Long-Form : in conversation with Mark Swords

Joaquin Phoenix reading Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966) in sex shop; from Joel Schumacker’s 8mm (1999).

Context : Mark Swords

Every now and then Mark Swords and I meet for a coffee to discuss art-making and the Irish art scene in a small coffee shop in Gorey Town: we both tutor at Gorey School of Art (GSA). We usually end up talking about painting because Mark Swords paints and I'm into talking to painters about the stubborn nature and nurture of painting.

Recently I brought up a painting that Mark painted in 2012 titled Forgery (pictured below); a painting I fell in love with when I co-selected it as part of the group exhibition 'Making Familiar' at Temple Bar Gallery and Studios, Dublin.

The painting in question wasn't the type of Mark Swords painting I had come to know and accept as a 'Mark Swords' painting at the time. Sure, the hallmarks were there—a collage of shapes somehow falling together and falling apart like a teenage summer romance. But this one-off painting felt like it had escaped the studio prematurely, looking more like a working palette for a more resolved painting that was already out in the world somewhere. But unlike some painters not noticing their palettes performing better than their paintings, Mark saw enough value in this thing to pack it into the car and put it out there in the 'maybe bunch' for the exhibition.

What attracted me to this painting first was... it was active, a work-in-progress. Primary colours were unmixed in parts while blue, yellow and red became the under-crust of shitty browns elsewhere. There was an erotic slit down the middle of the primed slab of wood on which these colours sulked and played together. It was a painting by a man who wanted to be a child, or a child who wanted to be a man, or a little of both: it was a transworld of thresholds. It could have went either way but we would never know because Mark stopped at the wrong moment. It was a maybe. It was an almost... it was almost a Mark Swords.

Five years on that painting still drops in on my brain. My first memory of the painting is of it propped up against the gallery wall among a lineup of certainties but I picked this wife beater. It jarred the whole exhibition, even with Paul Doran's paintings alongside; but it gave me joy and it formed a stubborn memory that I will probably never shift.

Mark's current solo show at TBG&S has a whole lot of the stuff that made Forgery so obstinate and verbose and good. As promo for a talk that he was giving on the show at TBG&S Mark posted an in-profile selfie on Instagram in which he is performing a 'silent' shout or scream or yawn against a shelf of books. It made me laugh and balk much the same way his paintings make me laugh and balk.

In the coffee shop I brought up the question of 'response' to Mark's work at TBG&S. He had got some; during the opening and during the talk. He was relatively happy, considering what he had said to me before about the "100% experience" of process versus the 'eh' (my exclamation) of everything afterwards.

So I shared my experience of the exhibition with him—no questions just my experience because it's less evasive. First, it reminded me of Forgery. Then it made me laugh inwardly, like an in-joke for one. I brought up comedy, he brought up Stewart Lee; he brought up carnival, I thought Mikhail Bakhtin; he brought up notions of coyness and discovery and necessary ambiguity; I brought up exhibiting explicit self-awareness and sincerity; we brought up a whole lot of 'what ifs' and I said his show was a criticism of painting. He was about to respond but lunch was over.

After lunch we walked back to GSA and I suggested we make this into an interview that started mid-sentence without all the introductory niceties.

Here it is.

Mark Swords, 'The Living and The Dead', Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin; 15 April - 17 June 2017: photo: Peter Rowan

James Merrigan: Before I get to the question of your show at TBG&S being a criticism of painting... no, forget that, is your show a criticism of painting? Maybe you could describe what you have done in the gallery?

Mark Swords: The show is a collection of work (some 30 pieces) made over the last three years, but, more than that, it is an experiment in terms of installation that has been developing in my head for the last couple of years. Nearly all the work in the show has been hung against various patterned and painted wall coverings. The paintings are quite close together and so there's not a lot of space in the show; it looks very dense and complex.

The answer to your question is: no. This show is probably many things before it is a criticism of painting although I would acknowledge that I make work as much informed by my criticisms of other artworks as it is by what I value. So, for example there are a lot of approaches and techniques which are absent from my work because I feel that they are not part of what is exciting and interesting about painting. I think many artist's work can be seen as putting forward a case for their position and so, by implication a case against what they do not value.

Maybe painting more than other mediums has all this space around it. Space that focuses our attention on the artwork which reflects some aspect of the world (depending on the artist's intentions). And that is great. I have enjoyed that in the past and probably will again in the future. But for some time I have been interested in experimenting with this and wanting to deny all that space. I was curious to try to mimic the world and the way we experience it—everything together, unedited, unpredictable, exciting, contradictory.

But I am interested in how it could be viewed as a criticism of painting? Is that because of the paintings themselves or the installation. Or, more appropriately maybe, both; and the ways in which the installation gets in the way of viewing the pieces in a more conventional way?

JM: Perhaps my question about your current work at TBG&S being a criticism of painting should be rephrased with the help of your response about the denial and replacement of the negative space that usually surrounds painting in the gallery with your use of this carnival backdrop of colour and texture. This is a big twist in the tale of what I have come to accept as a 'Mark Swords' exhibition, and can't be waved away as merely an experiment, especially in terms of a painter who has developed a recognisable and established identity over a good many years and is also represented by a gallery that deals not just in objects but the luxurious white wall that isolates painting and gives it its object value.

However, the notion that you're denying the conventional breathing space to experience and judge the objet d'art that is painting as a criticism of painting could be transferred to the notion that this display is a criticism of Mark Swords the Earlier, the Previous, the Younger, Lol? Further, you have placed one painting in the gallery that performs in splendid isolation. Is this a lonely signpost to the past?

Mark Swords, 'The Living and The Dead', Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin; 15 April - 17 June 2017: photo: Peter Rowan

MS: Yes, there are criticisms of my previous work in 'The living and the dead' but not condemnation. That is probably natural for an artist and is certainly true of any new body of work I have made.

The most significant criticism of "Mark Swords the Earlier" as you put it is not the use of the gallery walls per se, it's more the inexperience and naivety of not questioning the conventions of exhibitions. I am starting to think that an artist can hide behind the conventions of the gallery; that, and ambiguity.

I remember listening to someone who had been present at early peace talks between The Provisional IRA and British representatives and they used the term 'constructive ambiguity' in relation to language. I thought it useful to re-appropriate that term to art-making—to create space and room for different interpretations. I think I have done this a lot in past exhibitions without consciously doing so. In my current show there are a number of different things I am doing to address my self-criticisms and my attempts to be more up front about how and what I am doing in my work: writing directly onto the paintings, an openness to subject matter, and the installation itself to name a few.

Mark Swords, 'The Living and The Dead', Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin; 15 April - 17 June 2017: photo: Peter Rowan

But I think you may be underestimating the importance of experimentation for me. I don't mean to diminish the installation of 'The living and the dead' by describing it as an experiment ("merely an experiment”), but it began as an experiment in the studio and progressed into something more substantial as it became an abstract depiction of a place. This is the same thought process (of trying and testing) and the same artist who made Forgery, the painting you discussed in your intro. Most of the reasons I made that piece were to do with the things (I thought then) one should not do as an artist: so, appropriating another person's decisions about form and colour; celebrating crudeness in terms of execution and allowing myself to make a piece of work that did not 'fit' with its peers—a hiccup. And I should admit to an attitude of testing rules, poking at my own assumptions or, as other people may see it, being mischievous; a miscreant perhaps.

I am immediately anxious about the tone of self promotion in what I am saying here, maybe because it is written instead of spoken. I am not operating under the assumption that what I am doing is significantly ground breaking or challenging or that these things have not been explored more succinctly by better artists many years ago. Sometimes art history can excite and embarrass us and make me feel very conservative.

JM: Okay. Let’s take all this from another angle by discussing something less cerebral and critical—pleasure.

In previous conversations we have discussed the pleasure in the process of making paintings. When I was with your work in TBG&S I got the same giddy feeling that I get sometimes when I visit an artist’s studio. I can only call it surprise mixed with pleasure. I don’t get this feeling often in the gallery space. I got it from Mary Heilmann’s paintings at the Whitechapel Gallery London last year. When I don’t get it I put it down to the studio experience vs. the gallery experience: the studio being a place of play and risk, experimentation and excess; the gallery being an endpoint to that play and risk, experimentation and excess. The exhibition is of course a necessity because all that play and risk, experimentation and excess can only end up destructive if it doesn’t have an endpoint where the process is framed and isolated by the white walls of the gallery to be appreciated as a cerebral and emotive event and so forth. But I have to admit that sometimes the artist’s studio reflects all the excess of the “unedited” world that you speak of better than the exhibition ever could.

Your work at TBG&S (in my experience of it) had the feeling of the artist’s studio about it. The play and risk, experimentation and excess wasn’t as distilled as it could have been if you hadn’t denied so much white-walled gallery space and substituted it with this carnival of colour. There are paintings in that big mattress of paintings at TBG&S that wouldn’t have made the cut of a Mark Swords The Earlier exhibition. That’s why when you mentioned “carnival” the other day as defined as the collapsing of hierarchies and societal norms I thought immediately of Mikhail Bakhtin. I wrote an art college thesis on Bakhtin’s carnival in relation to painting and other stuff back in 2004. What I took from Bakhtin’s theory of carnival (aside from the political upending of society) was the pleasure one gets when the playing field is levelled and the rules are broken.

Stewart Lee on stage.

So in short what I am wondering is, by experimenting in this way at TBG&S and breaking a few of your own rules in the gallery space, did you experience pleasure doing it? And if so, how can you go back to giving the white wall more territory in the gallery when you have ‘danced with the devil’—a reference to a line that Joaquin Phoenix delivers to Nicholas Cage in the Joel Schumacher film 8mm (1999): “If you dance with the devil, the devil don’t change. The devil changes you.”

MS: In an artist interview I enjoyed recently the interviewer was talking about meeting an ex-girlfriend whom he had once loved but when they had met 20 years later they hardly recognised each other. He surmised that deeply intimate things change one’s character forever. This was also said in the context of discussing how it is possible to draw or paint something so often that it can lose its meaning and become just a shape to be used or arranged.

You are asking (I assume) if I can make an exhibition in the future which would be like one of my previous exhibitions, and the answer is, no, I cannot. And I am wondering (as I write this) whether I would want to…?

Everything we do probably changes us. I have worked very hard for a couple of years on this show and through reading, thinking and reflecting it has become significant for me and has, no doubt, changed the way I will approach being an artist. But I would have to say the same of previous bodies of work.

I am very pleased by your suggestion that there is a sense of the studio about my show. This was certainly something I wanted to achieve. For a while now it has bothered me the way an exhibition can so alter an artwork that some of the life is taken out of work when it goes on show; paintings that once excited can deflate in a different context. This is not to say that I wish to exhibit my studio (I did that kind of a few years ago at Wexford Arts Centre). It’s more that I want to achieve the feeling of play that occurs in the studio in the exhibition.

Mary Heilmann, ‘Looking at Pictures’, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2016

I wonder was it the ‘playing’ that you responded to in the Mary Heilmann show? I think that kind of testing and questioning is in her work and so I wonder how much of this is about the execution of the work and how much is about the staging of the exhibition? It’s worth saying that there was a lot of white wall in that show. I think the studio (play, risk, experimentation and excess) is in that work; those paintings are about that stuff and that’s how the studio is in that show as it were.

I don’t know Mikhail Bakhtin’s writing on Carnival but I found it coincidental to read that Bakhtin’s “… carnivalesque is tied to the body and the public exhibition of its private functions.” ( This is from Theodore F. Sheckels Maryland Politics and Political Communication 1950-2005 which I have NOT read). I admit to using this out of context but, isn’t there something in this description of the carnivalesque—the public exhibition of its more private functions—that is similar to the relationship between the studio (private) and the exhibition (public)?

I don’t know what my next exhibition will look like until I have made the work, but I would acknowledge that the experience of this show will be assimilated. I take hope in what I was saying about Mary Heilmann’s work containing all that stuff from the studio, especially if it doesn’t get polished out; and that what we are talking about is not white walls or coloured patterns. It is about intent and priorities.

JM: It was the ‘playing’ that I responded to in the Mary Heilmann show. It happened to another guy when I was there too: he was just standing there with the work and every now and then he would nod and smile and laugh to himself. I assume he was experiencing the same thing I was, the brain getting won over by the heart.

Heilmann’s paintings are so simple that you would never think them up, because we think we are so clever in our own heads but most of the time we are really dumb in our own heads. So I admire artists who can transcend their own intent and priorities and make something that has heart.

Your Forgery painting has an equal measure of head and heart, not to mention the title is powerfully tautological. Why would you copy such an ugly and awkward painting by poplar standards of beauty and skill (for the art audience I suppose). And isn’t all painting made yesterday, today and tomorrow a forgery—everything been done and all that. Forgery was also the odd one out in what you were doing at the time; it signalled a paradigm shift which I always get excited about in an artist’s work and which I think has manifested absolutely in ‘The Living and the Dead’.

‘Making Familiar’ (2012), Mark Swords and Paul Doran in conversation; Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin.

But Forgery is contained execution of all that stuff we have been talking about here; ‘The Living and the Dead’ is a mushroom cloud. And I wonder what’s the difference, between what you describe as the execution and the staging of painting? You are sacrificing a lot of good execution to the whole in the staging at TBG&S. There’s vulnerability being exhibited there too.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not suggesting artists should be continually destructive—Mary Heilmann achieves absolute optimism in a practice that keeps on testing the vulnerability and risk intrinsic to simple forms. Personally I want to experience the energy of the studio and the essence of the artist and the artist’s life in the work displayed in the gallery.

Since we have been having these conversations you have had a baby whilst also making art. But you have not just been ticking away, your intent and priorities have come to the surface of your new work, especially this new focus on painting at the expense of your previous sculptural tidbits. This thankfully proves me completely wrong that good and risky and playful art can be even made, and especially made if tethered to a life full of bigger and more important responsibilities than just art. That’s optimism, it’s even overly romantic, something that I know you are suspicious of with regards to the painter.

So your next show, if it is to live up to the head and heart of ‘The Living and Dead’ will either tease out or collapse what you have done here. You are in deep waters now. No pressure.

MS: In relation to the ‘execution and staging of paintings’: I only meant the making and finishing of individual works v.s. the staging—how those works come together in an exhibition. They can be (usually are) very different things. You have said that some of my paintings in ‘The living and the dead’ may not have made-the-cut in one of my previous exhibitions, and maybe you’re right, but I never really thought of them that way. As well as being individual works I was always conscious of what they were adding to the overall collection of pieces—a different noise, scale or imagery for example.

I took out Forgery today and spent some time looking at it just because your bringing it up got me wondering about its significance to what I am doing now, five years later. I still find it exciting (I was a bit surprised) and am still confused by its formal arrangement of shapes and dirty colours. I also feel that it comes very close to failing as it flirts with notions of badness/wrongness? Maybe most of all I think it has a vibrancy about it, as if it might start moving. It feels like a paused frame from an admittedly unlikely cartoon. I have a habit of describing it (and other works I have made) as “nasty”, which is a little disingenuous because that’s just a shorthand description for something I feel is beautiful despite its initial appearance. Lots of elements come together in Forgery: form, scale, intent, title and others to produce something richer, more challenging and more open for a viewer to experience.

You mentioned our conversation including Stewart Lee and his interest in pueblo clowns and the anarchism of carnival, but he is also interested in questioning his own work while performing it; playing with the form as it were. He talks about returning to stand up after a four-year break and how a contingent of his audience were giving him the benefit of the doubt because he had written a critically acclaimed musical in the interim period. It was, for him a case of well, he can’t be an idiot so he must be choosing to do his standup in this weird and monotonous way.

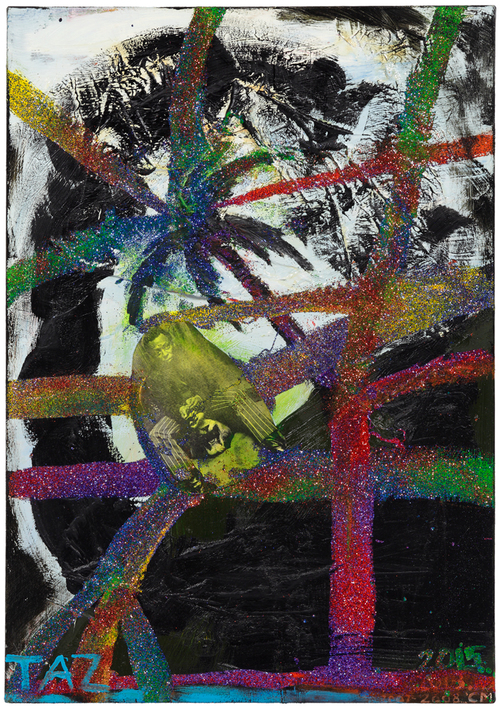

CHRIS MARTIN’S TAZ (2007-2015) portrays virtuoso Jazz musician Myles Davis amid palm trees and glitter and paint. The painting was on show in 2015 in the Chris Martin solo exhibition at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin.

I’ve also heard Lee speak apologetically about jazz musicians on a number of occasions to demonstrate a similar point. I think he says that in a jazz set there may be moments of clear melody or a demonstration of the musicians’ skill which, as much as anything else, serves to say to the audience: ‘It’s ok, we CAN play, we know how to do this but we are choosing to do it another way on purpose.’ I wouldn’t say this is what I am doing in my work explicitly but I do like these ideas and they have played a role in my decision-making. Strangely, Lee usually apologises for the Jazz analogy and for seeming pretentious (I don’t think he really means it). I don’t find it pretentious at all which might make me pretentious, but in a way I’m ok with that.

Mark Swords, ‘The Living and The Dead’, Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin; 15 April – 17 June 2017: photo: Peter Rowan

Thank you to Mark Swords.

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)