Beeple & NFTs: The $69 Million Question

“I feel like people have ruined [the label “artist”] by being pretentious douche-lords. ”

“My fifteen-year-old son showed me your work a while ago, this is fucking great, congratulations, you’re awesome. ”

“His images are not a deadpan commentary on the meaninglessness of social-media content, in the manner of Richard Prince’s Instagram replicas. They are an embodiment of it.”

“It’s a unique one-of-one piece, which treats his Instagram page kind of as a Duchampian readymade. ”

“This is basically a new era of art, participating in this auction is kind of making history. ”

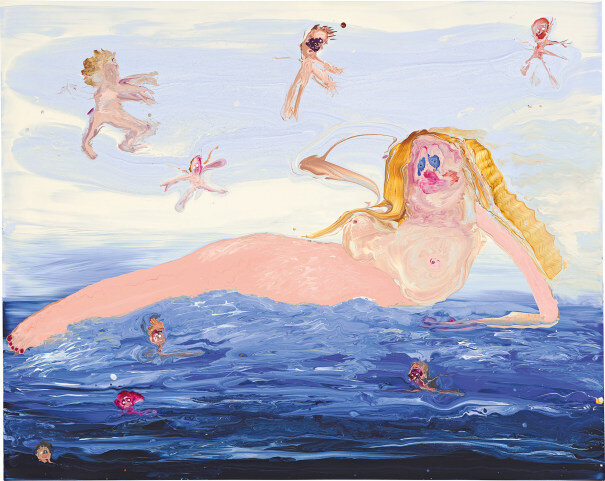

“In fact, one of the most profound tasks of art is to remind us that things, including people, can be understood for what they are in themselves, not just in terms of their exchangeability.”

MICHAEL WINKLEMAN IS 39. In the crypto-artworld Winkleman goes by the pseudonym “Beeple”. Up to recently he was primarily a graphic designer, with clientele including Elon Musk, Apple, Louis Vuitton, Nike, the Super Bowl. His day hobby, like most of us, is the churning of images on social media; in his idiosyncratic case, 5000 images day on day for the last 13+ years. He calls these daily social-media drops “Everydays” – in essence a creative-commons portfolio to build a client base for his designs (there's similarities with Andy Warhol here, whose career as a successful commercial artist preceded that of his shock transition into the New York artworld). In the crypto-artworld Beeple is a recognisable and revered artist, celebrated for his computer generated collages of ready-made models of everyday things, and his prolificacy and generosity in respect to sharing the how's and what's of his designs in the digital community. YouTube happy, Winkleman comes across as an open book in podcast interviews, wherein the interviewees have a tendency of first making the audience aware of his Midwestern modesty vs his predilection for the F-word. Winkleman refers to most of his art as “shit” with the promise it will one day get better. In 2020 – the pandemic has and will have much to answer for – he discovered NFTs. The rest is history (and perhaps the future). What happened next, in a matter of months, is what will be forever remembered as the infamous (and official inauguration of NFT auctioned artworks) Christie’s auction of Winkleman's mosaic jpeg for $69 million.

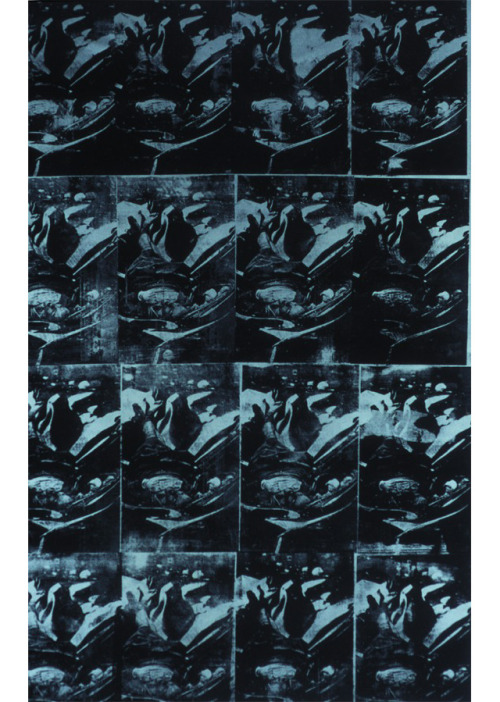

BEEPLE (b. 1981) "EVERYDAYS: THE FIRST 5000 DAYS” 2021. (Non-fungible token (jpg). 21,069 x 21,069 pixels (319,168,313 bytes). Minted on 16 February 2021. Sold for $69,346,250.)

Popular on Instagram – two million followers – Beeple's marketability was the reason why he made an NFT drop (more on that later) in the first place, and why Christie’s and the future buyer took notice. As we know the 3 P’s popularity, prolificacy and proliferation equates with marketability and fame these days. Looking through Winkleman’s portfolio (in full on his website), his images are the type of thing that would wrap nicely around a sci-fi/fantasy role-playing novel. He started his digital diatribe on Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter and Instagram when he was a twenty-something adolescent. A boy, a geek, Winkleman was someone who wanted to get better through doing, which he did under the pinch of a diurnal deadline – one image a day without fail even when he didn't want to. With all the images Winkleman made over the past 13+ years laid out on the table, the Christie’s auction of his mosaic jpeg this month reveals an artist who, primarily via the captions that accompany his images, has been sometimes racist, misogynist, puerile or fantastical (or a monstrous hybrid of all the above). Learning this we are left with the image of Winkleman entering his bedroom and burrowing away in his computer since 2008, dousing his naked self head-to-toe in the Internet and news media with no one to slap his hand when he said something untoward.

BEEPLE “THANK YOU” EVERYDAYS 23 FEBRUARY 2021 (DAY AFTER THE ANNOUNCEMENT DAFT PUNK SPLIT AFTER 28 YEARS).

Most of the time “art shit for yer facehole” (Beeple), sometimes visually nuanced, generous, even sensitive (above), Winkleman composes and combines ready-made models into visionary landscapes with timetabled urgency and obsessiveness — Winkleman's head may indeed explode if he misses a day. You could say he devours and is being devoured by the medium that he is interacting with, the Internet. The urgency, the repetition, the surface-level depth is the embodiment of what we have become as online consumers and consumed. The green acne of vomit emojis that swarm the comments under Jerry Saltz's Instagram post on the matter of Winkleman's earlier racist and misogynistic juvenilia is the perfect descriptor for what this is, but not in the way those emojis are being used. If Winkleman is not making art (with “human values”) as most in the “traditional” artworld agree, perhaps he is the object that everyone is lamenting is absent in the brand new crypto-artworld of NFTs?

BEEPLE “DAY 5000” EVERYDAYS 8 JANUARY 2021

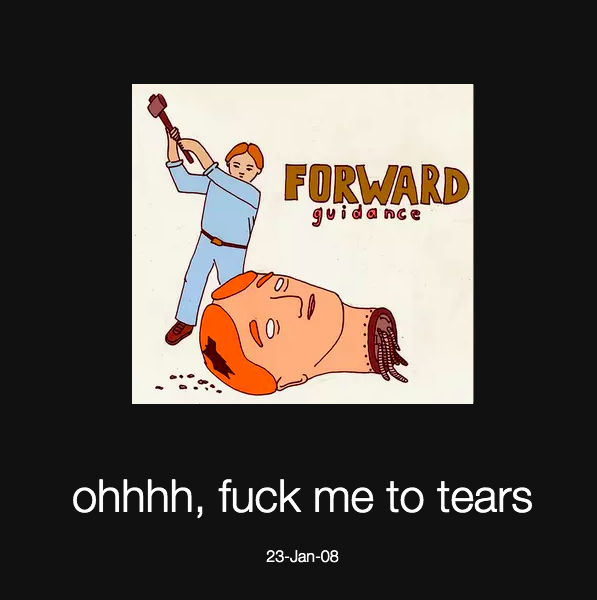

Winkleman lists Aphex Twin (who sold an NFT for €128,000 three days after Beeple) and his creative independence as an influence, a musician who started creating brilliant, abject symphonies in the privacy and freedom of his own bedroom. “What can one person and a computer do?... That has always been a really cool concept to me, because it’s the equalizer, in a way.” With no one looking over his shoulder, the PC police not knocking on his door, or good sensible friends to soundboard his ideas, Winkleman went all in and it all eventually came out. In February of this year – in yet another bedroom with a computer – Winkleman dreamt up the mosaic jpeg after Christie's rejected his first proposed image (above), which did not succeed in reflecting Christie’s “brand” in its vulgar singularity, but set as a tile within a diffuse and abstracted mosaic, did. The resulting artwork is constructed as a tabula rasa for the sole purpose of Christie’s auction; simply put, it was abstractly imagined with money and the burgeoning crypto-art market in mind. (The buyer did not preview the work!) With the sale Winkleman became the creator of the third highest sum paid for an artwork – all top three sold through Christie’s – behind Jeff Koons and David Hockney, but with a difference. Difference being: Winkleman's artwork is not an object in the “traditional” sense, but a digital file. Hence the reason for the criticism and confusion as to what this means for the art object in the, now, “traditional” sense.

BEEPLE “FIRST EMOJI” EVERYDAYS 2 SEPTEMBER 2021

Listening to Winkleman on the successive podcasts that have followed Christie's auction, he says he would not say the same things today as he has said in the past through his captioned images. But there is no regret or shame in his recollection of things he has said in the past, just dismissive responses about being “cancelled” by online culture. There is also no irony at play in Winkleman, irony being the artworld's way of being bad but not being really bad; irony being the scapegoat for political or social faux pas that might creep into the artist's work unexamined. Unchecked stream-of-consciousness is good and dangerous, especially when it is in full flow, uncensored, unperturbed, and with a validating audience. In this sense “Beeple” – a moniker repurposed from a toy Ewok which, when you cover its eyes it makes a “beep” sound – is more apt for Winkleman than he knows. There is something rollercoaster riotous about his 13+ years expulsion of imagery, as if, at the apex of a banked turn, Winkleman hopped onto an empty roller coaster pummelling downward through the Internet at enormous speed to become smeared in the colourful shit, piss, blood and protests of culture. Beeple is to the Internet what Michelangelo was to God. Like Warhol, is Beeple just an uncensored reflection or shadow of the present? Horrible to think. That said, we become the devil we admonish, the same way we wore clown makeup every time we named the ills of the world “Trump”. Beeple, also one word, could be named the embodiment of the media landscape that he devours. There is no critical reflection here in the onslaught and urgency of his output. When Winkleman talks about his images he refers to them as “weird” and “offensive” as if made during an out-of-body experience, a second self, or doppelgänger. Winkleman is echoing the words of psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott in such claims of “not me” possession, especially when working under the moniker of “Beeple”.

BEEPLE “BANNED” EVERYDAYS 9 JANUARY 2021

The contemporary art establishment has become “traditional” in the wake of this historical and perspective-changing sale at Christie’s; “Traditional” being the word that Winkleman repeatedly uses to refer to and defend against the furore from the contemporary art establishment, who have, in no uncertain terms, uniformly taken offence to the Beeple product and its market value, what is a revolutionary marker in the cryptocurrency art market and a white flag surrendering to the value of NFTs – non-fungible tokens, a “tool for providing proof of ownership of a digital asset”. Art critics have come out in a gaggle – Jerry Saltz, Sebastian Smee, Jason Farago, Ben Davis – to criticise the artwork, the artist (personally and professionally), and the provenance of the sale which, behind the traditional art facade of Christie’s auction house, looks like a pyramid scheme, the pyramidion being the buyer of the artwork, an “N.F.T. fund called Metapurse, led by Vignesh Sundaresan (aka MetaKovan), a Singapore-based blockchain entrepreneur” (New Yorker). In this flash flood of ink and talking heads, words and sound-bites have been regurgitated and bounced from one article to the next as critics fall over each other and fail to paraphrase this moment – monstrous or momentous – to exit the echo-chamber of what is a defining moment in culture: you can't see moments such as these if you are in such moments!

BEEPLE “VIBE CITY” EVERYDAYS 12 OCTOBER 2021

Always more critically nuanced in approach and with the added advantage of being always fashionably late, the New Yorker's Kyle Chayka cites and reflects on what the rest (New York Times, Artnet, New York Magazine) have to say after the fact, and by doing so, show the others up to be, in this instance, the same, in their reactionary and persecutors tone to what Saltz calls the “bald optimism” of Christie's, and the outright disavowal of Winkleman's artwork.

“Farago decried [Winkleman’s] work itself for its “violent erasure of human values” and reliance on “puerile amusements.” At Artnet, Ben Davis placed the crude political imagery of the ‘Everydays’ within the “Trump-is-a-Poopy-Head/Cheeto Mussolini genre” that has flourished in recent years.

”

Jerry Saltz's usual teenage-boy argo, with a prediliction for festishistic anatomical detail, zoom and crop in his art, historical or contemporary, is not far removed from Beeple's universe captioned “art shit for yer facehole” in his Instagram bio. Saltz lays blame on the agents of the art market, Christie's. Saltz has always been anti-establishment in his established role as chief and Pulitzer-Prize winning critic at New York Magazine, the paradoxical power position through which rebellion is confused with revolution, rebellion being a way in which to critique the game and the players while still staying a player in the game (Sartre). Winkleman is not dissuaded by this critical commentary which, for the most part, speaks his language. Subjects like Beeple packaged within the artworld – Like Jeff Koons, Kaws or Damien Hirst before him – form a critical free for all, one critic reading, assimilating and rebounding off the other in an effort to form new sentences (like me here) so as not to become irrelevant, creating an effervescent buzz, whereby the critic adopts the same language as their subject of critique, Winkleman being a subject who says things like this: “I feel like people have ruined [the label “artist”] by being pretentious douche-lords.” Both Ben Davis and Jason Farago point to themselves in an ironically self-effacing way in their articles, admitting that perhaps they are just being “sniffy” critics (irony, see!). Davis, who has written successive unbalanced critical blogs on Beeple as if he himself is being devoured by his subject, goes as far as aping Winkleman's own words to sarcastically describe his own opinion as ‘“fancy-dancy elite art homo” thinking’. This is what can happen in the school playground.

The New Yorker does not cite Sebastian Smee's piece on the Beeple sale in the Washington Post. Smee, a Pulitzer-Prize winning art critic, who, not in keeping with his usual turn-of-the-nineteenth-century tone, gets a little uppity in an effort to stoop down to his subject, by calling Winkleman's work a “Yawn” – Smee would not fair well in the same school playground as Farago, Davis or Beeple. Smee does not stoop far enough. Unlike Davis, who has perused inchmeal through the 5000 images that compose the mosaic, wherein, between the mouldy grouting, extracted one image after another from the whole to discover earlier drawings that were racist and misogynistic in message, resulting in Smee's “Yawn" turning into a collective grimace, from which the bit-part becomes the sum of Winkleman's message and medium.

BEEPLE “TOM HANKS BEATING THE SHIT OUT OF CORONAVIRUS” EVERYDAYS 13 MARCH 2020

Remarking in one podcast interview that the later work is “more me” and being “not fully conscious” of how these images come into being, says a lot about Winkleman's process, a process that has been valued in terms of time by Christie’s (13+ years of work offered in one bundled sale), and a process determined by time in the reactionary day to day self-imposed deadline to not get rich but to get better at what he does. In a podcast interview on YouTube in 2018, before NFTs, before Christie’s, when Winkleman was living comfortably off his freelance design work, just after moving to the suburbs of Charleston, South Carolina, knowing no one, with a wife and two toddlers and a Wisconsin accent, he comes across as a little manic and dishevelled. His work around that time is quite impressive in detail, ambition and imagination no matter what world you come from. In 2018 he is not purely modelling his images per se, but integrating readymade models that he buys in online storehouses like TurboSquid, into these visionary landscapes that, if you were into this thing, you can imagine being inspired by the skill and fullness of his realised fantasies – Ben Davis, in his journalistic zeal to dig the dirt is wrong to see no value here at all. If you go back to 2013, what Winkleman describes as the abstract period of his work, but is really the anatomic and cellular micro-version of what would become the macro-vision later, you see an artist assembling the building blocks to his future world. Yes, his style has changed over the last decade, not because he “gets bored with one style” as he says, but because technology and his skill at rendering and taking shortcuts has evolved. But as Ben Davis underscores, the tone of Beeple’s hick message was set very early on. So getting better at this thing has been the only obstacle to Beeple getting bigger, more hedonistic, abject and, anything goes – the postmodern trope that speaks the language of his critics. Art school awaits.

BEEPLE, SHUT THIS MF UP (VOTE)”, EVERYDAYS, 3 NOVEMBER, 2020

The anything goes of Winkleman's more recent work, what he calls his “weird period”, is a digital microcosm swelling and weeping with lactating and desiccated politicians in an orgy of technology: Blame the Trump administration. It's an abject fantasy with evolutionary ambitions to pick up its own glutinous body, walk and talk – to be real. I can imagine kids being mesmerised and elated by Beeple's landscapes, inspired even to do what he does. In a direct text to Winkleman, the so-called enfant terrible of the traditional artworld – Damien Hirst – gave a nod of appreciation to the enfant terrible? of the crypto-artworld: “My fifteen-year-old son showed me your work a while ago, this is fucking great, congratulations, you’re awesome.” I can see my eight-year old son picking up a pencil after witnessing Beeple's images. This is not speculative, like the bubble in cryptocurrency, this is the truth. But would I show my son his recent images – the images that Christie’s particularise in their promotion? My son would probably just laugh first and then start to slowly upload the fascinating details, details that would get stretched, contorted and embedded in his brain, to become a worse version of what he just witnessed. This is what we do with images. We process them with other images. We relate and contrast one image with the next. We file them away; versions that fade or corrupt over time. We now can look them up to refresh those faded and corrupted images, but they never look the same way as we remember, they have changed, we have changed, the world has changed, everything has changed. Experience and our ability to skim and digest images gets easier and lazier with time and exposure. Like a kid, Winkleman wants to make a new image, today and every day that he has never seen before – to rediscover that wonder, that shock to the neurons, that will reset everything to zero and start again, to salivate again, to babble again. What does Winkleman's brain look like after 14 years of doing this thing, creating and uploading these images for the sole purpose of “getting better” and seeing something new and “fucking cooler” than before? Look for yourself.

BEEPLE, “MOMA $HIT”, 17 FEBRUARY, 2021

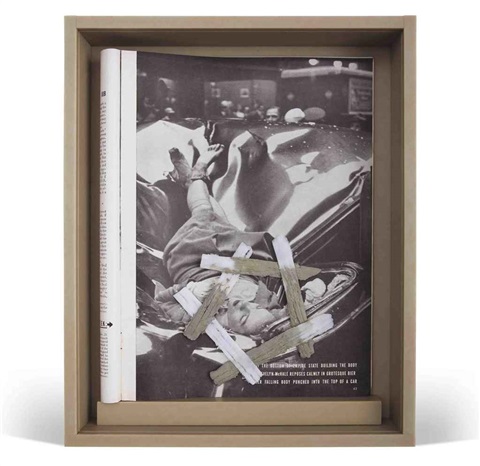

Beeple-bombed, critics have never ever been in such concord. House styles have become homogeneous over the issue. Entertaining? yes. Fascinating? Absolutely. Critics are pumped like never before, aggressively defending the traditional artworld while continually critiquing Beeple from the position of art history, something that Winkleman has no truck with, is as absurd as some of his digital topographies. The wrong questions are being asked by the wrong people. In the trenches, art is not subjective, it is communitarian in the worst way. The community, not the artist, dictates and defines what art is. Winkleman said somewhere that he wants to do an art history course next, something that he has become interested in because the critics won't shut up naming all these artists from history that Winkleman has never heard of (except for Jeff Koons and Kaws, who are also unacceptable to the artworld… oh… and he recently tipped his cap to banana man Maurizio Cattelan [above]). The critics have piqued his interest in history when all Winkleman was interested in was the present. As Smee writes in his offensive on Winkleman, and in defence of the artworld's historical innovation in respect to its casual embrace of the incorporeal object of ideas in the face of the emergence of NFTs: “The art world is used to assigning value to ideas. In fact, a whole genre of art — conceptual art — gives primacy to ideas over whatever actual forms they may take.” But Smee is missing a beat here, in that ‘the idea’ is always entangled in ‘the form’, the form speaks to the idea and the idea speaks to the form. Smee continues, the “conceptualists... thought that if you dematerialized art — if you took away the object and our urge to fetishize it — it would be an act of resistance against the art market and the whole capitalist system”. What's different, in Smee's opinion, is that NFTs are a way to commodify and festishise everything, even if the fetish is not an object that you can hold in your hands, “inscribing a new chapter in the annals of frictionless capitalism”.

[TODAY 30 MARCH 2021]

Winkleman – pawing one of his works encased in a digital frame during a podcast – is quick to say he is in no way a cryptocurrency purist. He immediately converted his hard wallet of Ether into cash money following Christie's auction. Holding the digital frame while talking, he says the frame is a way to help people, not only hold their NFT artwork in their hands, but to transition them into thinking about digital art as an object (in so many words). NFTs are in their Minecraft infancy. Winkleman’s digital frame conceit once again sounds a lot like Winnicott and his “Transitional Object”, the object that helps the infant transition from the mother into the world. In this case, the frame is the dodie for transitioning into the digital world. Commodity fetishism has not died with the NFT, it has just taken a new form, one that, in the Freudian sense of the fetish, is equally if not more wrapped up in inflated desire and power. The desired or denied object is always displaced, out of reach, but, in its atomised or bit-part form, promises to become more than the image beyond the screen. And can we say Metakoven, the buyer of the work, is a cryptocurrency purist, a digital fetishist, anti-establishment, communitarian, gambler, or just another opportunist who loves money, things, ownership, legacy, power. We all have our thing for things. Especially art things, wherein lies an illogical exchange in value and satisfaction. “No fetishist ever loved an old shoe more than an art lover loved a work of art.” (George Bataille) Perhaps ‘ownership’ here is the festishised object, ownership being elusive in its digital form, and desired more for that reason. Digital ownership is the evolution of the festishised object. And as Winkleman says, “Having some sense of ownership over their digital selves [and the things we take with us]” is everything these days. But perhaps this is off brand, the way Winkleman’s first proposed lot for auction was off “brand” for Christie’s, who then disguised and diffused the off “brand” within the ‘on brand’ mosaic jpeg.

Modern art has always flipped the coin in terms of chance and form, but the coin has always landed on its rim so heads and tails are made visible. If we agree from the perspective of the “traditional” artworld that Winkleman’s work is not art, then perhaps, as an embodiment of society, Beeple, Winkleman, the auction, the reaction, is the art? If we think in these terms, with the coin resting on its rim, this is art with capital A. So if we flip the coin on Beeple's future: Winkleman goes to art school, gets all self-conscious, discovers irony and context as a way towards traditional art acceptance. Ben, Sebastian, Jerry, Jason et al are happy. Beeple is not. The end.

JOHN GERRAD, SOLAR RESERVE, 2014, SIMULATION, EVA INTERNATIONAL, 2018, PHOTO: OISIN MCHUGH

What does this all mean for the experience of art if we all become digital festishists in the future to inhabit virtual galleries to the disavowal of the physical? (Sometimes when I see my son play Minecraft I visualise his limbs spider-contorting and disappearing into the screen forever.) Some of my most memorable experiences of “traditional” art on this island and others – New York, Venice – have been the architectural simulations of John Gerrard, who has made two NFT drops, one in 2019 and the second in March 2021, the latter being the first “superneutral” NFT in the marketplace (“energy usage associated with the auction” will be offset by a regenerative farm founded by Gerrard also in March 2021). All the negativity surrounding Christie's auction and Beeple has distracted from what NFTs mean for digital artists (the resale commission of 10% for artists is something that doesn't happen in the art market proper/ transparency in trading/ and ownership can be easily divided and traded). Further, digital artists have, up to now, been forced to formulate and innovate “physicals” for the commercial market to make a living. We are now dealing in two worlds. It states in the press release for Gerrard's current NFT drop, Western Flag, “This project returns Western Flag to the digital community that made it famous.” Two communities and their separation is being unconsciously inferred in this statement in the strict sense of segregation, whereby ‘community’ is not being idealised as an holistic idea but a designation, an identity. And there is a lot of them vs us rhetoric surrounding Beeple: traditional artworld vs crypto-artworld, digital vs real, objects vs jpegs. And it is true, digital art has always had a glitchy labour into the physical world with a dependency on what device is available at any given time and place. But that glitchiness between contrasting forms is what artists utilise best in the relationship between human and digital, subject and object, things and thoughts, sensory and sense-making. Art, at its best, is awkward. Art in the truest sense is a toddler falling and getting back up. Beeple is a toddler in free fall.

![[TODAY 30 MARCH 2021]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1617087899994-4EBLBSEZQAN344VKUZMB/Screen+Shot+2021-03-30+at+08.01.32.png)

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)