And like Mosse's Venice Biennale contribution Enclave, which redescribed the war-torn traumas of green Congo in sweet magenta, this work resurrects the same tension between politics and aesthetics that critically bruised the reception of Enclave. For a decade in terms of artworld visibility, Mosse has continued to test the same tensions between politics and aesthetics in his film and photography, a body of work that the New Yorker coined – in a rather detached but perhaps very accurate phrase – “conceptual documentary”. The same antagonisms remain between the ethics of Mosse's gaze in the context of the humanitarian crises which he continues to pursue and peruse under the gaze of the market-led artworld. Mosse almost manifests the contradiction inherent in Ranciére's philosophy of aesthetics, which propounds the idea that aesthetics – not related to art but politics – is an emancipatory gesture in his theory of the “distribution of the sensible”; whereas aesthetics in relation to art is a relationship that speaks of passivity and inaction, disinterestedness and distance in relation to the social mores of inequality that humanity enacts in the name of politics, democracy or otherwise. Mosse has found a space wherein these political antagonisms, binaries and spaces of argument are almost vanished away by the beautiful gloss of his work.

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

It needs to be emphasised that “beautiful” is meant here in terms of something that disrupts, not only the subject that is being documented in a quasi-photojournalistic artistic way, but also the idea of beauty as something that arrests our attention and satisfies the senses, whether the magenta of Enclave or mercury of Incoming. The beauty that is being presented here is something that torments binaries. There are moments here that are dramatic and explicitly uncomfortable, moments that will offend and enrage, like the family who, on experiencing the moment when the surgeon cuts out the humerus bone of an unidentified body of a dead child for the purpose of DNA matching, left the gallery in moans of dismay and groans of anger. This may be a blockbuster, but best to leave the popcorn at home.

These highly charged, visceral and emotional moments that Mosse edits into his film work have a spectacle about them that is invasive, insidious and questionable. Under the silver gaze of this weapon of a camera, some visceral moments are almost made tender. Like the soft, slow and white movement of the surgeon's hand as he brushes back the tarp to reveal a child’s skull followed by the piercing grind of the bone cutter, a sound that you feel in your bones like the winter cold that gets into your body after overexposure. Sitting here, watching the family led out of the gallery by a parent, I wonder if these moments are to be endured rather than experienced. You cannot empathise with moments like this because the imagination begins to colour in the silver sheen with horror. You are also trying to decipher what exactly is happening beneath the veils of absracted image and sound. You want to know but don't want to know. From the surgeon's perspective this is a routine operation; from the detached viewer's position vis-á-vis the cold gaze of Mosse's camera, routine is rendered gruesome. Hannah Arendt “banality” fights with Hollywood spectacle, and you question why the vacillating tones between what George W. Bush Junior exclaimed before America invaded Iraq, “shock and awe”.

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

The awe is easy to recommend here. Many journalists have waxed lyrical about Mosse's aesthetic while at the same time apologising guiltily for being seduced, as if they have forgotten what has played out on the screen before them, like all of us four years on from the peak of the refugee crises in terms of news media coverage and social media cri de cœur. And when you go to a gallery, especially in this time of booking a time slot, you want to be seduced. And MOSSE seduces. This world, far, far away from his magenta Congo of boy soldiers, is a mercury moon with mercurial shifts in emotional and formal tones; a place where gravity, light, shade act differently; a place of white fire and grey ice, so sculptural that the forms will arrest the attention of those enamoured with such things as texture, form and light – such as artists, such as Mosse, such as me. The eyes dilate and contract as forms grow white hot and black cold, creating feelings of enrapture and estrangement. It's silly to say, but just how the thermal camera renders metal is seductive – there's a gloss that's Daft Punk incognito and fashionable. Then there's moments when bodies, rendered small on tiptop cliffs overlooking the blackboard ocean look like willow-thin drawings. It's difficult to describe this new image of the world Mosse has extracted from such an unromantic machine, a weapon that penetrates the world with the sole purpose of seeking, targeting and destroying from ridiculous distances. Especially when the artist gets in close to a body that, in the end, is not resuscitated, which the sound of a beep-beep heart monitor drives home almost too literally. The sound plays its part here but most of the time it hides behind the images, a droning core rarely going off emotional course except for one upbeat moment when refugees find refuge in the conjoined play and limbering of their bodies in some tarmacadamed and fenced-off outdoor waiting room. Mosse has given us a new way of seeing the world. All that is left to do is to either consume it aesthetically, critically interrogate the motivations behind it, or find a middle ground where politics and aesthetics make sense.

So what are the ethical issues with regards to Mosse's growing filmic and photographic oeuvre. If we look at it theoretically and we think about Mosse as a political artist who is working with subjects that are vulnerable and periodically neglected by the full gaze of the news media until it is too late and humanitarian crises become entrenched and unmovable, and his relaying of this rare image of the world in a new form by repurposing the very weaponry that governments use to control its citizens, what we are left with is a double bind between the subject and the method in which the subject is being documented. The artworld is once removed from the world and twice, three, many times removed from the worlds where Mosse finds himself with weapons of mass surveillance. Whether in the Congo, Syria or the refugee camp in Lesbos, Mosse's work exists on the back of societal traumas, it is dependent on them and the very tools of control and surveillance that perpetuate these humanitarian crises, that hold them in place. What is being documented here is the refugee's transience, their homelessness, their waiting, their helplessness, their trauma, their deaths with the help of the weapon that helps to perpetuate it all.

Still frame from Incoming, 2014-2107, three-screen video installation, 52 mins 10 secs, with 7.1 surround sound. ©Richard Mosse

If the aesthetic is, in Ranciére’s terminology, not concerned with art appreciation or distance but rather a sharing of the sensible world with the implicit, critical and political question as to who can share that common world, a world without the entitlements of gods or kings, then where is the sharing in Mosse's work, wherein the distant eye of the camera and cameraman is not reciprocated by the subject (object) of the refugees? This unreciprocated watching plays out violently and voyeuristically in the scene which documents the warehousing of refugees in makeshift partitioned rooms with no ceilings. Mosse monitors on-high from an invisible distance. This scene, rather than the thermal theatre of rescue, resuscitation, death or exodus mark the mind, like the way night-dreaming redescribes the desires and images that we never notice registering during the day. We can grimace at the terrible beauty of the theatre and move on, but these scenes leave slow, residual traces like the snail from the night before. Art can be successful but also damaging in the same instance. The ethical contradictions within Mosse's practice are manifold, and perhaps unfairly mined from his interviews, where there is a dialectic at play between his formal ambitions and the emancipatory rhetoric of his social ambition to invert the passive gaze of the art viewer; and that somehow through the will of his aesthetic the viewer will recognise themselves, their own participation and complicity with what is unfolding in the world at every given moment, as Noam Chomsky has voiced time and again in his investigative research of the humanitarian crises in East Timor, Palestine and elsewhere.

Personally I don't recognise myself or my complicity when watching rescuers hauling children from sea to ship. Besides wishing it never happened, I wish for their parents to be there waiting so they could hold them tight with love rather than efficiency. —James Merrigan

Through 29 August 2021